The 2016 Duma elections are long forgotten. The only fact that is remembered by a fairly significant share of Russian citizens is that those elections gave United Russia a constitutional majority, which the country’s authorities used to amend the Constitution. This is exactly why this fact is still remembered. In contrast, people have completely forgotten that the United Russia election list received just over a half of the votes in 2016 and performed only slightly better than in the 2011 elections, which were unsuccessful for the authorities. Meanwhile, the upcoming elections resemble the 2016 vote in many respects, with some differences, of course. Having analysed them, one can formulate some preliminary ideas about the election results that will be announced in September and, accordingly, about the structure of the supreme legislative body that will serve in the era of «zeroed-out» Vladimir Putin, possibly stretching over a dozen years.

Let us begin by looking at the similarities. The electoral system has not changed: it is still a mixed one, with a half of the Duma deputies being elected from party lists and the other half elected from single-member constituencies. The differences between the sets of parties admitted to run in the 2011 and 2016 elections were minimal. Over the past five years, the PARNAS party lost its electoral eligibility, the Patriots of Russia merged with Just Russia, whereas Civilian Power dropped out from the electoral arena. None of these parties received even 1% of the vote in 2011. New entrants include New People, Green Alternative and the Russian Party of Freedom and Justice. Seven parties are running again, having garnered between 0.22% and 2.27% of the vote in 2011. And, of course, the «Big Four» are still there: United Russia, Communist Party of the Russian Federation, Liberal Democratic Party of Russia and Just Russia (we will use the previous name since the new name seems too long). The total number of parties included in the ballot papers remained unchanged, i.e. 14.

Of course, this similarity is by no means accidental. The 2016 elections brought a result that the Russian authorities considered to be perfect, and for a good reason. Under these conditions, it would be foolish to make any changes. When it comes to the outcome of the elections based on party lists, the dispersion of votes among the eleven parties that did not exceed the five-percent threshold enabled United Russia to convert its rather modest result under the proportional component of the system from 54.2% to an impressive 62.2% of the vote. This in itself was close to the constitutional majority. However, United Russia achieved an overwhelming advantage thanks to single-member constituencies: having won in 90.2% of them, United Russia elevated its majority to 76.2% of the vote.

In the course of five years, the public support for United Russia has dropped considerably. We will not go into speculation as to whether this has been due to the erosion of Crimean euphoria, a sharp decline in the living standard or some other factors. There is no need to assess the adequacy of Russian opinion polls: they may well be capturing the actual trends. In August 2016, the Public Opinion Foundation (FOM), fully loyal to the authorities, established that 45% of those surveyed intended to vote for United Russia. In August 2021, the respective share was 30%. It should be remembered that these data originated from a provider associated with the authorities. To some extent, they reflect the estimates made by United Russia’s strategists and the presidential administration. Quite obviously, they have no reason to be particularly optimistic. If the elections were held under a purely proportional system, United Russia would have little chance of gaining not only a constitutional majority, but even a simple majority of the vote.

Let me reiterate that the figures from Russian opinion polls are problematic, to put it mildly, but, much like the Russian authorities, I am not inclined to view them as plucked out of thin air. Nor do I share the view that the «actual» support for United Russia among the citizens is declining towards zero. In relative terms, United Russia seems to remain the largest player in terms of potential electoral support among parties allowed to run in Russian elections and to campaign on terms and conditions defined by the authorities. It is quite likely that if the group of admitted parties included the opposition, not controlled by the authorities, and if the opposition were allowed to conduct a meaningful and active campaign, with criticism towards the authorities, the superiority of United Russia would go up in smoke. However, the Russian elections take place in an authoritarian rather than a democratic political context. As long as this context persists, United Russia will always get a considerable share of votes from people who genuinely support it.

This support comes from a variety of sources. Quite significant groups of the population (such as security and law enforcement agencies, bureaucrats, officials in state-owned companies, to name just a few) are quite capable of seeing a connection between their own interests and the existing regime. They know that a change of the regime would significantly undermine their personal situation. And an even greater number of people, I believe, consider their current situation satisfactory and are afraid of losing it, as the risks associated with adapting to new conditions are seen as high. Unfortunately, the experience of painful changes of the early 1990s makes people inclined to hold on to such beliefs. The propaganda in the publicly accessible media may be significantly exaggerated, but it is nevertheless a real factor. However, I think that the propaganda does not as much build support for the regime as it allows its supporters to rationalise and explain their support in socially acceptable ways. One way or another, the support for United Russia is real. However, it has fallen considerably since 2016, and the «party of power» is not likely to get more than 30% of sincerely cast votes.

Quite clearly, people vote for United Russia not only because they genuinely want to, but also as a result of coercion, or more or less direct vote-buying practices. It is difficult to estimate the scale of such voting, but the coercion and bribery mechanisms have been constantly improved. Thus, one can be fairly confident to assume that the declining numbers of voters who sincerely support United Russia will be mitigated by these mechanisms to some extent. Also, direct falsifications will play a role.

Moreover, United Russia is unlikely to replicate its 2016 result from the party-list vote. Given that its performance was quite modest even back then, the «party of power» has no other way to win a significant majority in the Duma but to hold a victory in most single-member constituencies. Indeed, even simple arithmetic suggests that if United Russia is victorious in more than 90% of the constituencies, as it was in 2016, it would capture the much wanted two-thirds of the seats even with 40% of the vote under the proportional system.

Of course, one might assume that since the overall support for United Russia is declining, this will also affect the results in single-member constituencies. However, this thinking fails to take into account the special mechanics inherent in electoral systems based on relative majority. One does not need to enjoy the support of whole lot of voters to win a constituency. It is enough to outperform all the other candidates, and, assuming a significant dispersion of votes among the candidates, this is quite achievable not only with 30%, but even with 20% of the vote. Meanwhile, the number of candidates in single-member constituencies is considerable. This is primarily due to the fact that each party running under the proportional system is trying to nominate its own candidates. Small parties hope that this will raise their visibility and bring extra votes to the party list, even if their candidates have absolutely zero chances of winning. In fact, this is the main benefit that the authorities derive from small parties participating in the elections.

Thus, the combination of a rather modest result under the proportional system and success in the vast majority of constituencies allows United Russia to hope for a very significant majority in the Duma, perhaps even the constitutional one. Can opposition-minded voters counteract such an outcome? Yes, they can. First of all, they can do so if dispersion of votes in constituencies can be prevented, which can be achieved by voting for candidates outside the «party of power» who have the best chance of winning over United Russia candidates. This is the aim of the strategy known as «smart voting.»

This strategy, proposed by Alexei Navalny and his supporters, assumes that opposition-minded voters will use recommendations developed through the analysis of data from constituencies, available electronically upon request. Let me emphasise that while such recommendations may bring significant benefits, many voters can conduct their own analysis of the situation in a constituency, and come to quite plausible conclusions as to which candidate poses the greatest threat to the respective United Russia candidate. Essentially, this strategy is based not on the method, but on the goal, i.e. to reduce United Russia’s representation in the Duma.

In most cases, the potentially strong opponents of United Russia in constituencies are communists, and sometimes the nominees of the Liberal Democratic Party or Just Russia. This means that this strategy is definitely not suitable for voters who believe that there is no difference between United Russia and these three parties. Without going into a detailed criticism of this approach when applied to Russia, let me point out that it is inconsistent with the conclusions made in the literature about the comparative dynamics of democratisation processes. A decreased representation of the dominant party will not only be a symbolic defeat, since it undermines the authorities’ claim that they reflect the will of the vast majority of citizens, but, more importantly, it will create possibilities of greater autonomy for other parties represented in the parliament. However, such an opportunity may remain unused even if it does arise. However, international practice of democratisation processes shows that the relative autonomy of loyal opposition can make a significant contribution to the process and shift the direction of change whenever such change is triggered by some serious political stimuli.

Quite understandably, any hopes to weaken United Russia’s position will be dispersed if opposition-minded voters simply decide not to go to the polls. The Russian party system has been deliberately designed by the authorities to push the opponents of the regime into absenteeism. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation and the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia are niche choices: the former is ideologically profiled in a way that is unacceptable to most voters while the latter relies for support solely on the highly problematic figure of its leader. The electoral appeal of Just Russia is even more questionable. On the one hand, small parties are controlled by the authorities but, on the other, they enjoy such a low awareness that they cannot expect to go beyond the 5% threshold. Yabloko’s claims to be the main democratic party are not groundless. However, as attested to by public opinion polls and numerous results of actual voting, these claims do not seem convincing to a significant proportion of opposition-minded voters.

If opposition-minded citizens accept the imposed rules of the game and fail to show up at the polls, only a few nominees from the communists, liberal democrats and Just Russia will make it to the Duma alongside United Russia, spring-boarded there by their very few sincere supporters. The extended representation of these parties has long been ensured largely by voters who do not genuinely support them but who vote for them simply because those parties seem, for lack of better options, a plausible alternative to the incumbent authorities. This is why United Russia’s dominance in the Duma would remain unchallenged if masses of opposition voters stay at home on election day.

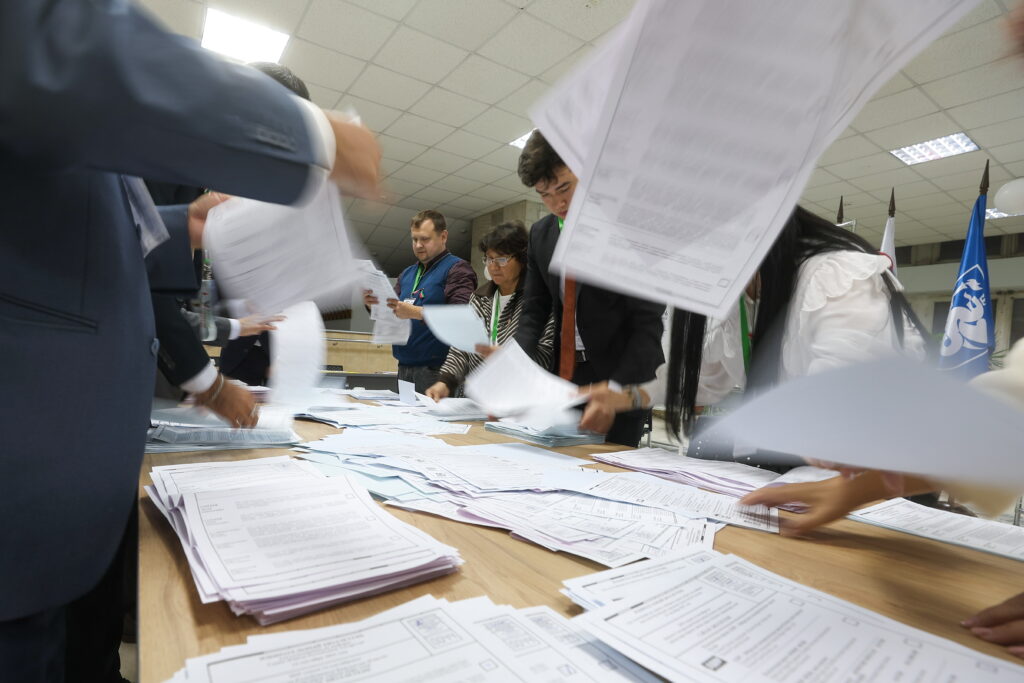

If this is the case, the authorities would not even have to resort to falsification. If almost all people at the polls cast their vote for United Russia, there would be no need to engage in fraud. And that, clearly, would be entirely in line with the regime’s preferences. Having learnt their lesson from the 2011 Duma campaign, not to mention the recent events in Belarus, the authorities know how dangerous it would be to attempt direct and massive voting fraud. Of course, if opposition-minded citizens do show up at the polling stations, fraud would be inevitable. Russia’s elections, with their total lack of effective monitoring and three days of voting, provide fertile ground for such practices. However, the authorities would then have to count with the related risks. Moreover, one should bear in mind that while election results get almost completely falsified in some regions, the possibilities of electoral fraud are not so high in other regions, particularly in some of those with large conurbations.

To sum up, we can say that United Russia stands a good chance of winning a huge majority of seats in the new Duma. However, this outcome is not a foregone conclusion. Opposition-minded voters can indeed influence the structure of the Duma by: 1) going to the polls, 2) voting for the strongest opponents of United Russia in their respective constituencies, and 3) trying, as far as possible, to avoid dispersion of party-list votes by choosing those who have a chance of exceeding the 5% threshold. Whether this opportunity will be seized remains an open question.