The past few months were a downward trend for the Russian economy. The Ministry of Economic Development had to revise its forecasts downward. Real incomes in the first half of the year were falling significantly faster than the last year; many July indicators hint at a coming recession. The only positive factor is persistently high oil prices. Even the trade spat between Washington and Beijing and the ongoing slowdown in the Chinese economy cannot drive them steadily below $60/barrel. Yet the approaching global crisis is being talked about more and more; its onset would bring down commodity prices. Thus, Russian officials start to comment on the possible impact of falling oil prices on the Russian economy.

A classic example of an optimistic position on this subject? A recent interview with the head of the Ministry of Economic Development, Maxim Oreshkin. He stated here, if you omit the details, that Russia is ready to survive an oil price drop to $40/barrel. At the same time, he claimed, Russia “will not experience serious pressure on the domestic economy and financial market”. Partly, there are grounds for this: all budget revenues this year exceeding an oil price threshold of $41.5/barrel went to the National Wealth Fund(NWF). The budget itself is drawn with a record surplus; 2.75 trillion rubles in the past year and 1.56 trillion in the first half of this year. The volume of the NWF by the end of the year will reach approximately 10 trillion rubles. The question will arise about the directions of its investment. Finally, the Kremlin has the instrument of devaluation always at its disposal, which without serious adverse effects will increase the ruble income of the budget even in the case of a 15-20% reduction in oil prices.

However, the situation is more problematic than it might seem for two reasons.

On one hand, the dominant assessment of “oil revenues” is not that credible. Since 2006, the Ministry of Finance has been calculating the volume of “oil and gas revenues” of the budget, which only once exceeded 50%. As per official figures, in 2018 the figure was 46.3%; in the first half of 2019 – 41, 7%. However, independent studies show how this amount does not include many taxes, duties and excise taxes. These are often paid by oil and gas companies except for mineral extraction tax, export duties and the recently introduced tax on added income from hydrocarbon production. Unaccounted income over the past year alone exceeded 1.5 trillion rubles – so if oil prices begin to dive, tax revenues from oil companies will decline; thus, the current budget (even assuming that all export earnings above the “cut-off price” will continue to flock to the NWF) will go into deficit and the budget rule will have to be reviewed. This problem is rarely raised today. The government does not want to pay too much attention to it. But it must be borne in mind that lowering prices for raw materials will have more serious consequences for the Russian economy. Even if it happens as if in a vacuum – i.e. without provoking other consequences and without being associated with attendant circumstances.

On the other hand, a drop in prices must be in a broader context of causes and effects.

Today in Russia state officials and the expert community prefer to say that price reductions can begin from further overproduction of oil and gas in the United States. Or as a result of a change in the joint position of OPEC+ countries. However, even a reduction in US imports does not prevent other oil producers from finding a way to the market. Besides, the effect of the shale revolution in the gas sector is rather small. So consider if in the mid-2020s the world will experience a shale revolution – both because of the adoption of new American production methods by other countries, and because of the “transition of quantity into quality” in the field of renewable energy sources. Nothing like that will happen in 2020-2021 on a scale that could drop oil prices by a third or even more. A decrease to $50/barrel is likely, but anything more significant is unlikely. The Russian economy is capable of withstanding such a test – at least for several years.

A drop of prices of up to $40/barrel and lower, though, as the minister speaks of in the interview, is possible only in the context of the global crisis. It will be fraught with several important consequences for Russia.

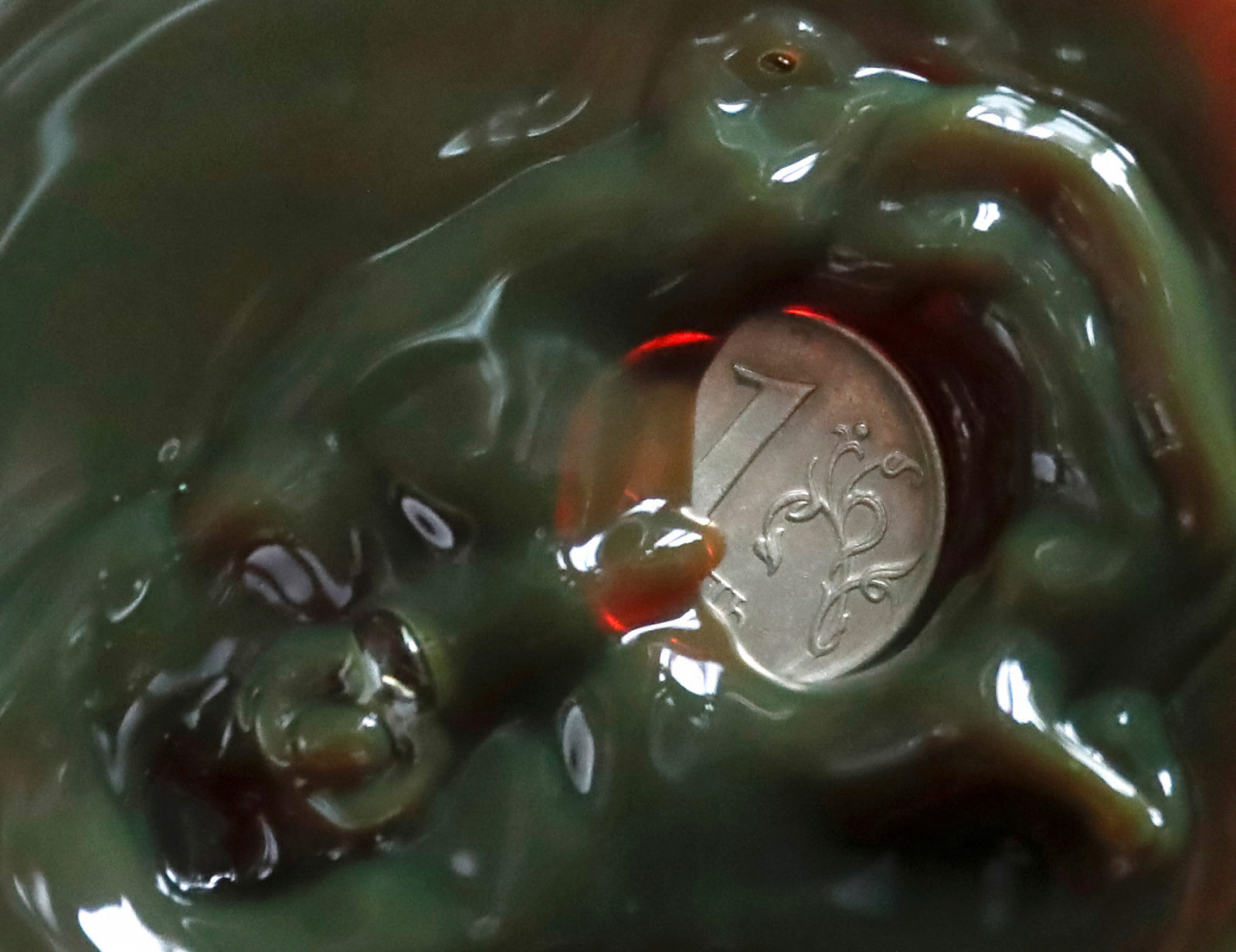

First, the foreign exchange market players associate the ruble exchange rate with oil prices. This linear relationship has its limits. Lowering oil prices to $50/barrel will easily lead to a rate of 70 rubles/dollar. But if they rush to $40/barrel, the Russian currency may not be able to keep up to 80 rubles/dollar. The floating rate system assumes the absence of intervention – as we have seen it at the beginning of 2016– when then oil prices of $29-30/barrel corresponded to a rate of 83.6 rubles/dollar. Under the new conditions, the situation is likely to be more dramatic. In the event of a global crisis, the dollar will grow against all currencies due to investors withdrawing from risky assets. This was not observed in 2014-2015, as it happens. And thus, a price of $40/barrel may mean a ratio closer to 85-90 rubles per dollar.

Second, the volatility of the foreign exchange market and doubts about the stability of the budget filled with petrodollars will cause a serious outflow of investments from the ruble loan market. Today, according to the Central Bank, foreign investors control 30% of the bonds on the Federal Loan Obligations market with a nominal value of 2.6 trillion rubles. Such a process will cause a rapid increase in the cost of loans in Russian currency; the Central Bank would likely carry out several increases of the interest rate. This is now the main tool to maintain the exchange rate. All this in a few months will destroy conditions for cheap lending to enterprises and citizens; it will freeze the mortgage market, the population’s purchases of real estate and durable goods will decrease. In turn, that will slow down economic growth by 1-1.5% of GDP if the rate rises by 4-5% per annum. Recall in 2014 how he Central Bank at a meeting of the Board of Directors on December 16 raised the interest rate from 10.5 to 17.0% per annum.

Thirdly, both a decrease in foreign currency inflows into the country and a drop in the ruble exchange rate will create conditions for a sharp reduction in both state and private investment. Last year’s state investment of 16.98% of GDP may fall to 14-14.5%, which looks disastrous even against the backdrop of the most developed countries.

Most likely, even in conditions of oppressed demand, inflation will speed up to 10-11% per annum, which will become the basis for banks to maintain high interest rates on loans. A fall in investment will result in cost optimization, the departure of many companies “to the shadows” and a reduction in revenues to extrabudgetary funds. And I’m not even mentioning that the deterioration of the financial situation of the oil and gas sector will inflict a severe blow to related sectors of the economy.

Fourth, the return of instability in the financial markets will no longer cause, as in 2014, the rush demand. A decrease in the available funds of the population will see to that, and will only lead to its further impoverishment. In Russia, “goods for the poor” are traditionally the fastest growing in price; monopolies will not fail to take advantage of the situation to raise tariffs. In addition, one should not discount that in the event of such a sharp change in economic conditions, large oil companies (especially Rosneft and Gazprom) will likely need more tax benefits or will try (as they already did, although without much success) to get some funds from the NWF; both will reduce the possibility of financing “social” budget items and reduce the size of the “safety net”.

In other words, the fall in oil prices against the backdrop of a serious global crisis will hit Russia in two ways. It will change expectations of business entities, raising credit rates and launching the withdrawal of investments. It will reduce investment and a spark a general economic downturn; real incomes of the population will also come down; the possibilities of domestic entrepreneurs for marketing their goods and services will be hit. At the same time, it may well be that, in purely financial terms the budget will not be in a critical condition: the NWF funds are allocated in foreign currency assets, thus ruble devaluation will only boost those funds. But the state will be careful about spending reserves. Still, a drop in prices well below $50/barrel will likely trigger a recession of 2–2.5% of GDP over a 2–4 year horizon; attempts to get out of it through pumping up state investments cannot be expected. The authorities understand that in such a situation the allocated money will be stolen and withdrawn from the country. No matter how complicated the situation, there will always be a fear that it will soon become even more difficult, and it is not worth spending reserves now. Thus, in the event of a fall in prices to the levels indicated by Maxim Oreshkin, Russia will face a full-fledged recession instead of continuing the current stagnation.

Such a development of events is dangerous due to the political situation. The status quo is characterized by growing doubts about the ability of the authorities to preserve the economic achievements of the early Putin era. Considering real incomes have fallen by 10-12% over six past years, adding another 5-7% drop in one year may turn those doubts into mass discontent. There is no way that business today will be able to keep the prices at the same levels as it tried to do until the last in 2014-2015.

Although I am skeptical about the ability of the Russian population to organize mass disobedience in a way which would force the Kremlin to change its course (I’m not even talking about regime change), it seems to me that a powerful fueling of the budget with oil revenues is the main reason for the stability of the existing regime in the country today.