The sanctions imposed on Russia after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine thrust the Russian car industry into crisis. It manifested itself most visibly in the largest collapse in car production in post-Soviet history and a massive market takeover by Chinese brands. However, the industry has shown signs of recovery in recent months: between January and September 2024, passenger car production increased by 39% (to 508,000 vehicles), sales leapt by 61% to 1.15 million cars, and the weighted average price of a new car stabilised at RUB 3 million. At first glance, these data suggest that the car industry will soon return to its pre-war performance. However, if we look at the situation from a different angle, through the prism of the supply of car components and spare parts, the industry’s prospects seem far less optimistic.

The auto components industry before the war

The industry has traditionally been oriented towards large car manufacturers. In 2005, Russia introduced the ‘industrial assembly’ regime. Following many global car companies that built their plants in Russia, manufacturers of the world’s leading brands of automotive components also rushed into the country, among them Magna, Faurecia, Asahi Glass, Delphi Automotive, BASF, Johnson Controls, Bosal and others. Taking advantage of the right to duty-free import of almost all parts and raw materials, those companies located production facilities in various regions, providing car plants with components and helping them to increase the degree of localisation. As a result, Russia saw the arrival of full-fledged factories operated by subsidiaries of foreign brands, producing plastic parts for car bodies and interiors, auto glass, headlights, suspensions, exhaust systems, electronic engine control systems, window lifters, air-con systems, fuel tanks, cylinder heads for engines and other crucial automotive components. A well-developed component base emerged, alongside the formation of large automotive clusters combining car and component manufacturers, thus improving product quality and developing the relevant human resources. The Russian automotive industry gradually became internationalised, blending into the global supply chains and developing exports, and the capacity of the secondary market for automotive components reached over USD 27 billion by 2022.

However, not everyone perceived these trends positively. Many domestic auto component manufacturers were losing their market, falling behind localised foreign competitors both in terms of price and product quality. The domestic automotive component industry felt that Russian car manufacturers were unjustifiably favouring foreign components, and the government’s industrial policy seemed ‘toothless’ in this regard. Criticism was also voiced by ‘patriotically-minded’ experts, who feared that integration into global production chains would deprive the country of its industrial sovereignty while the Russian cars traditionally produced in the country would lose their authenticity and uniqueness.

Nevertheless, the automotive industry was expanding: by 2022, the average degree of localisation had reached 50−55%, and the government was allocating significant funds for import substitution projects for automotive components, setting ambitious goals to push the localisation of production further.

The post-war realities of car manufacturing

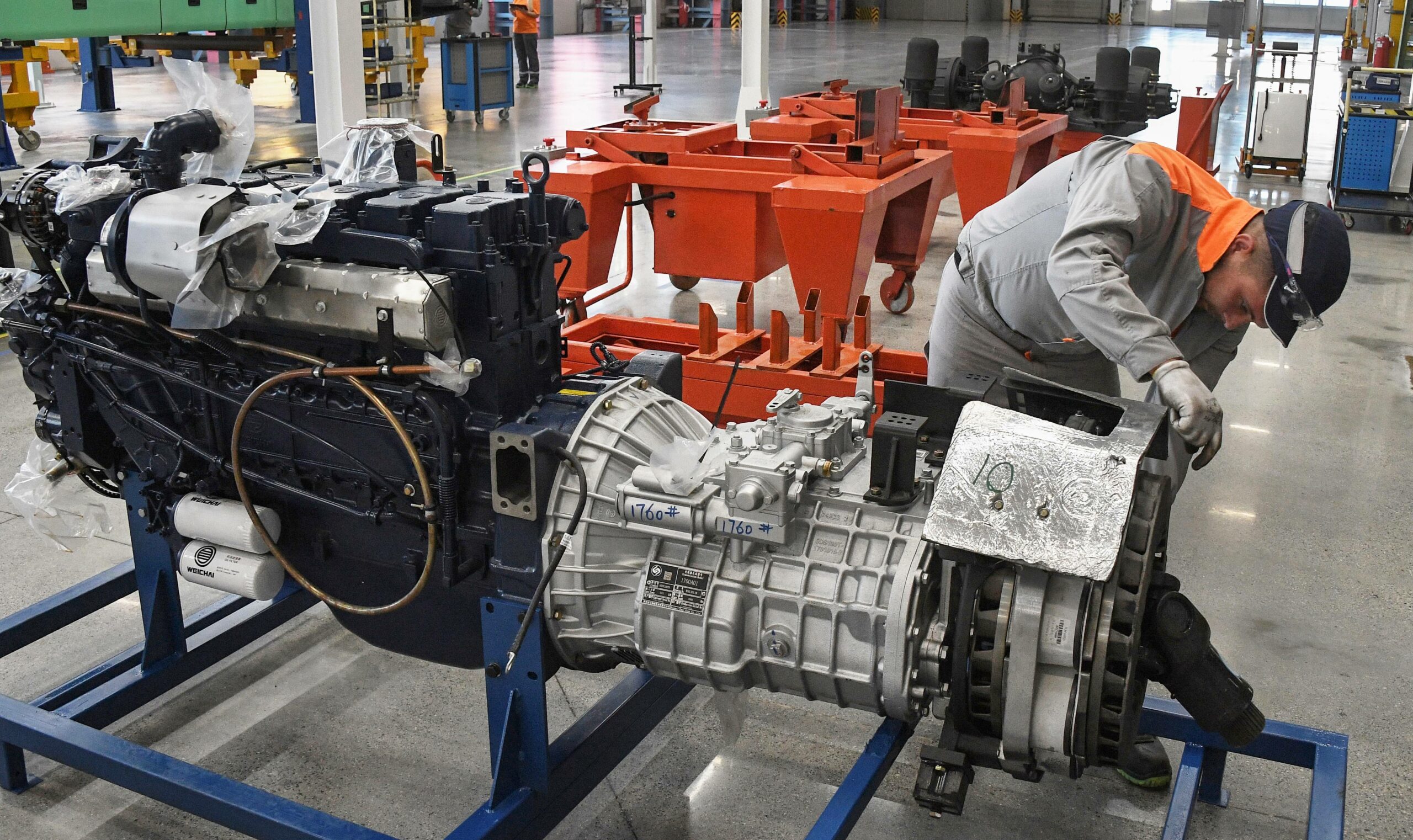

After the outbreak of a full-scale war, car plants in Russia faced an acute shortage of components, their supply being banned or restricted due to sanctions. Moreover, many international manufacturers of automotive components suspended operations in Russia, which resulted in shortages of critical components and spare parts. This forced Russian manufacturers to carry out a large-scale reconfiguration of their supply chains, engaging in an active search for local manufacturers and suppliers from China. However, this task has remained difficult until today. For example, disruptions in the supply of key components forced AvtoVAZ to permanently stop the production of the Lada X-Ray model, while KAMAZ had to suspend production of trucks with Mercedes-Benz cabins and return to obsolete models.

This reconfiguration is vital for all Russian automakers (AvtoVAZ, GAZ Group, KamAZ, Moskvich, Sollers and others), many of which are under strict U.S. sanctions. This effort is extremely labour-intensive and calls for significant material, financial and human resources, as well as time to develop, test, trial and certify new components. In essence, resources are spent on ‘reinventing the wheel’, since the missing components were easily procured on the world market before the war, meeting high quality standards. The industry would resort to import substitution only when it was expedient and economically justified. Today, however, in order to ensure that assembly lines operate without interruption and production plans are fulfilled, carmakers are forced to substitute a significant proportion of critical components in a rushed manner or look for suppliers who would be willing to accept the risks of secondary sanctions and payment problems. As a result, the cars produced by Russian plants are often of low quality, prone to defects and frequent breakdowns.

The situation is additionally complicated by the serious shortage of original spare parts. The market has seen the arrival of multiple manufacturers of counterfeit and duplicate parts: according to some estimates, they account for up to 30% of the market, and one in four car mechanics reports having had to repair cars following a failure of counterfeit parts.

Post-war realities of automotive component production

Supply chain disruptions have also affected Russian manufacturers of automotive components since the production of items such as fuel tanks or thermoplastic products that had been established in Russia calls for the supply of subcomponents, many of which are still imported. The situation is similar with internal combustion engines and electronic control units: their local production remains dependent on imports of electronic components and semiconductor sensors. Even basic non-electronic elements, such as valves, injectors, ignition coils, brake and fuel systems, and many other second- and third-tier subcomponents often have to be imported since they are not produced locally.

Difficulties with the supply of subcomponents have also affected those automotive component manufacturers whose plants have been transferred from foreign to Russian owners. For example, the plant of the French company A. Raymond Group in the Nizhny Novgorod region, which was bought out by the recently sanctioned Cordiant holding, depends on imports of subcomponents. Additionally, the European-made technological equipment used at this plant requires regular maintenance and renewal, which becomes problematic and expensive under the sanctions. It is almost impossible to find similar equipment in ‘friendly’ countries.

Many auto component manufacturers localised in Russia were hoping for the growth of car production and stable demand from foreign car manufacturers opening their plants in the country, and were confident that localisation projects would bring return on investment. However, the actual three-fold reduction in car production and the transition of most Russian plants to large-scale assembly platforms for Chinese cars mean that the demand for the products offered by Russian subsidiaries of foreign brands has disappeared. Certain automotive component manufacturers also exported some of their products to foreign markets — for example, Bosch Russia did so with spark plugs. After the sanctions were imposed, they faced a blockage of export supplies, which aggravated the economic difficulties at those enterprises and actually locked them within the domestic market.

Bleak outlook

Despite visible signs of recovery in the Russian automotive industry, structural problems resulting from sanctions pertain, indicating serious challenges for the industry. With international suppliers going out of business, dependence on foreign subcomponents and shortage of original spare parts reveal the vulnerabilities of the automotive component base.

Today, virtually all production of automotive components in Russia relies on domestic and Chinese suppliers of subcomponents and technological equipment. At the same time, Russian component manufacturers are forced to focus mainly on the domestic market, as their products are in demand only among domestic car plants. Given the shrinking market, sanctions-related risks, logistical constraints and other restrictions, those players are forced to raise prices (a phenomenon which is also observed among their Chinese competitors) and jump on the bandwagon of the widespread component price rises in the country.

On the one hand, this may lead to the effect that has been long awaited by the Russian authorities, namely a high degree of localisation for cars produced in Russia (at least 80%). However, the benefit of achieving such a goal is doubtful, even for AvtoVAZ management. On the other hand, there is a significant risk of negative consequences: low quality of cars, safety problems and continued price growth, all of which may finally undermine the sustainability and competitiveness of the Russian car industry in the long run.