It’s easy to forget that, in a country of 140 million, there are still millions of people who — some openly, most quietly — do not support the war and are broadly skeptical of the current authoritarian regime. Even without deep ethnographic immersion, regular large-scale survey data are sufficient to identify several quite substantial clusters of war opponents with confidence.

The anti-war field

The «Chronicles» project has been consistently tracking two poles: staunch supporters and staunch opponents of the war in Ukraine. The classification rests on three core questions:

- Attitude toward the war;

- Budget priority (defense spending vs. social spending);

- Support for a hypothetical decision by Vladimir Putin to withdraw troops and start peace talks.

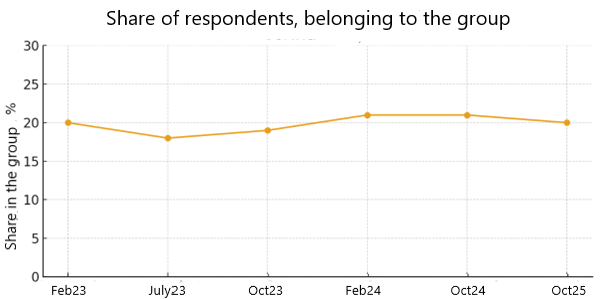

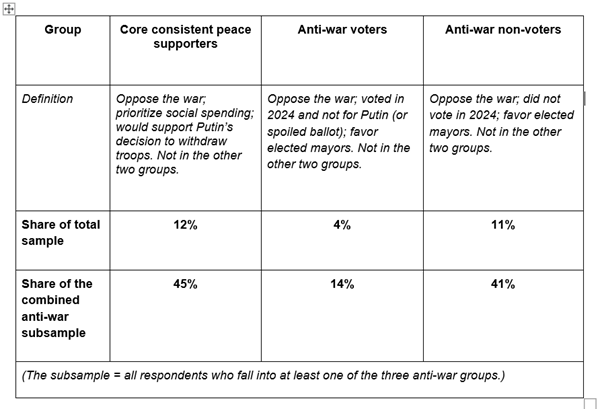

Respondents who would welcome troop withdrawal, prioritize social spending over military, and do not express clear support for the «special military operation» (i.e. say they do not support it, don’t know, or refuse to answer) are classified as consistent peace supporters. For almost two years, this group has hovered steadily at around 20% in Chronicles surveys.

Yet the real mobilizational potential of this 20% remains hard to gauge. How willing are these people to voice their opposition openly? To what extent do anti-war sentiments overlap with anti-Putin ones?

Data from the 14th wave of Chronicles (February 2025) contain a set of questions whose combination makes it possible to single out not only war opponents but active regime opponents. Three criteria were used:

- Negative attitude toward the war;

- Participation in the 2024 presidential election and voting for anyone except Vladimir Putin (another candidate or spoiling the ballot);

- Preference for elected rather than appointed mayors.

The resulting group — «anti-war voters» — amounts to just 4% of the total sample. Almost 80% of them fall inside the broader «consistent peace supporters» category, yet only 14% of the broader group display political activity and end up among the «anti-war voters». In other words, politically active war opponents are a small sliver of a much larger anti-war field whose majority consciously stays away from elections.

Attitudes toward the very concrete (rather than hypothetical) elections serve as a crucial marker of mobilization. Russia’s recent experience shows how difficult it is for regime critics to agree on a common tactic — from outright boycott to «smart voting». The 2024 presidential election under wartime conditions both confirmed this chronic problem and, paradoxically, revealed that a latent demand for conventional political resistance still exists and can be surprisingly strong (the short-lived campaigns of anti-war candidates Yekaterina Duntsova and Boris Nadezhdin and the unexpectedly massive public response they triggered).

Another identifiable segment consists of people who oppose the «SMO», favor elected mayors, and did not vote in the 2024 presidential election. This «anti-war non-voters» group makes up 11% of the sample.

By design, the two latter segments do not overlap: one expresses anti-war stance through electoral participation and protest voting, the other through complete abstention. Together they account for roughly 15% of respondents.

Three faces of Russia’s anti-war camp

Let us examine the similarities and differences among three distinct anti-war segments in Russian society, focusing on their internal characteristics. In terms of age structure, the groups are broadly similar, yet clear accents emerge.

The «anti-war voters» stand out for their high share of middle-aged respondents: almost a third (31%) are aged 40−49, while young people aged 18−29 make up only 15%.

The «anti-war non-voters» are noticeably younger: half are under 30, and the proportion of forty-somethings is well below average (16%).

The «narrow core of consistent peace supporters» is the most evenly distributed: 24% in each of the two youngest cohorts, 19% aged 40−49, and 15−19% in the older age brackets.

In other words, within the broader anti-war milieu younger people are more likely to reject electoral participation entirely, whereas middle-aged respondents tend to opt for protest voting. The differences are statistically significant but represent a soft trend rather than a sharp divide.

The contrasts become particularly striking when we look at how respondents perceive the war’s impact on their daily lives. In all three segments a majority believes that the so-called «special military operation» has affected them mostly negatively: around 69% in the narrow core and among non-voters, and nearly 90% among voters. Only 2−3% in each group report a positive impact. The key divergence lies in the share who say «nothing has changed.» In the narrow core and among non-voters roughly a quarter give this answer, whereas among the politically active anti-war voters who turned out the figure is only 6−7%. The difference is statistically significant. Thus, it is precisely the small group that bothers to vote against the regime that almost unanimously experiences the war as a direct and deeply negative personal event, while the broader anti-war field tends to treat its effects as background noise.

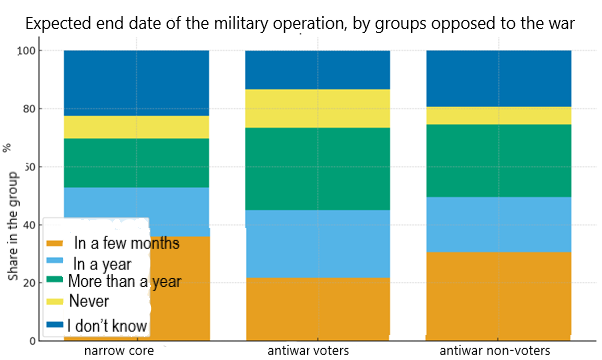

Expectations about the war’s duration also reveal clear divergences. Respondents in the narrow core are the most inclined to believe in a relatively swift end: 36% expect it to finish «in a few months,» and the share who think it will last «more than a year» or «never end» is below average. At the same time, they have the highest proportion of «don’t know» responses (23%). The anti-war voters are markedly more pessimistic: only 22% choose «a few months,» while 28% expect it to drag on «more than a year» and 13% believe it will «never end.» The non-voters occupy an intermediate position: closer to the narrow core in their expectations but with fewer extreme pessimists. The pattern is clear: it is the politically engaged opponents of the war, those who vote, who most often see the conflict as protracted and almost hopeless, whereas the others either cling to cautious hope for a relatively quick resolution or prefer not to hazard a forecast at all.

Data from the 14th wave of the «Chronicles» survey reveal an intriguing Soviet legacy in the political behavior of Russia’s anti-war citizens. Overall, about a third (33%) of war opponents report that their relatives experienced repression or dispossession under Soviet rule — virtually identical to the sample average (32%). The figures are close to this level in the narrow core (29%) and among non-voters (31%). But among anti-war voters the share with family memories of Soviet terror is markedly higher — 44%. The difference is statistically significant: those willing to cast a protest vote are substantially more likely to carry an inherited trauma from the Soviet terror.

It is also worth noting how the three groups differ in everyday civic and social practices. The baseline picture is quite similar: 8−10% in each segment say they helped no one over the past year, while a majority primarily assist friends, acquaintances, animals or charitable causes (over half in every group). Distinct patterns emerge, however, once the war enters the equation. The narrow core and non-voters are considerably more likely to have helped the army (30% and 26% respectively) and much less likely to have aided refugees (9% and 6%). Among the active anti-war voters the mirror image prevails: help to the military is rarer (15%), while assistance to refugees is one-and-a-half to two times more common (17%).

Thus, one part of the anti-war public not only opposes the war politically but also shifts real-world help away from the army and toward the conflict’s victims. Another part, despite holding anti-war convictions, remains embedded in the dominant practice of supporting the troops. At first glance this looks contradictory, yet different motives may lie behind it — from a desire to give a socially approved answer to a genuine distinction between «the war as policy» and «soldiers as concrete individuals, often personally known.» In the latter case helping the army is framed as support for people, not for the institution itself.

The anti-war voters appear the most consistent: they vote against the regime and direct their help toward victims rather than the military. By contrast, the narrow core and especially the non-voters more often remain anti-war in words only; their beliefs rarely translate into actual political or civic action.

Differences in experience and intensity of participation in civic associations are also revealing — and here the gaps are statistically significant. Low engagement (membership in one to three organizations) dominates across the board: around half in the narrow core and among voters, roughly 40% among non-voters. Yet the non-voters stand out for their high share of complete isolation — almost half belong to no civic association at all (versus 35% in the narrow core and 39% among voters). High engagement (four or more organizations) is rare but noticeably more common among voters and the narrow core than among non-voters. Those who boycott elections are also far more likely to stay outside any civic networks altogether, whereas members of the narrow core and voting opponents are at least plugged into one or two institutional settings — trade unions, housing cooperatives, volunteer groups, environmental initiatives, etc.

Perhaps the starkest distinction lies in electoral behavior itself. Across the full sample a quarter of respondents did not turn out.

- In the narrow core slightly more than half openly admit voting for Vladimir Putin. Another quarter declined to answer, while a minority split between the remaining candidates or spoilt their ballots.

- The anti-war non-voters, by definition, boycotted the election.

- The anti-war voters present an almost perfect mirror image: roughly 22% in total backed Nikolai Kharitonov and Leonid Slutsky, 25% spoilt their ballots, and more than half say they voted for Vladislav Davankov.

Taken together, the picture is sobering: almost half of all anti-war respondents stay away from the polls entirely, another quarter vote for Putin, and only a minority use the ballot as an instrument of conventional protest. Yet herein lies considerable untapped potential for electoral coordination. After Boris Nadezhdin was barred from running, the Russian opposition failed to agree on a common strategy. Even so, the systemic candidate Davankov — who signaled his anti-war leanings only obliquely — became a focal point for those wishing to express their attitude toward the war and the regime through action. This suggests that, given a coordinating actor, the anti-war and anti-regime electorate is capable of rapid and effective consolidation. Such a force may not drive the final nail into the coffin of Russian authoritarianism, but it would certainly become a serious problem for it.

The landscape of war opposition in Russia turns out to be far more complex than it first appears. It is not a single «anti-war bloc» but several clusters of people united by rejection of the war yet divided by how they respond to political reality. The smallest yet most principled and consistent segment is the active anti-war voters. They are the ones prepared to tell a telephone pollster outright that they oppose the war, support democratic principles and openly favor a change of power. To much of society, and even to some of their fellow anti-war countrymen, these people probably look odd: after all, turning up to vote is still «playing by the regime’s rules.» Yet in their behavior one can discern a stubborn determination to exploit whatever narrow channel exists to register protest against the war and the system. And most importantly — the growth potential of precisely this group is very far from exhausted.