The Russian government presented its draft budget for the next three years at the end of September (you can find a full set of documents here). On October 23, the bill had its first reading in the State Duma.

Following years of consolidation, the new budget is described by the Russian Ministry of Finance as one of economic stimulus. Is this an apt description?

Strong budget and weak economy

The Russian authorities have made impressive adjustments to the federal budget since 2014, when oil prices plummeted and Western sanctions against Moscow first hit. Reacting to this double shock, Russia cut its budget. After depleting its Reserve Fund by 2017, the country started to accumulate sovereign reserves.

The indicator of the budget’s dependence on oil and gas production and exports, the non-oil and gas deficit (the difference between non-oil and gas revenues and total expenditure) decreased from 10% of GDP in 2009-2016 to 5.8-5.9% of GDP in the 2020-2022 draft budget.

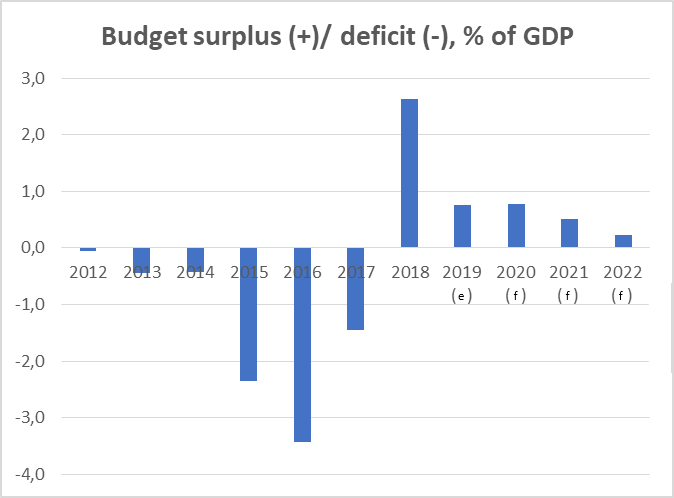

Budget consolidation, i.e. cutting spending in real terms, continued from 2015 to 2018. In the meantime, the budget deficit of 3.4% of GDP (2016) transformed into a budget surplus of 2.6% of GDP (2018), while foreign currency savings in the National Wealth Fund (NWF) and on government accounts at the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) reached $133 billion by the end of September 2019 (nearly 8% of GDP).

Source: Ministry of Finance, Rosstat (Russian Statistics Agency)

“e” – estimates of the Ministry of Finance as of October 1, 2019; “f” – 2020-2022 draft budget

By mid-2019, Russia had made a rare achievement among its emerging market peers: public debt was fully covered by public savings. In other words, Russia has no net public debt.

However, the government’s obvious successes in terms of public finance are not being translated into economic growth. According to forecasts by international rating agencies, economic institutions and Russia’s government itself, GDP growth in 2019 will reach only 1-1.3%, while potential growth will range from 1.5-2% – inexcusably low for an emerging market.

One possible response is counter-cyclical policy, i.e. increasing spending in order to boost economic growth. Some Russian experts advocate (only verbally, without practical steps) such a Keynesian economic incentive; they suggest the budget deficit could safely reach 2-3% of GDP. But this is not possible as long as a fiscal rule based on strict correlation between expenditure and revenues is in place.

The budget in nominal and real terms

Still, the Ministry of Finance says the new budget will create economic incentives: ‘Due to completion of the period of budget consolidation in 2018 we could switch to fiscal stimulus as early as 2019,’ the ministry says, despite a planned budget surplus over the entire three-year period.

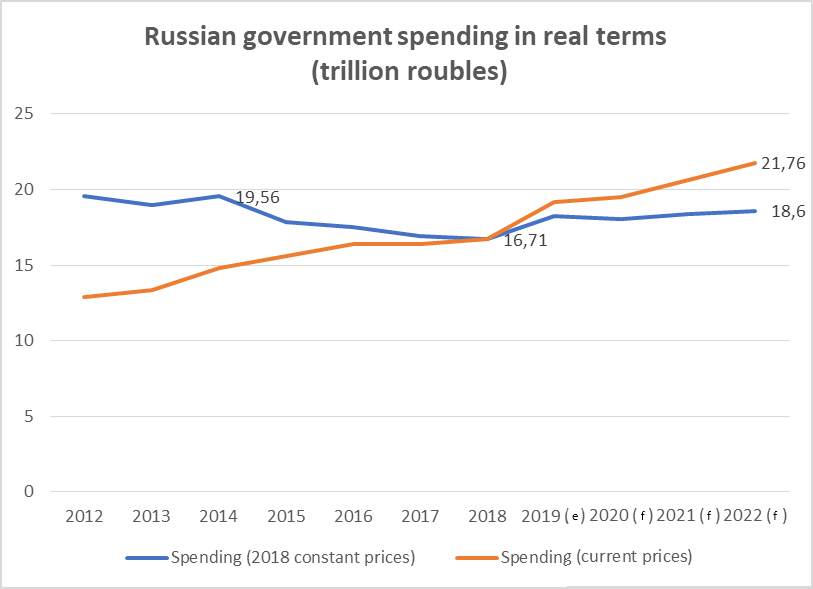

The ministry stressed that ‘Federal budget spending will increase during the next three years’. This is certainly true of nominal spending, which will grow by 1.9% in 2020 (compared to estimated 2019 spending), by 5.8% in 2021 (versus 2020) and by 5.5% in 2022 (versus 2021). However, the Ministry of Finance does not mention that there has hardly ever been a year in Russian history when spending in nominal rouble terms actually fell. And this is due to inflation, even though it recently dropped to 3-4%. Still, budget spending is depreciating every year.

In order to get an answer to the question: ‘How is the Russian budget changing in real terms?’ we estimated revenues and expenditure, taking inflation into account, and converted them into constant 2018 prices. The average annual consumer price index was used as a deflator (we used real data for the period before 2018 and estimates by the Ministry of Economic Development since 2019).

It turned out that when expressed in constant prices, federal spending will only increase by 3.2% by 2022 compared to 2020. In real terms, government spending will grow more slowly than Russian GDP over a period of three years: 3.2% versus 8.2% according to the base forecast of the Ministry of Economic Development, or 5.4% according to the conservative forecast.

Source: Ministry of Finance of Russia, author’s own estimates (annual average inflation used as a deflator)

“e” – estimates of the Ministry of Finance as of October 1, 2019; “f” – 2020-2022 draft budget

In other words, government spending in real terms will not catch up with the rate of GDP growth even under the pessimistic growth scenario. By 2022, spending in real terms will be almost 5% below the 2014 level.

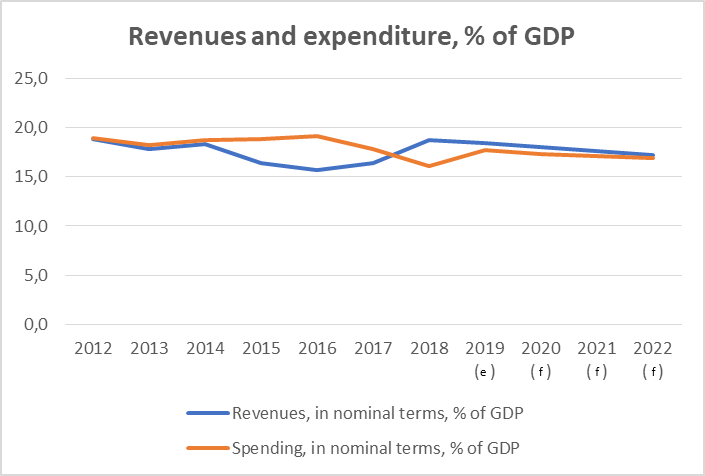

Similarly, as a percentage of GDP, nominal spending of the federal budget will consistently decrease over the next three years: from 17.7% in 2019 to 16.9% by 2022. To compare, in 2012-2016 government spending accounted for 18-19% of GDP annually.

Source: Ministry of Finance of Russia, Rosstat

To put it mildly, it turns out there is no significant increase in fiscal economic incentives from the point of view of total government spending. Recall that government spending in Russia (as a percentage of GDP) is much lower than in OECD countries.

Government spending limited by a fiscal rule

The government’s capacity to raise spending is limited by the tight fiscal rule which has been in force since 2018: total spending cannot exceed the sum of the following four components:

– base oil and gas revenues (oil revenues at a price of $41.6 per barrel in 2019 plus 2% per annum);

– non-oil and gas revenues;

– debt servicing costs;

– 0.5% of GDP.

The authorities loosened the fiscal rule in 2019 to add the fourth component (approximately 600 bn roubles).

Revenues from sales at oil prices exceeding $41.6 per barrel (in 2019) cannot be allocated to operating expenses and are transferred to a sovereign wealth fund. Currently, Russian oil sells for about $60 a barrel. In other words, even given these relatively low prices, about a third of the price of each barrel goes to the reserves. Since early 2018, 43% of all oil and gas revenues, or nearly $100 bn at the current exchange rate, has been allocated to the reserves.

The structure of the fiscal rule indicates that the Ministry of Finance perceives the fiscal incentive as mainly determined by growing non-oil and gas revenues. The expected growth of non-oil and gas revenues in 2020-2022 is largely associated with an elevated tax burden on businesses and consumers which includes the recent increase of the VAT rate and greater focus on tax collection (including VAT and payroll taxes). In other words, the government gives a fiscal incentive with one hand and partially takes it away with the other.

This is why the International Monetary Fund considers Russia’s current fiscal policy-neutral and not stimulating, as the Ministry of Finance would like to see it.

Are there incentives in terms of the structure of public spending?

An increase in the total volume of public spending in real terms does not necessarily indicate stimulating fiscal policy; the qualitative composition of expenditure is also important. Dmitry Kulikov, a macro analyst from the ACRA Analytical Credit Rating Agency, told me: ‘Different categories of expenditure have different fiscal multipliers. Therefore, a different composition of the same volume of spending will have a different stimulating effect’.

Fiscal multipliers show how GDP changes depending on the amount of government spending: e.g. if an increase in spending by 1% of GDP is correlated with economic growth of 0.5%, the multiplier is 0.5.

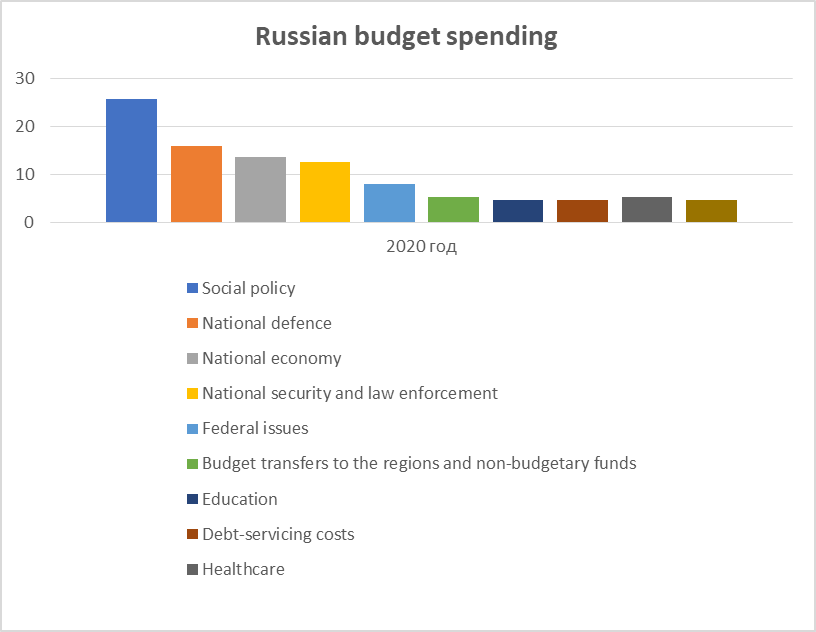

Unfortunately, there are no reliable multipliers for Russian government spending. Moreover, such categories of public spending as social policy (the largest category within the budget classification in Russia) include diverse spending items whose multipliers probably vary widely. Nevertheless, in general, it can be argued that the composition of the Russian budget is quite inert. For example, spending on state administration will remain almost unchanged at 8% for the next three years while the share of spending on defence and security decreases only slightly (from 28.5% to 28.1%).

Last year, CBR analysts estimated that spending on state administration had a negative multiplier (-0.73), while spending on defence and security, as well as social policy, had low although positive multipliers (0.32 and 0.28, respectively). Social expenditure traditionally has the largest share in the Russian budget (23-25% of all spending in the next three years).

‘There are no significant changes in the functional composition of federal budget spending for 2020-2022 (…) there are not enough new incentives for economic growth’, Chairman of the Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation and former Minister of Finance Alexei Kudrin states in his expert opinion on the draft budget. The same thesis is put forward more bluntly by economists from leading academic institutions ranging from the National Research University Higher School of Economics (НИУ ВШЭ) to Moscow State University (МГУ). Fiscal policy ‘is in fact aimed at preserving the existing structure of the Russian economy’, there are no active stimulating measures of economic policy envisaged while the budget is in line with the traditional ‘stabilising’ paradigm of recent times, says Alexander Auzan, dean of the Faculty of Economics at Moscow State University.

National projects delayed

Still, some incentives are foreseen in the draft budget: the share of expenditure under the National Economy section will increase from 13.5% in 2020 to 15.7% in 2022. This is primarily due to the implementation of so-called national projects (in the field of economics) including a comprehensive development plan for major infrastructure. The authorities are allocating 1.4 trillion roubles ($22 bn) for the next three years to build roads and railways, bridges, ports and airports.

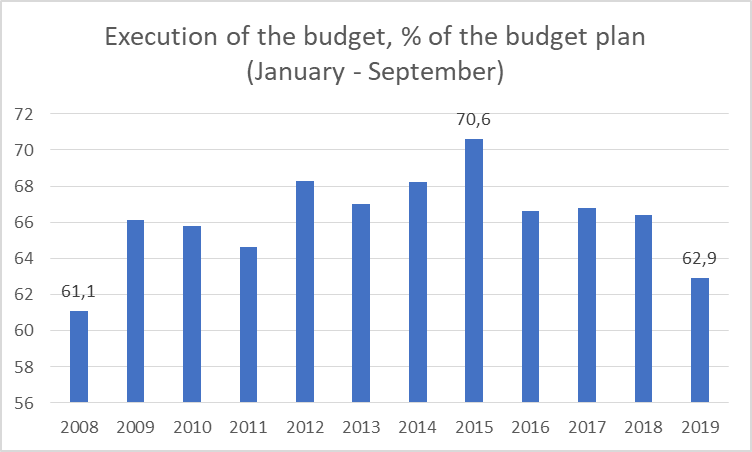

However, the parameters of national projects laid down on paper will probably not be fully met. The fact of the matter is that the new budget is compiled against the backdrop of the historically low execution of the 2019 budget. One of the main reasons is insufficient spending on national projects. During the first nine months of 2019 the government executed only 62.9% of its revised budgetary spending plan for the year – the lowest level since 2008. National projects were executed only at the level of 52.5% during this period. The CBR has admitted that insufficient budget spending in the first half of the year had a negative effect on economic growth.

Source: Ministry of Finance

Another potential incentive is associated with investments financed from the NWF: when the liquid portion of the fund (currency on CBR accounts) exceeds 7% of GDP, surpluses can be directed to projects within the country, i.e. some of the oil and gas revenues accumulated in previous years will be returned to economy. Formally, these investments in future infrastructure projects will not affect the parameters of the federal budget in any way since we are speaking of transfers of NWF assets from one form to another. From a functional point of view, these investments resemble additional budget spending. However, these will not be huge sums: annual NWF investments will constitute 15-20% of the excess over 7% of GDP (approximately 400 bn roubles or $6.3 bn in 2020).