While Russian officials squander a chance to negotiate an end to the war in Turkey, the regime’s collective confidence in its ability to sustain the conflict cannot be explained by its capacity to maintain war spending. Claiming the state can sustain funding at the war’s current intensity is both reasonable and absurd in its implications. Spending down the remaining liquid reserves in the National Welfare Fund buys time to defer issuing more debt—a significant concern since oil and gas revenues are down 24% against 2025 budget forecasts, the deficit is trending toward breaching the 2% GDP limit preferred by the Ministry of Finance (MinFin), and MinFin’s May 7 auction of OFZs failed to attract any bidders for Russian sovereign debt. These warning signs are alarming but manageable in the strictest sense: the state has ample means to raise funds, whether through loan subsidies, other interventions, or adopting novel measures like forcing the Bank of Russia to buy debt if necessary.

However, this logic collapses when considering the ostensible progress made since 2014 to increase non-oil and gas revenues and the broader forces unleashed by the war that are undermining the state’s ability to «stabilize» the economy. Official data pegs inflation at approximately 3.3% from January to mid-May—a significant improvement over rates twice as high in 2023−2024. Yet, this figure must be viewed in context. The Bank of Russia still maintains a key interest rate of 21%, high enough to render countless investments unviable due to the sky-high hurdle rates projects must meet to recoup costs for investors or cover debt service. Purchasing Managers’ Indices (PMIs) indicate declining manufacturing despite improved input prices from a stronger ruble, while services are approaching zero growth. Despite a more favorable environment for inflation, average household weekly spending in early May was 15.1% higher than in 2024.

Paradoxically, families are spending more while the consumer economy shows myriad signs of hitting a wall. The Union of Trade Centers (representing malls) reports a 30−35% decline in Q1 sales due to falling foot traffic and competition from cheaper online retailers—losses severe enough to put half of non-food retailers at risk of financial losses in 2025. Sales of agricultural equipment dropped 33% in Q1 due to high interest rates, a shocking outcome given that many agricultural producers rely on outdated equipment or capital goods acquired during the subsidy surge after 2014. New research reveals that since 2018, fast-growing companies—fewer than 2% of all firms in Russia—accounted for 50−61% of earnings growth in any given year. In other words, the market for nearly everything is stagnating unless businesses can sell to consumers more cheaply or exploit opportunities created by state policies. Consumers are pinching pennies so tightly that 50−70% of airline passengers, according to recent Kommersant surveys, forgo baggage fees and travel with only carry-on luggage. Cost-cutting is so rampant that turkey steaks accounted for 60% of the steak market for household consumers in 2024.

The challenges don’t end there. Far East cargo loadings on the rail network are down 3.7% year-on-year, a critical metric given the redirection of exports and the substitution of European imports with goods from China. On one hand, the government is aiding loss-making coal miners in Kuzbass and elsewhere by writing off taxes, restructuring or forgiving debts, and offering freight cost discounts via rail. On the other, MinFin has refused to extend a mere 14 billion rubles to Kemerovo oblast, the heart of coal country, forcing the regional government to borrow at a 23.9% interest rate from VTB. Sberbank and VTB are reportedly waiving commissions for housing projects they’ve financed for developers, at a time when state-supported projects account for 95% of VTB’s January-April portfolio—a clear sign that vast swaths of economic activity are unsustainable at current interest rates.

These indicators make a mockery of claims about the stability of wartime financing. The greatest success of Prime Minister Mishustin’s tax reforms from 2014−2020 was recouping a larger share of VAT taxes on consumption, paired with an increase in the base rate from 18% to 20%. Non-energy revenues—taxes on consumption, incomes, or profits—are cyclical, trending with GDP and the business cycle. However, the war has severed the link between GDP growth and the consumer economy’s business cycle, following an initial sugar high from signing bonuses and MinFin’s 2022 decision to allow 90% upfront payments for procurements to catalyze activity. If inflation remains above the 4% target despite such high interest rates, and with clear signals that consumers are battening down the hatches as real incomes stagnate, a growing share of the non-energy tax base is entering a trough. As the National Welfare Fund depletes, oil prices remain low, and the ruble strengthens, the trade-offs become far stickier.

The National Welfare Fund was intended to finance strategic import-substitution projects post-invasion. The recent failure of the Baikal turboprop aircraft—a humiliating setback for a government obsessed with projecting economic sovereignty—has led to promises of a working group to resolve the issue, while officials haggle over repairing and renewing existing Antonov aircraft. The Fund was meant to provide initial financing for such projects in 2023−24, but its capacity as a piggy bank is now tapped. Finance Minister Siluanov and other officials will face growing pressure in the second half of 2025 to cut spending, given that their much-touted success in reducing the budget’s dependence on energy revenues hinges on increasingly cyclical revenue sources.

This is not to say there’s a definitive point at which the war becomes financially unsustainable. Rather, the concept of «sustainability» has been stretched so thin by analyses overreacting to the mistaken assumptions of 2022 that it has lost meaningful utility. Labor remains the single greatest constraint on the war’s sustainability, not the numbers on spreadsheets. There are simply not enough workers to go around, and Mishustin’s influence over the Ministry of Industry and Trade is so pronounced that officials are discussing robots and automation to offset a deepening deficit of millions of needed laborers. Robots don’t pay taxes, and Russia’s labor institutions are designed to limit workers’ power to collectively bargain or demand concessions, with few exceptions. Moreover, the economics of investing in automation are dubious when businesses cannot predict future demand, and the steady stream of dead and wounded working-age men exiting the workforce—offset by cash payments that buy far less than they did in 2023 or 2024—continues to devastate regions outside Russia’s major metropolitan areas.

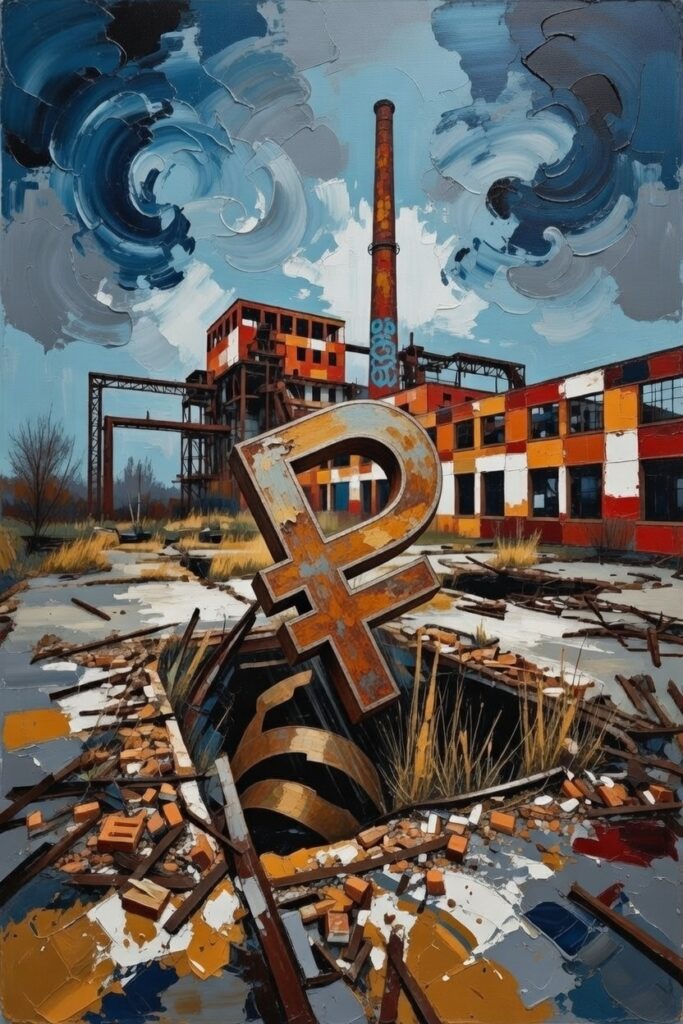

There is no longer a «sustainable» way to tame inflation without immiserating the country. This does not mean the regime cannot survive and continue absorbing immense casualties, relying on inaccurate, mass-weapons systems to offset a dwindling advantage in high-end gear against Ukraine. Calling the situation «sustainable» mistakes continuity for stability. The regime can keep fighting this war on its terms for the foreseeable future, but it is doing so with a tax base it is wrecking, in a country once again filled with aging or decrepit capital stock that cannot be renewed or replaced at current interest rates. Sadly, the demands made by business leaders to Putin on May 13 were small-minded, evidence that no one has the freedom to advocate for marginally logical policies that would enable the state to provide the public goods businesses need to thrive.

Waiting for an economic crisis to topple the regime is a fool’s errand. The economy now operates in a state of permanent crisis; the only question is who bears the daily costs of adjustment. For years, the state has metaphorically punched families in the face while insisting their lives were improving—a lie so cartoonish that officials now frame the slowdown as a natural and necessary corrective to their «reasonable» policies. Even the pockets of society that benefited from the war and sanctions are beginning to realize how fickle the state’s visible hand and the market’s invisible hand have become in a country burning its future with no thought for tomorrow.