Hundreds of thousands of Russians left Russia after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. This is the biggest wave of emigration since the dissolution of the USSR. Many migrants represent the IT sector. This exodus of a highly skilled workforce will inevitably lead to an outflow of competent specialists from Russia.

After the outbreak of hostilities, tens of thousands of Russians went to Turkey, Armenia and Georgia, countries that do not require a visa to enter. Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were the most popular transit countries in the absence of direct flights to EU countries. This scale of migration has a number of implications for both Russia and the host countries. Unlike previous waves of migration, this one comprises politically active individuals who have the potential to self-organise and form alternative political networks that cannot operate in Russia at the moment.

Will the new migrants form alternative civic associations, or will they choose to sever ties with their homeland and start from scratch? This may not seem like the most important question, but political migrants and diasporas in history have sometimes played a crucial role in consolidating democracies. Some have even led or been part of new democratic governments. For example, Valdas Adamkus, president of Lithuania, and Lennart Meri, the first president of Estonia, were in exile for a long time. Finally, most of the new migrants are people who are active in the public space and are able to keep in touch with those who stayed in Russia and do not have opportunities to make their voices heard.

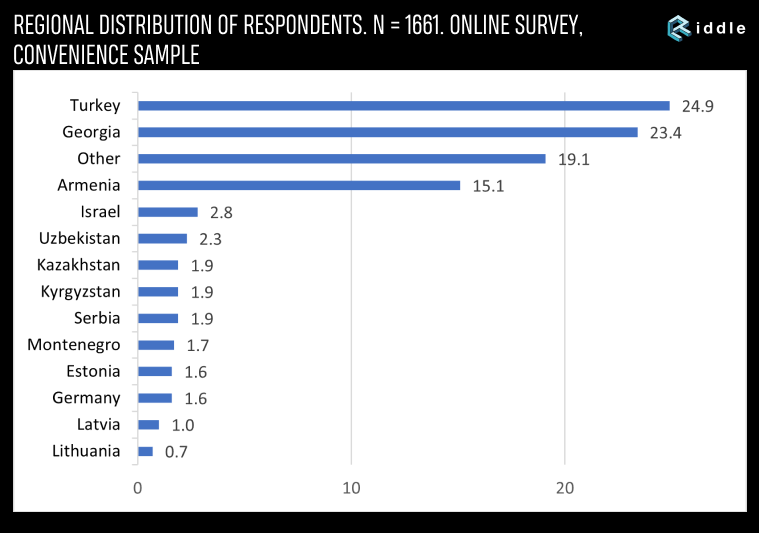

A team of sociologists from OK Russians conducted several surveys on Russian emigration and found that the majority of migrants settled in Turkey (24.9%), Georgia (23.4%) and Armenia (15.1%). Following the outbreak of the war, Israel greatly simplified its repatriation rules for Ukrainian and Russian Jews in March 2022. About 2.8% of respondents moved to Israel. Slightly smaller numbers of migrants arrived in Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan — about 2% of all respondents. The most popular European destination countries were Serbia (1.9%), Montenegro (1.7%), Estonia (1.6%), Germany (1.6%) and Spain (1.5%) (see Figure 1). The choice of countries was largely random and depended on the availability of tickets and the rules for entry and stay. This was noted by 58% of respondents. Less than half of the sample plan to stay in these countries (43%). A quarter plan to move on (18%), 35% felt confused at the time of the survey, and as few as 3% plan to return to Russia. In other words, many moved to countries where standards of democracy are not necessarily observed, but at the moment they look safer than Russia.

Back in March, President Putin labelled those leaving Russia ‘a fifth column‘ and said that the Russian people would ‘always be able to distinguish true patriots from bastards and traitors’, and that the people would simply ‘spit [the latter] out like a fly that accidentally flew into their mouths’. He added that emigration was ‘a natural and necessary self-cleansing of society‘. Alas, this is the opinion not only of those who support the government’s policy but also of some opposition-minded citizens who have stayed in Russia. Now and then squabbles over who are the real patriots or the true opposition make headlines. However, arguments about whose moral choices are better are precisely what prevents coordination and cooperation between those who stayed in Russia and those who left. Those who are outside Russia have the ability to openly disseminate information, provide assistance, form civic associations and build working relationships with the leaders of the host countries. Those who stayed in Russia are not out of touch with the reality inside the country and continue to resist. Maintaining family and friendship ties between those who stayed and those who left, as well as relationships for the sake of civic and political activity, is an important prerequisite for building an alternative political agenda for Russia.

Many countries have large numbers of long-settled Russian migrants whose political views may differ greatly from the views of those who have just arrived. Russian-speaking diasporas have often been used by Russian authorities as tools of ‘soft influence’ on a par with media propaganda and cyber tools in the form of bots, trolls and hacker attacks. Russia’s state policy with regard to compatriots living abroad, the Russkiy Mir Foundation, Rossotrudnichestvo and the World Coordinating Council of Russian Compatriots Living Abroad attempt to establish channels of state influence on the Russian-speaking population abroad. However, international sanctions and the boycotting of Russian organisations will undermine Russia’s attempts to exert any influence abroad. In any case, it is believed that traditional Russian migrants tend to favour more conservative political parties and regularly publicly express support for the Russian leadership. For instance, the anniversary of the victory in the Great Patriotic War this spring raised many controversies: some organised patriotic car rallies, while others joined rallies in support of Ukraine or organised days of mourning. The organisers of these events feared clashes and possible provocations.

The new migrants are worlds apart from the traditional Russian migrants in terms of political views: they are politically mindful, show solidarity with each other, are in touch with those who stayed in Russia and have typical middle-class characteristics. Only 1.5% of the new migrants interviewed voted for United Russia (as compared with over 50% of respondents participating in the Levada poll), while 86.4% followed the recommendations of ‘smart voting’ (8% according to Levada). New migrants are much younger and on average much better off financially. About half are involved in the IT industry, and the vast majority speak English. Among those who were employed, 45% worked in the IT industry, 16% worked in the arts and culture sector, 16% were managers, 14% were accountants and teachers, and 8% worked as journalists. The main reasons why respondents left their jobs in Russia include the depreciation of the rouble and the country’s economic inefficiency, an unwillingness to pay taxes in Russia and thus sponsor the war as well as job changes planned in advance. Given extreme politicisation, tensions between different groups of the Russian-speaking population in their host countries cannot be ruled out. Finally, new migrants are much more capable of self-organisation and forming self-help groups. The level of mutual trust among the new wave of migrants is very high.

It is important to understand that this does not mean that all ‘good Russians’ have left their homeland. First and foremost, those who had financial and career opportunities did. The proportion of Russians who are against the war but stayed in the country, according to various estimates, is between a quarter and a third of the population. The majority of new migrants are IT workers and private entrepreneurs. Activists, academics, journalists and employees in the non-commercial sector account for a small proportion of them. Many have stayed in the country. The most privileged left. Those at risk of criminal prosecution make up about a quarter of respondents. And this is not a small number. Thus, there are Russians who are against the war on both sides of the border, and maintaining solidarity and ties between them is a key task in the current situation.

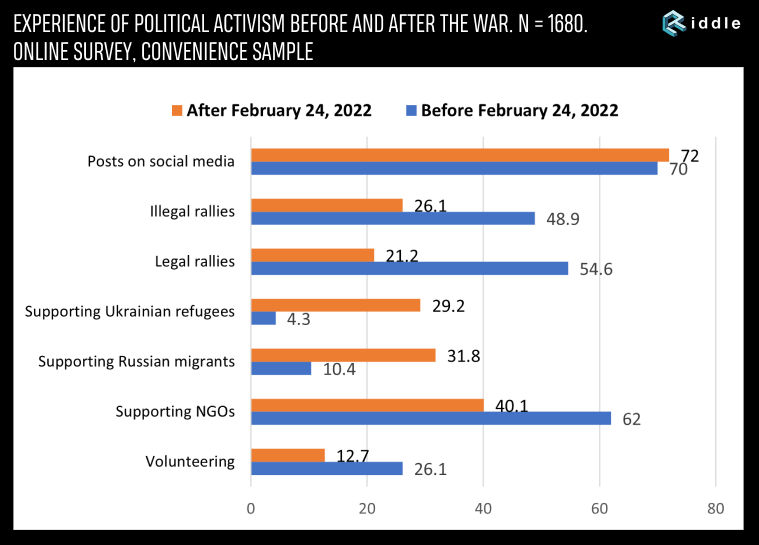

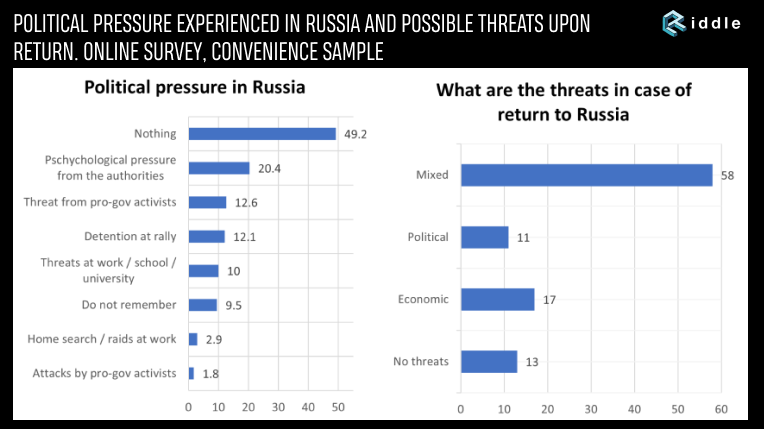

One might assume that the lion’s share of those who have left are primarily economic migrants, mainly entrepreneurs and software developers, which has nothing to do with their political views. However, the data suggests otherwise. The vast majority of respondents are interested in politics and have experience with active political participation. Over 70% were active on social media and had signed anti-war petitions; about half had participated in illegal rallies (48.9%) before the war; and 26%, after its outbreak; 29.2% actively supported Ukrainian refugees; and 31.8%, Russian emigrants; 62% had supported non-profit organisations before the war; and 40%, after its outbreak. Many of those who left pointed to political pressure before departure: pressure at work in the form of ‘preventive counselling’, warnings and conversations with management, less frequently threats from pro-government activists, detentions and searches. Half of the respondents fear persecution for posting and disseminating information about the war in Ukraine on social media, 20% are afraid of conscription, 19% are afraid of losing access to life-saving medicines, and 9% are afraid of criminal prosecution.

The majority of migrants have a gloomy vision of the near future: 72% believe that their living conditions will deteriorate, 70% do not believe that the political situation will improve, and 72% fear discrimination against Russian citizens abroad (but only a quarter have really faced discrimination). One way or another, many migrants feel lost and miserable and do not feel entitled to claim certain rights, not to mention privileges compared with refugees from Ukraine. For this reason, they mostly rely on their own resources and networks which they formed immediately upon arrival in their host country. International sanctions have obviously also affected those who left the country immediately after the outbreak of the war. Migrants have no access to their savings, and there are restrictions on remittances. Economic expectations are also rather pessimistic: 30% will not be able to provide for their families in the coming months; about half expect working conditions to deteriorate. Software developers feel more confident about the future, while healthcare workers feel most vulnerable.

Either way, the new wave of migrants, despite their vulnerability, have a number of important assets that could potentially prove useful for anti-war and pro-democratic movements. Several organisations have already announced a number of initiatives to help opposition-minded Russians adapt to the new conditions. One of the most sensational was the proposal to introduce passports for ‘good Russians’, voiced at the Free Russia Forum, which would allow those who leave Russia and do not support the war to avoid sanctions abroad. Despite the extremely unfortunate format of the initiative’s presentation, the idea might have had some chance of success had the initiators not made the grave mistake of publicly condemning those who stayed behind and almost accusing them of collaborating with the regime. Alas, this is precisely what divides like-minded people rather than helping them unite at this watershed moment. Such utterances prevent collective action. One of the most successful movements to date has been the Feminist Anti-War Resistance, with its well-developed network of branches and flexible structure. It is still not recognised as a full partner and participant in the opposition movement.

Another obstacle to building parallel democratic structures is the intergenerational differences in views between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ opposition at home and abroad, which prevents the continuation of a meaningful dialogue. In this context, it is important to understand that the new migrants are younger than the ‘old’ opposition which emigrated back in the early 2010s. The participants in the Free Russia Forum in Vilnius do not seem to fully represent the new generation of opposition, political migrants and activists.

Thus, the new wave of anti-war emigration has already led to the formation of new grassroots structures in post-Soviet states and some EU countries. Due to generational and value-based differences, these migrants are unlikely to become part of the Russian-speaking communities formed by migrants from earlier waves. Most recent migrants may also be wary of the ideas of politicians of an older generation in exile. This new wave of migrants are characterised by a comparable level of skill. Despite all the difficulties, new migrants have a greater capacity for collective action and cooperation.