About fifteen years ago, when President Putin’s geopolitical plans were still at the incubation stage, developments in the Russian market economy were bringing almost unthinkable profits to the ‘shock workers of capitalist labour’. Forbes 2008 ranking of dollar billionaires included 87 Russians (out of the total of 1,125 people), with four of them in the Top 20 of the global ‘table of ranks’. The acquired property—as Western liberals claimed—was expressed through freedom. The press was full of reports about the chateaus, planes, yachts and works of art those billionaires bought, and their the unbridled revelry in Courchevel or parties in London. The ‘New Russians’ were also the youngest cohort of the global business elite: their average age was 46. However, Russia, which ‘has risen from its knees’, tossed its former idols in the mud after a fairly short time: today, the wealthiest Russian comes 87th in the global ranking, and the combined wealth of the 20 wealthiest Russians falls substantially behind the wealth held by Elon Musk alone. However, most importantly, ownership of property has brought serfdom rather than freedom to all the super-rich Russians: they mistakenly considered themselves to be part of the global jet set. Nowadays, in the eyes of the West, they are citizens of a criminal country and accomplices of its fascist leader, which is why they are losing foreign assets en masse and are forced to move back to Russia.

The war in Ukraine and sanctions against the wealthiest Russians have resulted in huge financial losses (according to some estimates, the value of their assets has shrunk by even USD 54bn, while the amount of frozen assets and seized property in foreign jurisdictions stands at USD 30−35bn). (In this context, we can mention, in particular, the loss of such expensive items as the USD 440 million Sailing Yacht A and the $ 300 million Amadea owned by A. Melnichenko and S. Kerimov respectively). More importantly, however, the property that still remains in their hands has acquired a new status.

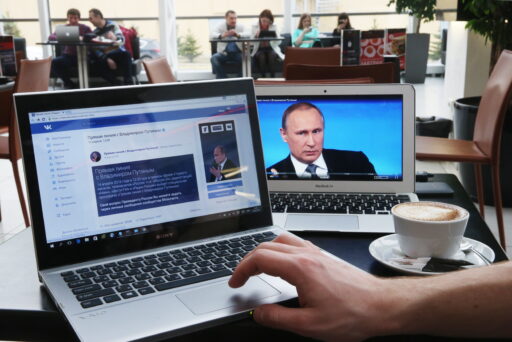

It should be noted that Russian business has understood the consequences of Putin’s war quickly and correctly. As leading Russian businessmen were respectfully listening to the President in the Kremlin on the evening of 24 February, their private jets were warming their engines up in the Vnukovo‑3 airport. However, the swift exodus was short-lived (according to various sources, almost half of the Forbes Club members left Russia in the first 48 hours after the start of hostilities against Ukraine ): in the months that followed, at least 70 Russian billionaires (including all members of the ill-fated meeting between the President and leading members of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs) found themselves under EU, US and UK sanctions and some, such as A. Rotenberg, K. Malofeev, A. Miller and A. Akimov, have been on the ‘stop lists’ since 2014−2016. And even though the inclusion on the sanctions lists did not lead to deportation (some Russians are still living in the jurisdictions that put them on those lists, e.g. M. Fridman in the UK), major businessmen quickly realised that their assets in the West did not represent the majority of their wealth, and, on the other hand, very rarely generated steady income. This is why, starting from April and May 2022, the ‘relocated people’, faced with an uninspiring perspective of ‘gulping the dust’ in European courts, have been returning to Russia to sort out their business and to keep competitors out of budgetary streams and public procurement deals.

As a result, one year after the outbreak of war, we can state that Putin has ‘nationalised the elites’ more successfully in the past twelve months than in the preceding eleven years. We can identify three ‘groups of comrades’ by their location and behaviour and cannot but conclude that Russian business has proved to be a no less solid foundation for the regime than, for example, the security forces, with loyalty being based on the ‘feeding hand’ in both cases.

The main (and by far the largest) group comprises those who quickly ‘realised’ the malignancy of their fascination with Europe. If we take the 2021 Forbes list as a reference point, we will see that around 40−50 of the top 100 people are staying within Russia nowadays. They continue to ‘work constructively’ in the country, although many of them have left their posts as managers or board members of their companies since their formal participation in asset management makes the business of their respective companies very difficult (this factor can be ignored only by openly criminalised businesses, such as A. Tkachev’s Agrokomplex; the latter does not even shy away from seizing land in the occupied regions of Ukraine). Some of these entrepreneurs hastily got rid of a significant proportion of their assets by transferring them to their children (like R. Abramovich) or wives (like V. Mordashov, head of Severstal, and D. Melnichenko, head of EuroChem), or by announcing ‘retirement’ (as A. Usmanov did, to observers’ surprise). However, one can confidently assert that Russia’s business elites have been radically ‘nationalised’ now: the share of their assets located in the Russian Federation has gone up, increasing their dependence on the country’s authorities. Many people, with V. Potanin being the leader here, have been actively involved in buying up the assets of foreign companies that have left Russia, while arguing how wretched the confiscation was. Most businessmen, meanwhile, are passively watching the developments, meekly pay the rising taxes, visibly participating in import-substitution programmes and working in all sorts of commissions to support economic sustainability in wartime. Now, the South has become an alternative to the West: wealthy Russians are buying up property in United Arab Emirates, Israel and Turkey, but no longer set their sights on foreign countries as a primary place of residence (even the long-time resident of Switzerland and newly minted UAE citizen D. Melnichenko has recently returned to Moscow).

Nevertheless, some businessmen, even the richest ones, have chosen to leave the country while preserving Russian assets, keeping quiet about the events in their homeland and, most importantly, keeping the public information of their whereabouts at a minimum. Among them is, for example, M. Prokhorov, who departed for an unknown destination after the start of the war, probably managed to obtain an Israeli passport, following which news of him has practically dried up. That said, it is important to note that this former presidential candidate remains Russia’s richest citizen, not subject to any sanctions, and his beautiful yacht, the Palladium, has lately been sailing various between ports on the west coast of Central America. A similar tactic has been applied by many less significant businessmen who have not been put on the European or US sanctions lists and now prefer to spend most of their time abroad, in complete loyalty to the Russian authorities. At the same time, this group of businessmen is constantly at risk of sanctions, as Ukraine has included all Russians from Forbes list into its lists, including not only M. Prokhorov, but also R. Abramovich, who participated in the negotiations with Russia, seizing and confiscating the assets of many businessmen who have not faced any claims from Western countries. For example, the construction materials production facilities have been built from scratch in recent years by the Russian LSR group, controlled by A. Molchanov. Kyiv, on the other hand, constantly urges the West to use the sanctions lists compiled by Ukraine, which are more extensive than any other lists at the moment.

Finally, the third group, very small at that, includes entrepreneurs who have decided not to return to Russia, even though they own large businesses in the country. Among them, not surprisingly, are the owners of Alfa Group, M. Fridman and P. Aven. Several years ago, Forbes called Alfa to be the most ‘internationalised’ Russian financial group, based on the extremely high share of foreign assets in the total wealth of its beneficiaries. For various reasons, some people are quite openly living outside Russia, among them O. Tinkoff, the founder and former owner of Tinkoff Bank, G. Volozh, a major shareholder in Yandex, and A. Mamut, owner of a diversified asset portfolio (we can also add A. Usmanov, who has now settled in Tashkent). Some businessmen, including Yu. Milner and N. Storonsky, have even renounced their Russian citizenship. Many of these businessmen are under Western sanctions, and they are all striving to challenge sanctions decisions and have been involved in ongoing litigation with the European authorities, attempting to prove their non-involvement in Russian aggression (which the Kremlin is unlikely to be enthusiastic about). Notably, even though many oligarchs have returned to Russia, more than 60 people are suing the European authorities over the personal sanctions that have been imposed on them, and, according to European lawyers, many of these lawsuits are not hopeless.

According to rough estimates, entrepreneurs who accounted for less than 10% of the assets cumulatively controlled by Russian billionaires when the war started in Ukraine, have physically left Russia for the long term over the course of 2022. This is because in a country not based on the rule of law, property becomes the foundation of serfdom rather than freedom: having spent years building business empires, people become hostages to them, and are prepared to go to great lengths to preserve what they have accumulated. The Kremlin is now brilliantly using this lever to defeat even the most unshakable tenets of economic liberalism in its policies. Moreover, the sanctions policy pursued by Western countries cannot be neglected as it has helped to ‘squeeze out’ the oligarchs back into Russia, and their assets have been massively re-registered from foreign jurisdictions to their homeland. The sanctions, based on how they were imposed, have helped to consolidate Russian business around the Kremlin and particularly punish those who, for many years, have sought to conform to Western standards of business transparency while they have not affected the ‘autochthonous’ Russian thugs who are also in substantial contradiction with the basic tenets of the Western legal system. The rule of law is based on the assumption that the law must have universal validity, which is why sanctions against individual countries, industries and/or export and import positions are fully acceptable, while restrictive measures against specific individuals cannot be imposed except by court decision, with all the elements of adversarial prosecution and defence (in contrast, sanction measures are introduced by the executive branch of power, i.e. not even by parliaments). In other words, I would venture to say that two voluntaristic systems have collided, oddly enough, in the field of personal sanctions against Russian entrepreneurs and the conflict resulted in the ‘repatriation’ of businesses into their original environment.

The last question that often comes up when assessing the fates of the Russian business elites is whether they might try to regain their long lost political power in Russia (after all, everyone remembers how entrepreneurs often rules to the Kremlin in the ‘turbulent 1990s’). I would say that despite demonstrating full loyalty to Vladimir Putin, large Russian businesses will never forgive him the ordeal that they had to undergo in recent years. Huge efforts undertaken to ensure integration into the international business environment turned out to be in vain. The hopes that Russian assets could be protected by staying in Western jurisdictions have been dashed. At the moment, none of the big businessmen is ready to condemn Putin’s policy actively (it is noteworthy that O. Deripaska, M. Fridman and D. Melnichenko have criticised the war during its first weeks, while only O. Tinkov has spoken out against the aggression more consistently). However, if the regime turns out to be unstable, it is doubtful whether business will be able to consolidate against the security forces (siloviki) and the turbo-patriots, and provide genuine support for politicians who are more tolerant of the outside world (whether Alexei Navalny or others). In other words, the business world could give a push to the pendulum which has been moving Russia between isolationism and openness to the world for almost two centuries by swinging it towards a new collaboration with the West. And, obviously, this will not happen tomorrow.