On 15−17 March, Russia will hold another presidential ‘election’. In preparation for these elections, the Russian authorities have been trying to keep Russian citizens as far away as possible from the possibility of participating in governing their own country. Despite claims that society has supposedly rallied around the president, the real situation on the ground does not look so rosy for the Kremlin. Over the past year we have seen a military mutiny led by Yevgeny Prigozhin, protests by the wives and mothers of those mobilised for the war against Ukraine, queues in support of the nomination of the previously rather obscure politician Boris Nadezhdin that functioned as kind of anti-war demonstrations in a country where demonstrations of any kind are banned, crowds flocking to Alexei Navalny’s funeral, and local protests and riots in various parts of the country, including Bashkortostan, Yakutia and Dagestan. In September, we saw the authorities facing the very real threat of competitive election campaigns — in Khakassia, a ‘United Russia’ party candidate withdrew from the gubernatorial election a few days before the voting began for fear of losing. It also became clear that anti-war rhetoric is popular at the polls — even the half-dead «Yabloko» party managed to secure seats on local councils in two election campaigns, with decent results (7% and 9%).

Against this background, the measures taken by the authorities to shield themselves from society look quite logical. Compared to its 2018 version, the law «On the Election of the President of the Russian Federation» has undergone a significant transformation: amandments affected two-thirds of its articles. Opportunities for election monitoring have been seriously curbed, registration rules have been tightened, and non-transparent and therefore easily falsifiable methods of voting have emerged — the remote electronic voting and multi-day voting.

The trimming down of the campaign

In his fifth presidential election, Putin ran against the smallest number of candidates ever (but the drop-out rate of the presidential hopefuls was the highest since 2012). Only once before, in 2008, when Dmitry Medvedev won, have there been four candidates in a presidential election. But then his rivals were the main political «heavyweights» of the time: Gennady Zyuganov and Vladimir Zhirinovsky. Now the incumbent president’s rivals do not enjoy any popular support whatsoever. Many people still confuse Leonid Slutsky with the football coach of the same name. Nikolai Kharitonov has not been seen doing anything remotely remarkable since his last attempt to run for office 20 years ago, and Vladislav Davankov is a complete political novice.

At the same time, in the past, representatives of the conventional «liberal», «pro-Western» camp of Russian politics have always participated in presidential elections: just think of Grigory Yavlinsky (2000), Irina Khakamada (2004), Mikhail Prokhorov (2012) or Ksenia Sobchak (2018). This time the authorities even decided to refuse registration to Boris Nadezhdin, who was hardly less obscure at the start of the campaign than Vladislav Davankov, but who, too, is very much part of the «system» albeit with much more experience in public politics. The inexperienced ‘dark horse’ Yekaterina Duntsova was not allowed to register as a presidential candidate either.

It looked as if the owner of a Ferrari was afraid to compete with the driver of a Soviet Zhiguli. In reality, this means that either the former does not own a Ferrari or the latter does not own a Zhiguli.

Gradually, the situation became even more revealing. The election campaign started shrinking in size. There were many actors involved in trimming the campaign down: the authorities and election commissions, the media and the candidates themselves. The «Golos» movement reports that, according to its long-term observers, the candidates’ campaigns are almost invisible in the regions, and even Putin’s campaign is less dynamic than it was six years ago. Voters find out about visits by candidates or their deputies only after they have left the locale. A likely reason for this could be that candidates do not want to repeat the fate of Pavel Grudinin or Sergei Furgal who were both part of Russia’s «systemic politics» but [with their suddenly surging popularity] unwittingly caused problems for the Kremlin in the elections.

The media, including the regional ones, are not writing about the candidates. For example, federal TV channels have reduced the amount of coverage devoted to the elections by 1.6 times compared to 2018. Just two weeks before the elections, they were mentioned in less than half of the news programmes on six central TV channels. Journalists from the country’s surviving independent regional media admit that they also try to avoid the topic of elections, just in case. The incumbent head of state is mentioned seven times more often on TV than the other three candidates combined.

Relying on coercion and falsification

People do not notice these elections. There are only two ways to achieve a 70−80 per cent turnout in such conditions — administrative coercion and falsification. To do this, the authorities have to «trim down» the campaign. But this only happens when the authorities fear a large protest vote. In this case, everything is done to prevent dissatisfied voters from mobilising and going to the polls.

Instead, they have to bring «their own» kind of people, those they trust. This is why the current election campaign is more administrative and coercive in character than the previous one from six years ago. It is not only state employees who are under pressure, but also people working in private campaigns, even those with no close links to the state. This is helped by the introduction of the electronic voting and the multi-day voting: Friday as the first day of voting has proved very convenient for bosses in terms of their ability to control their subordinates, especially when voting can be done online (in which case you can simply stand behind your employees at the time of voting).

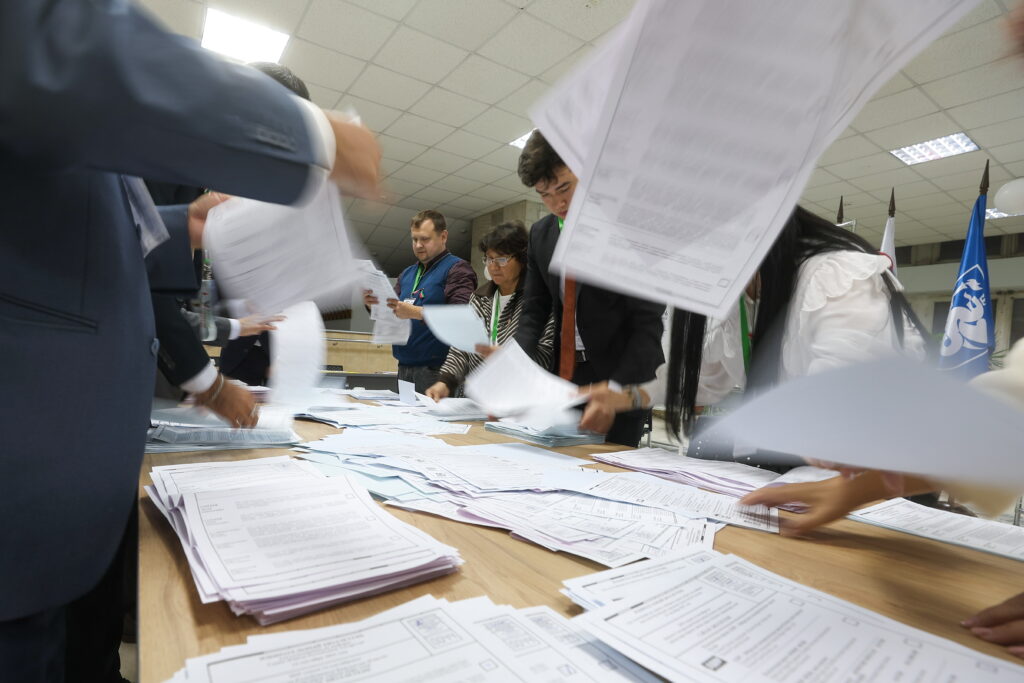

In the days leading up to the vote, preparations were made for massive rigging.

Monitoring on polling days, which has already become extremely difficult at the legislative level, is now simply being disrupted. Watchdog associations and individual observers report that agreements with candidate and party headquarters to send volunteers to polling stations are being cancelled at the last minute. People in unofficial parties say they are under pressure — from the authorities and even the election commissions. Even «Yabloko», in at least one region, has banned its commission members from sharing information with observer associations. This time there will be no web cameras allowing observers to monitor the procedure either. Putin’s 2012 suggestion to install webcams at polling stations so that every citizen could log into any polling station from home and make sure that everything was normal there has degenerated to the point where even candidates do not have normal access to such broadcasts.

Under such conditions, the authorities can whip up any desired result, especially since it is not difficult at all. Putin needs 55−60 million votes to get the result he needs. At the same time, the authorities have two groups of votes that are absolutely opaque and beyond the control of society. It seems that about 10 million voters will use the remote e-voting system, and another 20−25 million of votes can be collected in «electoral sultanates» like Chechnya or Kuzbass, where the results are simply forged. To be sure, there will be falsifications in other regions as well.

Despite their closed nature, the current elections provide a lot of information for reflection on the real state of society, or at least on the Kremlin’s fears of it: those who do not believe in the possibility of democracy in Russia should take their faith from Vladimir Putin, because he certainly fears democracy and is trying his best to prevent it.