Sources in the Russian government — quoted on March 4 by Meduza’s special correspondent, Andrey Pertsev — claimed that due to Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine, the government may suggest pushing back elections set for September 11. This would affect fourteen gubernatorial elections, six regional legislative elections, eleven elections to municipal councils, and elections to Moscow’s district councils.

Normally, apart from Moscow, none of the regions planning to hold elections in September would be considered tricky. For example, the ruling party’s popularity is particularly low in the Yaroslavl Region (United Russia’s official result in 2021 was 29.7 percent). But this is not a new phenomenon: United Russia has consistently had low support in this region for more than a decade, and the Kremlin learned to live with it. The ruling party had a comparably bad result in several of the remaining regions too — in Kirov, Tomsk, Novgorod, Sverdlovsk and the Republic of Mari El — but these have not led to a political earthquake, even as in Yaroslavl and in Mari El candidates from the Kremlin’s loyal opposition, supported by Smart Voting, won single-mandate districts in 2021. These regions are either too dependent on federal budgetary transfers to matter; or, the Kremlin has so far been able to find a combination of legal and political tools to manage them without massive popular support. In Moscow, online voting helped deprive opposition candidates from their victories, and created scant backlash.

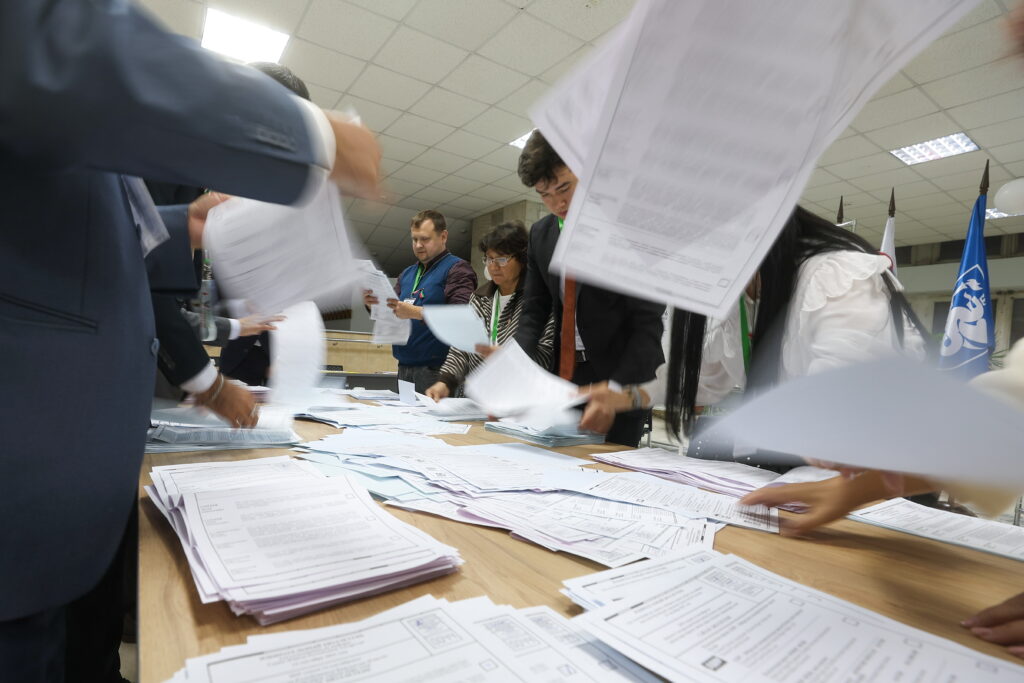

The government has a large toolbox to limit the chances and the impact of protest voting. The «municipal filter», which requires gubernatorial candidates to enlist the support of 5−10 percent of municipal deputies in their region, already significantly limits who can stand for office. The same goes for repressive legislation disqualifying «extremists». Control over regional electoral committees, exercised through regional legislatures dominated by United Russia, lets the authorities disqualify potentially popular candidates. Regional legislatures can tinker with electoral rules, which translate votes to seats, ensuring the dominance of the ruling party. Most have been reducing the weight of the proportional branch of their electoral system to the benefit of seats allocated in majoritarian districts since 2013 when a federal law loosened restrictions on proportionality. (Majoritarian districts benefit a weak ruling party as long as it faces a divided opposition). This year, up to half of regional capitals that face elections in September have planned to switch to a completely majoritarian system. Add to this the near-total elimination of independent media and a planned rollout of an opaque form of online voting, which in 2021 turned around opposition gains in Moscow. If things were still to go downhill for the Kremlin, the public administration reform adopted in December 2021 would allow the president to simply dismiss governors due to a «lack of trust» or put pressure on them in several other ways.

So if the Kremlin still contemplates scrapping these elections, this would suggest devastating expectations of the social and political state of the country in six months; a knee-jerk reaction to minimize potential risks and an admission of how support for the war is much thinner than officially claimed.

Too many variables

It is difficult to get a sense of how strong anti-war sentiments are. Surveys showing a strong pro-war majority, as Sam Greene of King’s College and Alexey Bessudnov of the University of Exeter pointed out, are of questionable value both because of their methodology and because people in repressed circumstances are likely to give an answer that they think will align with the majority opinion. Social media monitoring, which Mikhail Mishustin’s government ramped up as a source of input for the government’s Coordination Center, is of less use to find out about anti-war sentiments when people can face up to 15 years in prison for talking about the war in terms different from the government’s official account.

The authorities are trying to prevent the spread of news about the war by blocking independent media and even searching the phones of passers-by, but this will become more difficult as the war drags on. On March 9, just two days after Vladimir Putin himself said that conscripts would not be sent to fight in Ukraine, the Ministry of Defense had to admit that they were. The fact that some Telegram groups where local protest movements coordinated their actions now share information about the war and Russian casualties highlight the continued importance of these networks even as opposition personalities are jailed or exiled. Some regions, in which these protest networks are stronger, have seen local politicians or media publicly condemn the war.

It is also worth considering that while many Russian citizens may remain impervious to the war, believing it to be either a special operation or a defensive war, the society’s reaction to the ongoing economic collapse is difficult to predict. Protests in the past two weeks have focused on the war, but as trade disruptions, the collapse of the ruble, the Central Bank’s countermeasures and potentially sanctions on oil sales lead to problems in the real economy, we will see protests triggered by unpaid wages, mass layoffs, accelerating inflation, product shortages, and unbearable mortgage and consumer loan costs. These problems are not coming out of nowhere. Falling real incomes, inflation and growing indebtedness related to consumer lending are all problems that the government and the Central Bank have been trying to deal with over the past years, but have been unable to solve, because the political straitjacket in which they find themselves has allowed, at best, temporary solutions such as price controls or restrictions on loans, and not structural changes to how the economy is run (e.g. providing large-scale income support to citizens or improving the rule of law to stimulate private investment).

As sanctions hit the Russian economy, the government finds itself in a similar bind, but with much higher stakes. Several accounts have suggested over the past week that the government did not anticipate sanctions on this scale and did not prepare for it. The effects of overcompliance with sanctions — major energy, technology, aviation, financial and shipping companies leaving Russia — will be even harder to predict and hedge against. Certain industries, e.g. motor vehicle production, an important industry in pre-election Kaliningrad, can face mass layoffs or salary problems due to their dependence on imported parts, or the departure of foreign investors. This stands in sharp contrast with the image that Mishustin’s government has been trying to build over the past two years, namely that it may lack popular legitimacy, but through digitization and technocratic prowess, it is able to quickly address and mitigate problems on various levels. But the system was not created for solving problems on this scale, and it did not manage to penetrate the «deep state», either. In its present incarnation, the Coordination Center was little more than a scaled-up version of the «ruchnoe upravlenie» (manual control) previously exercised by the Presidential Administration and Putin.

Devolving problem-solving to regional governments will hardly eliminate these risks either. For one, it did not work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Governors may be the first to feel the heat when things go wrong (as some already do), but without vastly increased political and fiscal capacity they are unable to solve problems, especially considering the difficulty of poorer regions to retain or attract highly capable civil servants. The hollowing out of representative institutions and fiscal federalism over the past years has led to a situation where the president (and perhaps now the government) remains the only visible, tangible authority. Even as pandemic policies were nominally the responsibility of the regions, the Presidential Administration reportedly feared the effects of coercive policies such as compulsory vaccination or vaccine passports on Putin’s approval rating. Meaningful fiscal devolution, on the other hand, would undo two decades of fiscal centralization, at a time when the federal government’s system of distributing rents is already in disarray due to capital controls and the pressure on exporters to sell their hard currency in order to prop up the ruble. Orchestrating competitive-looking, but tightly controlled electoral campaigns in the regions when fiscal devolution means that there is actual money at stake would be extremely challenging.

The Kremlin may also feel elections are too risky to hold if there are questions about the loyalty of the administrative machinery that it relies on. If the Russian state loses the ability to ensure that public officials and personnel in state-owned companies are adequately paid, this could make driving up turnout or rigging elections problematic. As of yet, there is no indication that this is going to happen in six months’ time, however, given uncertainties about inflation and fiscal receipts as factories are forced to shut down or halt operations and sanctions may impact energy exports, the government could face difficult choices in the future. Another question is protest control. It is likely that even if there are severe disruptions in the functioning of the state, the government would prioritize paying security personnel. However, these forces may be overstretched if they need to exercise active crowd control at multiple locations — including in Belarus and in Ukraine — for a sustained period of time.. In the first eleven days of the war, more than 13,000 people were arrested across Russia at anti-war protests. Almost 80 percent of them were arrested in Moscow and in St. Petersburg, but arrests took place in more than 140 cities and towns. It is highly questionable whether the authorities can keep up this pace if the protests continue, but they may feel forced to do so, lest they are perceived to be lenient.

The flip side

There are thus good reasons why the Kremlin may want to forgo these votes. But cancelling them would, even in today’s Russia, be a radical step that comes with a range of risks.

Elections matter in autocracies too. For the authorities, they have a legitimizing function. This can happen in two ways. The results can showcase the strength of the ruling party or candidate vis-a-vias others — even if administrative tinkering and rigging result in overstating this strength — thereby nudging people to adapt their views to align with the majority’s. They can also showcase the authorities’ ability to engineer the results that they would like to see, even if it is far from their actual support, thereby demoralizing and demotivating the opposition. Since the government brought back direct gubernatorial elections in 2012, abolishing them again was never seriously discussed. Not even last year’s public administration reform, which significantly strengthened the political supremacy of the president and the federal government over governors suggested scrapping elections; perhaps to make governors personally invested in creating policies and structures that reliably bring ruling party votes.

But elections also matter to voters: even if they cannot result in a change in power, as long as they are nominally competitive, voters can use them to send messages to the authorities who will in most cases know the actual result. This happened in Russia in 2018 when a combination of an unpopular pension reform and local grievances led to four surprise upsets in gubernatorial elections; this is the effect that Alexey Navalny’s «Smart Voting» campaign tried to capture; and according to a Carnegie Moscow survey, even in 2021 Russians regarded elections as an important means of political signaling. Without elections, popular dissatisfaction in Moscow and in the regions would likely find another avenue.

Lastly, scrapping or postponing elections is always a radical move that signals serious problems. The authorities did not do it in 2021 even as Russia faced the deadliest months of the COVID-19 pandemic and there were serious questions about the viability of United Russia. In the present case, this decision may be taken as a sign that, contrary to the communication of the government, everything is not under control and Russia’s war on Ukraine is not a special military operation with a limited scope, even before the full extent of the economic fallout reaches voters. In a way, it would be a sign of weakness, an admission that the federal government’s control over public administration is loosening. Elites would almost certainly take notice — and so would, likely, citizens.