Since the summer fighting season, Russia has achieved significant tactical gains along the line of contact, yet there is no evidence of a major operational or strategic breakthrough. Russia cannot accomplish its strategic goal of subjugating Ukraine in 2026 absent a major collapse in Ukrainian defensive lines. The current Russian strategy appears to rest on three primary pillars. The first is the destruction of Ukraine’s civilian infrastructure to inflict pain on the population for as long as it continues to resist. The second is attriting the Ukrainian armed forces so that they cannot defend the entire front effectively. The third is seizing the territorial boundaries of the Ukrainian oblasts that Putin declared part of Russia in 2022; capturing these territories would allow Putin to more easily present a war-ending agreement as a form of victory to his domestic audience.

In pursuit of the first pillar, Russia has markedly increased the use of Shahed-pattern drones, which feature in nearly daily air attacks. These strikes have crippled Ukraine’s power infrastructure, causing major blackouts across eastern and central Ukraine. In Kyiv, the situation is among the worst of the entire war, with more than half residents enduring intermittent absences of water, heat, and electricity for days. Given the substantial resources allocated to this strike campaign against Ukraine’s infrastructure, Russia appears heavily focused on eroding societal cohesion and the population’s willingness to fight—potentially to the point where Ukrainian society and elites would accept, if not full capitulation, then at least an agreement broadly favorable to Russia.

In the background, the Russian army continues its war of attrition, concentrated on the so-called «new territories.» Over the past few months, this effort has proven successful in Donetsk and Zaporizhia Oblasts but less so in Kharkiv Oblast. Russian forces have captured territory consistent with much of the summer 2025 fighting season, albeit at ever-increasing personnel costs.

Exhaustion in Ukrainian society is evident in conversations with those still in Ukraine, as well as in statements and acknowledgments from Ukrainian leadership. Much of Zelensky’s New Year’s address to the nation was devoted to recognizing the ongoing trauma felt by Ukraine’s population while insisting that the country must continue fighting to secure an agreement beneficial to Ukraine. The framing Zelensky chose for this national audience in the opening minutes of the address was direct: «Are we exhausted? Extremely. Does that mean we are willing to surrender? Those who think so are extremely mistaken.» Here, Zelensky both guides and provides a frame of understanding for his mass audience of constituents while simultaneously signaling to Moscow that the current strategy of bombing Ukraine into submission is not a viable path to victory for Russia.

The Bombing Campaign Intensifies

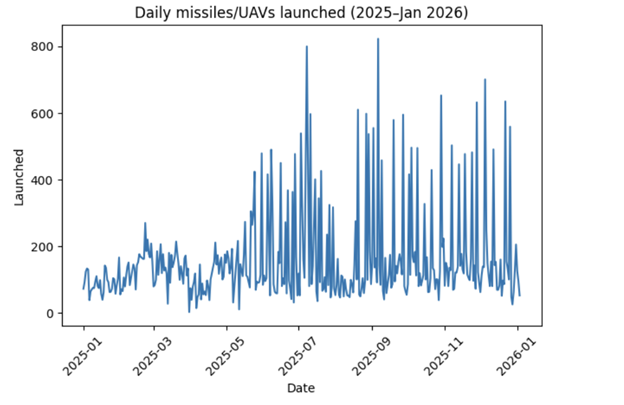

Publicly available reported launch data indicate that the intensity and scope of aerial attacks on Ukraine have continued at an expanded and intense pace since May 2025, with only a brief lull in mid-summer 2025. The most significant trend is that daily salvoes have consistently grown larger. July 9 and September 7 saw strikes of record intensity, with some daily attacks involving over 740 and 800 munitions, respectively. The September strike achieved a rare successful hit on government buildings in central Kyiv.

Russia’s bombing campaign has proven more effective than in previous winters. Blackouts have been generally more extensive, particularly in oblast capitals closer to the front. Ukraine’s energy ministry—operating amid a massive corruption scandal involving millions of dollars—is implementing controlled outages across all oblasts to conserve and allocate resources. Unprecedented blackouts have already occurred in Dnipro city and Zaporizhia.

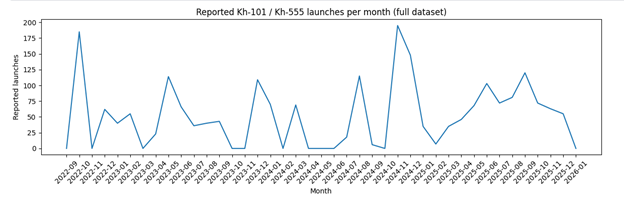

Ukraine’s June operation targeting Russia’s bomber fleet at strategic bases across four different oblasts was a major effort that damaged at least 40 aircraft and completely destroyed at least 10. Among the destroyed and damaged aircraft were at least 15 Tu-95s and 12 Tu-22s. Ukraine targeted these aircraft and airfields because they serve as the primary launch platforms for the Kh-101/Kh-555 family of cruise missiles. The Kh-101/Kh-555 are non-nuclear variants of a nuclear-armed cruise missile and can only be launched by large strategic bombers such as the Tu-95, Tu-22, and similar Tupolev designs built for heavier payloads. These missiles pose a particular problem for Ukraine, as they can damage and destroy targets that Shahed-pattern drones simply cannot reach due to the greater weight of munitions carried.

However, data on reported launches show that after the June attacks, Russia experienced no decrease in usage and even reached previous milestones for the number of Kh-101/Kh-555 systems launched per month. September 2025, with 120 reported launches, was comparable to the 115 launches in August 2024. While good open-source data on salvoes in the first six to seven months of the war are unavailable, Russia peaked in usage of these systems at 195 reported launches in November 2024 and 185 in October 2022. At present, the remaining aircraft stock can continue to threaten Ukraine, although further strikes and overuse of the surviving fleet could begin to impact operational tempo over time.

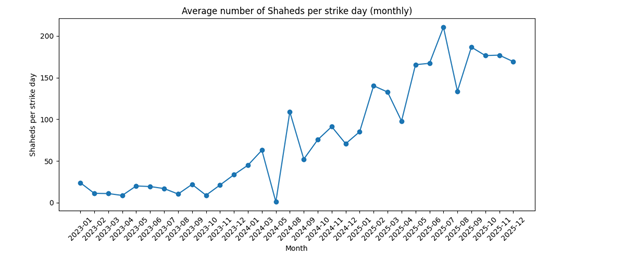

Traditional cruise missiles have overall taken a backseat in operational use to Shahed-pattern systems. Attacks using Shahed-pattern drones are now a near-daily occurrence. Russia is expanding both production sites and operational tempo. Throughout 2023, the average number of Shaheds in a daily strike was less than 50. In 2024, averages crept closer to 100. Since May 2025, the average has reached upwards of 150 per strike, with June 2025 seeing averages exceed 200 per day. While these are averages, the trend clearly demonstrates that Russia can field greater quantities of these munitions in ever-larger salvoes.

In tandem, the conceptual line between the Shahed as a «kamikaze drone» versus a cheaper cruise missile is increasingly blurred. The design is now being iterated upon to resemble a cruise missile more closely in both form and function, with some models now featuring turbojet engines. Leaks from Ukrainian intelligence in recent months have included mock-ups of Soviet-era Su-25s serving as launch platforms for a new generation of Shaheds. While the engines on experimental Shaheds shown in public releases are smaller, commercially available Chinese engines rather than those manufactured by the United Engine Corporation, they can be produced with fewer technical hurdles than more complex systems. This scale is essential for Russia to overcome Ukraine’s sophisticated, multi-layered air defenses, which rank among the most formidable in the world by necessity.

Russia has even returned to using Putin’s Oreshnik missile, which experts suspect is a non-nuclear evolution of Russia’s nuclear ballistic missiles. This marks only the second use of the weapon. Ukrainian officials claim the missile was not fully equipped with warheads. Russia asserts the target was the Soviet-era Lviv State Aviation Repair Plant; preliminary open-source reports suggest this may have been accurate and would align with the previous use of the missile against Pivdenmash. It remains unclear why Russia would forgo a full payload. While useful for signaling, the system possesses real destructive capacity given its ability to carry more explosives than other missiles in Russia’s conventional arsenal. Unlike other more unwieldy weapons paraded by Russian leadership in domestic and international propaganda, it has genuine military applications. American military thinkers have explored similar systems for airfield attacks since the 1960s. Advances in guidance technology make such applications more feasible on paper than they were 60 years ago. For whatever reason, Russia has not yet used the system against major government buildings in Kyiv, but this remains a viable option should Russian military leadership choose to pursue it.

It is difficult to quantify the psychological impact of this intensified bombing campaign on Ukraine’s population, but the Kremlin appears to bet that it can break Ukrainian society’s will to resist. Bombing electricity and heating infrastructure alone will not collapse the Ukrainian frontline, but the strategic logic holds that a demoralized and traumatized population may be more inclined to accept a settlement that Russian leadership can portray as a victory to both domestic and international audiences.

Tactical and Operational Developments

Since September, Russia has made significant tactical advances in Donetsk and Zaporizhia Oblasts but continues to fall short of operational or strategic breakthroughs. In January, the battle for control of Donetsk Oblast had already lasted longer than the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union and the subsequent capitulation in Berlin. The Russian army continues to make slow progress at high human and financial costs.

The most high-profile fighting in autumn and early winter centered on the small city of Pokrovsk and its surrounding areas. Russia had been attempting to seize the city for upwards of a year. Russian forces initially intensified activity in Pokrovsk’s southwestern neighborhoods. By October, up to a third of all fighting along the front was reported in Pokrovsk. By October 20, Ukrainian units reported that Russian infiltration teams had reached the center of Pokrovsk. This tactic—enabled in part by how thinly spread Ukrainian troops were—became a major theme of Russia’s 2025 offensive operations. Given the fog of war and conflicting claims, pinpointing the exact day Russian forces fully took control of the city is difficult; however, by December, Russians had reached the center in force.

In terms of raw territorial gains, Russia also made major progress by capturing small villages in Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhia Oblasts, though these advances were more pronounced than around Pokrovsk. These villages, in isolation, lack significant strategic or operational value compared to other points near the fighting. The N15 highway, connecting Zaporizhia to Donetsk city, has seen limited gains, with Russian forces failing to capture the village of Iskra/Andriivka-Klevtsove, which provides a direct river crossing into Dnipropetrovsk Oblast along the N15.

Instead of pursuing a direct route to Zaporizhia, Russian forces achieved the most success in operations farther south of the highway. From September 1, 2025, to mid-January 2026, Russian forces pushed forward approximately 25 kilometers deep into isolated villages along an axis roughly 30 kilometers wide. The town of Huliaipole has become the center of gravity for this line of advance. Russian forces have faced territorial defense units from the 102nd and 106th Brigades here, while more high-profile units remain focused on the line from Donbas to the Russian border. Ukrainian commentators note that Russia is adapting to Ukrainian weaknesses in this sector, employing slightly larger squad-sized groupings. Where Russian assault groups previously consisted of two to three soldiers, they now use five to six in some places.

Russian forces in Zaporizhia were active to a lesser but still significant extent in the far west of the oblast. In December and January, the towns of Stepnohirsk and Primorske came under increasing attack. These two towns—firmly on the Ukrainian side of the lines since 2022—lie about 25 kilometers from Zaporizhia city proper. Natural obstacles, including the Konka River (a tributary of the Dnieper), remain before Russian troops can threaten the oblast capital. Nevertheless, given the short distance, any towns and villages along this axis place more of the city under threat of direct fire.

Farther north, Ukraine’s 2nd Corps—built around the Kharkiv National Guard brigade Khartia—launched a successful counterstrike in Kharkiv Oblast near Kupyansk in December. Ukrainian forces focused on seizing forested heights to the northwest of Kupyansk and pushing back into the city. Soldiers from the unit claim that Russian forces in Kupyansk lack overland lines of communication across the river and, mirroring the Kursk operation, have instead used gas infrastructure near the village of Holubivka to infiltrate Kupyansk and sustain themselves.

While this may be accurate, Russian forces maintain greater control over villages and crossing points on the Oskil River than they did at the beginning of 2025. Although the effectiveness of these crossings for supply is unclear due to the constant drone threat, Russian forces captured river crossings north of Kupyansk in January 2025. Ukrainian sources admit that Russia has held the town of Dvorichna—located about 8 kilometers from forested areas and villages Ukraine has retaken—since June 2025. Russian troops expanded control over some villages along the Belgorod Oblast-Kharkiv Oblast border in October and November 2025. This process of seizing small villages and towns in northwestern Kharkiv Oblast has been very slow but serves as a base for potential future advances by Russian troops in Kharkiv Oblast.

Russia held nominal control of all these areas up to the Siverskyi Donets River in 2022. If Russian forces were to repeat their methodology from Donetsk and Zaporizhia, they would need to advance another 40−60 kilometers west from their current positions along a roughly 45-kilometer frontage to retake just the villages and towns north of the highway connecting Kupyansk to Kharkiv. The more strategic move of pushing south to Izium and cutting off Ukrainian forces in Donetsk Oblast—which Russia attempted but failed to achieve in early 2022—would require retaking the territory recently lost in Kupyansk and advancing another 60 kilometers south. Given the slow rate of advance, linking the Kupyansk operation with Russia’s broader operational goals in Donbas is simply not feasible in 2026. The best Russian forces can hope for here is tying up Ukrainian units and organizational focus from other parts of the front where Russia can make progress.

Russian forces made tactical gains in the autumn and winter fighting season along the border of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts. In December, Russian forces captured the town of Siversk, which had eluded Russian control for years of fighting. The Ukrainian commanders in the 10th and 54th Brigades responsible for this section of the front were later sacked amid accusations of falsifying reports on which positions Ukraine actually controlled. Mismanagement in the Ukrainian army remains a major issue but is offset by even worse mismanagement on the Russian side. Since taking Siversk, Russian forces have established a base for further advances and have slowly pushed west across small villages between Siversk and toward Sloviansk.

A battle for Kramatorsk and Sloviansk—the veritable stronghold cities of Donetsk region—remains on the horizon and could be months or up to a year away, depending on how many forces each side commits to this part of the front. Even the most optimistic pro-war commentators note that dozens of kilometers of fighting remain before a battle for Donetsk region can be called complete. Without a collapse of Ukrainian lines, tens to hundreds of thousands more casualties will likely be required to achieve these objectives using the Russian army’s current infantry-first approach. This approach allows the Russian army to conserve tanks and other armored vehicles for future operations where they are absolutely necessary.

Looking Forward

As the war approaches its fifth year, both sides are deeply stretched but retain the capacity to continue fighting. Russia will continue to rely on demoralizing and terrorizing Ukraine’s civilian population as long as funding and available aircraft permit. Actual predictions for frontline progress remain unclear, but previous choices by both sides and strategic realities can provide guidance.

On the battlefield, it is clearest that after Pokrovsk, the remaining major population centers in Donetsk will be a primary goal for the Russian army. At the current trajectory, Russia could capture a significant portion of Donetsk Oblast by year’s end if Ukrainian forces become too thinly spread. Russia launched a failed May offensive in 2024 to seize northern Kharkiv Oblast. Similar efforts to march on Sumy Oblast using Russia’s most highly regarded formations likewise failed in 2025. Russian army leadership will need to decide in the coming months how much manpower and materiel to allocate to theaters beyond Donbas.

Both in Kursk and Kupyansk, the Ukrainian army has demonstrated that it too can launch offensives, seize territory, and exploit weakened Russian units. Ukraine will need to decide where to allocate its most capable forces. As seen in Huliaipole and Siversk, poorly managed army units and territorial defense forces can hold only so long. At present, Russian advances are so slow and inefficient that this can be tolerated. It is almost certain that Ukrainian leadership will continue their strategy of identifying weak points in Russian lines and striking there for maximum political effect.

There are no indications that either side is exhausted enough to accept peace. Ukraine, with good cause, fears abandonment and a future invasion. Putin, facing the worst crisis of his 26-year rule, is not prepared to admit defeat and confront the instability that losing the war could unleash in Russian society. Unless a major strategic breakthrough occurs on either side, the fighting is on track to continue—or even intensify—into 2027.