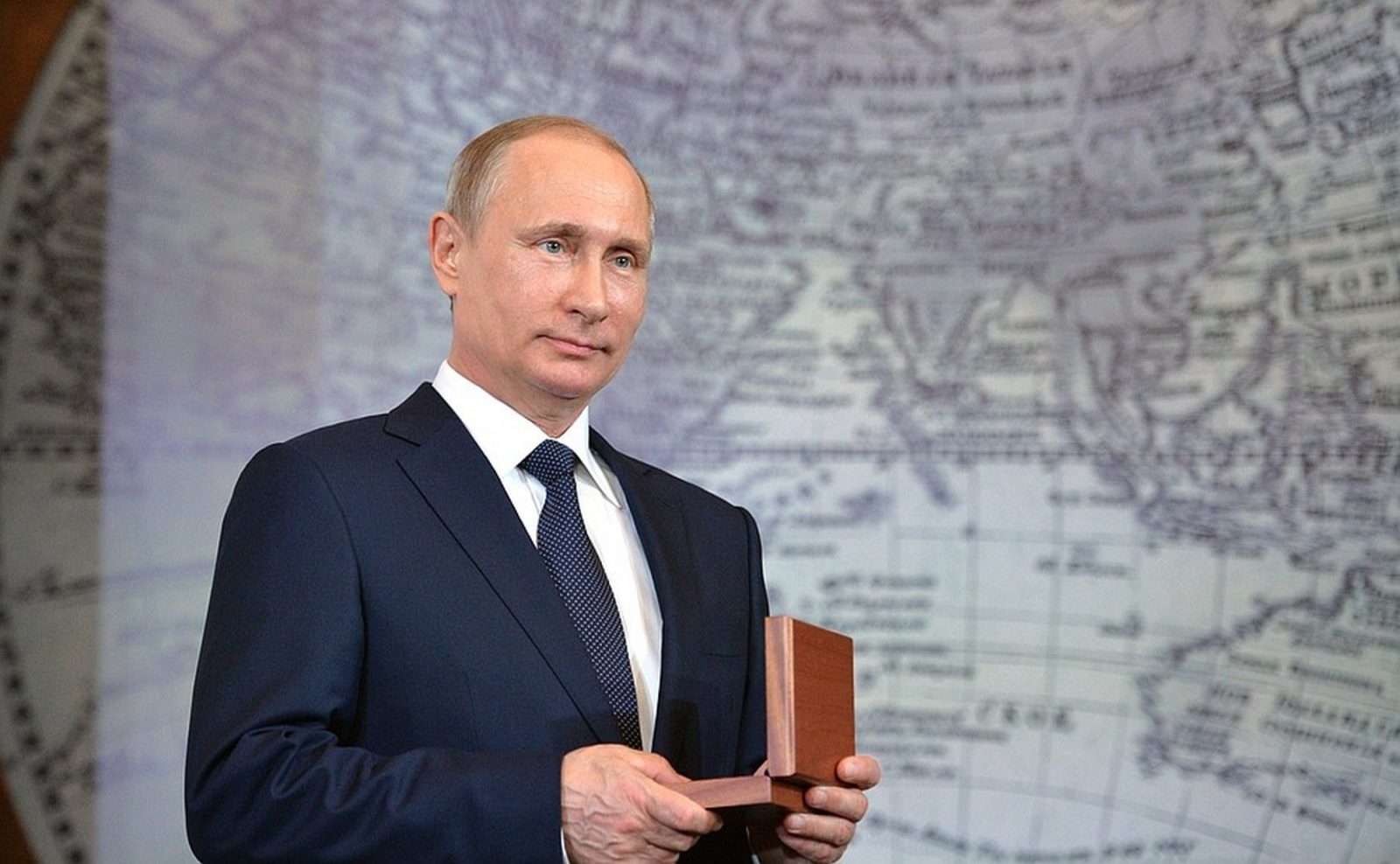

At the grand reopening of the Russian Geographical Society in 2009, then-Prime Minister Vladimir Putin explicitly linked the greatness of Russia as a state and as a culture to the size of its territory: “When we say great, a great country, a great state—certainly, size (or expanse, mashtab) matters.” This assumed link between size and relevance illustrates in an exemplary manner the idea, common in Russia, that the destiny of the country is linked to its geographic scope. According to Putin’s logic, it is impossible for Russia—as a country whose territory covers one-sixth of the Earth’s surface and extends from the heart of Europe to the Pacific Ocean, from the Arctic Ocean to the Kazakh steppes and the subtropical shores of the Black Sea—to be a power without influence on the international stage or a culture without global reach.

The Russian regime has been kept busy—if not always consistent—creating a new identity language and rebuilding a national discourse that makes sense of Russia’s history and current situation. If history, and especially historical continuity, are conventionally seen as the cornerstone of nationhood narratives, space also plays a central role in Russia’s national image and rebranding, for both domestic and international audiences. The celebration of Russia’s geographical scope, its incredibly diverse landscapes, and its wilderness have become routine for political elites—Putin’s personal involvement in extreme outdoor sports and his cross-country journey behind the wheel of a Lada in 2010 (at a time he was prime minister) confirm the heavy symbolism with which Russia’s spatial features are imbued.

The mission of reaffirming Russia’s territory and valorizing its geographical size has been given to the Russian Geographical Society (RGO). For the past decade, this imperial-era institution (established by Nicholas I in 1845) has been totally rebranded and modernized following a model clearly inspired by the National Geographic Society. The RGO has quickly become a very influential institution: its generous funding supports a wide range of seminars (around 300 in 2017 alone), exhibitions (around 100 per year), expeditions (around 3,000 since 2009), and book publications (around 5,000 since 2009). This activism is made possible thanks to the Society’s unique leadership: the Society boasts Putin as Chairman of the Board of Trustees (the Russian president speaks at the Society at least once a year) and Sergei Shoigu, Minister of Defense, as its president. For its part, the Board of Trustees brings together about a dozen oligarchs and the main representatives of the Presidential Administration—a revealing sign of the political nature of this renewed passion for geography.

In recent years, federal and regional leaders have primarily preferred to promote Russia’s territory through the fashion for big exhibition parks—likewise a Western trend that Russia has rapidly made its own, but which has also become a trademark of rising Asian and Middle Eastern powers, with Singapore and Dubai at the vanguard. Nor does Russia exclusively borrow from abroad: it can also draw on the Soviet gigantism tradition of exhibition parks displaying national achievements, such as VDnKh.

The “wild nature festival” of the Golden Turtle (Zolotaia cherepakha) is a pioneering example: launched in 2006, it promotes awareness of nature and ecology through art projects (mostly photo and painting awards), with more than 100,000 projects submitted over the course of a decade, and annual exhibitions in several Russian cities. Awareness of nature and biodiversity is understood as part of the “patriotic education and improvement of Russia’s image in the international community.” Another example is Pristine Russia (Pervozdannaia Rossia), an annual exhibition funded via presidential grant that celebrates Russia’s nature. The exhibition takes visitors on a virtual tour of the country’s national parks and protected areas, and follows animal life through state-of-the-art animal documentary films and photos.

In Moscow, a permanent park, Zaryadye Park, recently emerged in place of the former Rossiya hotel, between Red Square and the Moskva River. A new cultural attraction with a glass bridge over the river, the Park is divided into four landscape zones representing Russia’s varied climate and diverse territories (forest, steppe, meadow, northern landscapes). Besides a sample of regional flora and fauna, it features educational and recreational places such as a greenhouse florarium, an ice cave, a concert hall, and a cinema with a panoramic screen. The park allows Russia to display its mastery of new, green technologies such as drainage systems for collecting rainwater, automatic drip irrigation, and vacuum debris removal, as well as confirming the extraordinary rethinking of urban landscape and public spaces currently underway in Russia’s megalopolises.

But the Russian state is pursuing a much more ambitious goal: “Park Rossiia.” This theme park, devoted to the nature, traditions, and cultural heritage of all the regions of Russia, should have combined the model of Singapore’s Gardens by the Bay—a 100-ha garden in the middle of the city—with Orlando-style attraction parks. The initiative to build the park was put forward in 2012 by the RGO in the person of its president, Sergei Shoigu, who at that time also held the position of governor of the Moscow region. It was planned that the construction of the facility from scratch will take about 10 years and will cost $ 8 billion. However, in 2016 it became known that the Moscow region was unable to find investors and was forced to abandon the construction of “Park Russia”.

If realized, the Rossiya Park could find itself in competition with another project, that of a Russian Disneyland. Evoked under Khrushchev and Brezhnev, but never realized, it was relaunched by then-mayor of Moscow Yuri Luzhkov in the 2000s, again meeting with failure. The project, called “Dream Island” (Ostrov mechty), has been reactivated by current mayor Sergey Sobyanin and is currently under construction in one of Moscow’s suburbs, Nagatino, with an official opening planned for 2019. It will celebrate the rich Soviet tradition of animated films and of Russian tales.

The long-term trend of rebranding Russia’s territory accelerated in 2017, designated “year of ecology.” A new law on the status of protected territories (okhraniaemye territorii) and nature reserves (zapovedniki) was enacted, with the creation of several new national parks in Karachaevo-Cherkessiia, Kamtchatka, Krasnoyarsk krai, and the Yamalo-Nenets autonomous district. But these welcome decisions cannot hide one of Russia’s critical ambivalences: if the country’s greatest legacy to the planet is its role in biodiversity and wilderness preservation, it has failed to advance effective environmental legislation and has gradually lowered the status of environmental protection. In this bleak picture, a notable exception has been the expansion of the protected area system—an easy way to “green” Russia’s policy, as it protects some territories from human exploitation without any compulsion to address the energy inefficiency and pollution of the country’s industries. The numerous exhibitions honoring Russia’s unique nature, too, avoid discussing the dysfunction of the country’s environmental policies.

The emphasis placed on Russia’s territories reflects the authorities’ willingness to address the country’s infrastructure challenges. Putin’s long tenure has been marked by profound changes in the spatial organization of the territory: as analyzed by the geographer Jean Radvanyi, measures have been taken to modernize infrastructure and develop the most sensitive and strategic regions, but a more sophisticated regional strategy is needed and the concrete inequalities between regions in terms of transport infrastructure and accessibility may threaten or at least weaken the very unity of the country. Many of the exhibitions discussed here praise not only Russia’s nature, but also the infrastructure projects that allow for regions to develop: the Kerch bridge to Crimea, the Vladivostok bridge, the repair of airports and roads, etc. They contribute to promoting these costly infrastructure projects in the eyes of public opinion and securing consensus around the regime’s approach to addressing territorial and logistical issues.

This craze for honoring Russia’s territory and its landmarks also underlines a geopolitical goal, that of loudly reaffirming the country’s legitimate place in the concert of nations. While Moscow struggles to keep its superpower status from declining further—the Russian economy represents less than 2% of global GDP and its military spending is about one-tenth that of the US—the use of superlatives, a symbol of a superpower status, has been restricted to spatial features: Russia remains the largest country in the world. The current “decolonizing” fights of former Soviet republics—which seek to cast off Russia’s historical domination by changing their historical topographical names, national heroes, and sometimes alphabets—accentuate the impression that Russia’s global relevance is collapsing. To resist this trend, Putin decided, in April 2018, to commission a new atlas of the world that would re-establish “historical and geographical truth” (istoricheskaia i geograficheskaia pravda). Not only will the Western names given to some remote Russian territories be russified—the president explicitly mentioned that some Siberian and Arctic territories had been given the name of a famous Western explorer when they already had a Russian name—but one can guess that the atlas will also fight against the “derussification” of names backed by Russia’s neighbors in the post-Soviet space as a whole.