Russia’s policy in the Middle East has a certain peculiar characteristic, eagerly emphasised by pro-government experts: Moscow can simultaneously conduct official dialogue with warring parties. Today with Israel and Iran; tomorrow with the USA and Hezbollah; then, Turkey and the Kurdish Democratic Union Party. The role of a non-aligned state pushing multilateralism as a fairer form of relations seems to have helped Russia to ‘return’ to big politics, as remarked by Putin back in 2003. However, Russian foreign policy has been excessively intrusive in recent years. Moscow has been courting everyone to impose a ‘dialogue of equals’ on Washington, its main opponent.

This has been particularly evident in the Middle East. To reinforce its position in the region, the Kremlin is trying to play on the contradictions between traditional allies (e.g. the USA and Saudi Arabia) and take a more sustainable position in countries where the crisis has reached its peak. Sometimes Moscow is trying to be instrumental in implementing a policy of diversification of political ties, doing it quickly and loudly. Such tactics are typically used mostly by non-state actors, who do not have the means to engage in permanent combat according to the prevailing rules. While the Kremlin has sufficient military resources, its modest economic means prevent it from gaining sustained loyalty even from seemingly organic allies, let alone tactical ones.

The year 2020 highlighted all existing flaws in the relations between the Kremlin and its Middle East partners. It forced the Russian leaders not only to criticise and blame, but also to propose urgent anti-crisis solutions and sometimes even to retain neutrality.

In December 2019, Moscow, Beijing and Tehran held the first joint naval exercises in the Indian Ocean. These had obvious political undertones. For Russia, participation in such manoeuvres demonstrates a harmony with Iran, a country which is also allegedly unfairly suffering from sanctions. It also highlights Russia’s importance to the USA, which has fallen into disagreement with its allies in Europe on Iran policy and the nuclear deal. Two events this year sobered Moscow. One, the U.S. operation conducted on 3 January 2020 to kill Qassem Suleimani, commander of the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Then came the later destruction of the Ukraine International Airlines Boeing 737 by Iranian air defence. By inertia, Moscow seems to have previously entrusted itself to Iranian propaganda. However, the Iranian leaders had the guts to admit that its air defence had mistakenly hit the plane.

The condition of Iran’s overall stress response system (after all, the plane was shot down near Teheran, far from the potentially dangerous areas that the USA could hypothetically strike from) ultimately marginalised the issue of Russian arms and military equipment supplies to Teheran, although the arms embargo expired on 18 October 2020. The pandemic did not prevent Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif from becoming a frequent visitor to the Russian capital or the Iranian Defence Minister Amir Khatami from coming to the ‘Army 2020′ military forum. However, the presence of the Iranian delegation at the forum did not attract much attention from the media, previously rather optimistic about the sale/purchase of military equipment samples.

Likewise, this year has not been easy with Iran’s regional antagonists: Saudi Arabia and Israel.

The oil market crisis provoked by Moscow during the pandemic should dispel the myth that Russian actions in foreign policy and economy are calculated several steps ahead and united by a common idea: to show Putin’s Russia as a balanced, consistent and reliable player who can be a partner in negotiations. After the OPEC+ deal to cut oil output at the end of 2016, which stabilised prices, it became clear that disagreements were resolved only temporarily. In fact, the most acceptable way out of this situation was an agreement on a controlled increase in output. Based on the opinion of the government-controlled oil companies, the Kremlin refused to extend the agreement in the face of falling demand, provoking Saudi Arabia to resist. Although the players then managed to reduce the emotionally charged atmosphere, the ‘price war’ during the pandemic accelerated the fall in oil prices and led to costs for the Russian economy. In December 2020, the OPEC+ countries laboriously agreed to increase oil output by 500,000 barrels per day from January 2021 onwards (four times less than planned). At the same time there could be further problems at the end of the first quarter.

After the warm reception of the Russian delegation at the opening ceremony of the ‘Candle of Memory’ event in Jerusalem, which was the first occasion for the Russian president to speak freely and emotionally abroad about his concerns about attempts to revise the outcome of World War II, it seemed Russia and Israel had overcome all differences. In December, however, the Russian Ambassador to Israel, Anatoly Viktorov, unexpectedly told The Jerusalem Post in an interview that the Jewish state is more destabilising to the Middle East than its rival Iran. Moreover, the diplomat made an attempt to defend Tehran-loyal Shiite military and political organisations, some of which had previously murdered and kidnapped Soviet diplomats, but now allegedly act as allies of the Kremlin in the fight against terrorism. Moscow tried to smooth things over, but the diplomat’s remarks are not the first ones of this kind. They can be attributed to Russia’s presence in Lebanon and Beirut’s place in the scheme to circumvent international sanctions against Damascus.

Troubles with Turkey

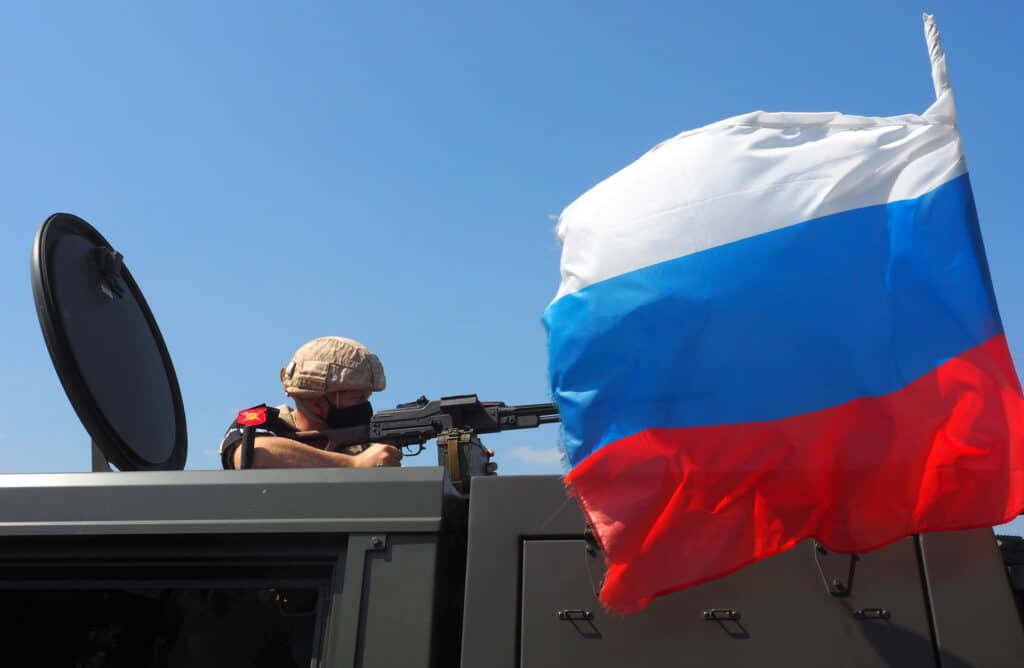

The year 2020 has also shaken off illusions in Russian-Turkish relations. The escalation in Syria’s Idlib in February, which ended with heavy losses among Bashar al-Assad’s forces and resources as a result of Ankara’s strikes and a new deal between Putin and Erdogan, was replaced with competition in Libya. Tripoli-loyal forces, backed by the Syrian opposition and Turkish combat drones, began to press Haftar’s forces on all fronts and deprive him of the support of some tribal leaders. After the forced withdrawal of Russian forces in the Tarhun area, Haftar’s defences crumbled there too. As a result, Moscow had to redeploy its PMC groups and shore up the remaining Panzir-S1 SAM system based on KAMAZ-6560 (such serious air defence systems could have been supplied to PMC ‘archaeologists’ either from the Russian Armed Forces reserves or upon a special order, or leased from the Syrian armed forces). Then, to strengthen its arguments, Russia carried out a clever act with the redeployment of aircraft via Syria to Libya. By September, Russian-Turkish relations were put to the Karabakh test. Moscow and Ankara seemingly managed to overcome their differences by agreeing to establish a coordination centre in Aghdam, but not for long.

Elsewhere, what became the litmus test for Russia’s effectiveness is the petrol and food crisis in Assad-controlled territory in Syria. This area had marked the beginning of Russia’s ‘return’ to the Middle East. Even now, there is no talk of a political settlement. Even the ‘decorative’ Constitutional Committee, which has met four times since October 2019, has not arrived at any real decisions outside the protocol. In the seemingly post-conflict period, making a choice between the former approach of simulating stability in the country and the decorative reform proposed by Moscow, combined with reconciliation with the puppet opposition, Damascus is taking the third route: it is simulating ‘democratic’ elections without undertaking any political reforms. Apparently, the Kremlin agrees with it. During his September visit to Damascus, the head of Russian diplomacy Sergey Lavrov said that the Syrian presidential election did not depend on the work of the Constitutional Committee. This statement was sensational. Russian diplomats reluctantly admitted over the years that the 2021 elections would be an exam. If passed, these would determine the success of the stage set by Moscow on Syria.

Quite predictably, the conference on refugees held in Damascus on 11−12 November failed to produce any of the results that Assad’s allies are still hoping to see while they unsuccessfully try to ‘sell’ his relegitimisation to the international community. As before, the repatriates are in no hurry to return to their homeland. There, they can expect filtration camps; interrogations by the security services; ruined housing (the removal of debris must be paid for, which is not cheap by Syrian standards) and service in an army that has been fighting not only against radicals but also against its own population for all these years.

Because of the sanctions against Syria, all operations by interested Russian companies (Moscow keeps their names secret to circumvent the sanctions) are going through a chain of intermediaries. Those companies and players who publicly venture to rebuild the territory controlled by Assad have nothing to lose. On 30 November, the Syrian Ministry of Economy issued registration certificates for the branches of two companies linked to Yevgeny Prigozhin: Velada (block No. 23) and Mercury (No. 7 and 19) with capital of USD 7.3 million and 7.35 million respectively. The offices of these branches are located in the Sha’alan neighbourhood of Damascus, next to the branch of Gennady Timchenko’s Russian company, which opened slightly earlier but had long been active in Syria in port management in Latakia and phosphate mining in Homs. These are the ‘drivers’ of the Russian-style reconstruction of Syria. That is, if we neglect single-point essential projects such as the restoration of the Tishrin Dam (Aleppo) and Baath Dam (Raqqa), which were built by Soviet specialists.

A compromise with the Gulf countries that the Kremlin has been actively interacting with during all these years could be a way out. However, the Sunni monarchies, which have restored formal or informal relations with Damascus, are pursuing their own goal: they promise investments in exchange for containing their regional opponents, Iran and Turkey. But they are in no hurry to make serious investments (also because of the American ‘Syria Caesar Act’). The position taken by Washington and EU countries, meanwhile, is quite clear: participation in the reconstruction of Syria is not possible without implementing UN resolution No. 2254 or formalising a transitional Syrian government to reform the Syrian statehood. Neither Damascus nor Russia can agree to that. So, they are trying to simulate a compromise by substituting this government for a stillborn Constitutional Committee, which has never really started its work and is unlikely to be able to do so in 2021. In other words, Moscow, which has insistently demanded ‘a dialogue of equals’ with the West, can hardly offer anything constructive in this dialogue. It only promotes the idea that Assad must be accepted because «there is no alternative to him.»

Without fears of their own democratic replacement, the Russian authorities can afford to delegate the power to fight abroad to mercenary structures and the power to do business with economic companies with non-transparent profit-earning schemes and, consequently, a ‘grey’ scheme with no taxes paid. This is exactly the formula for Russia’s notoriously ‘consistent’ official policy in the region: reactive decisions are cemented by other reactive decisions, creating an appearance of a strategy.