Over the past six months, Alexei Navalny and his supporters have repeatedly backed Communist candidates. His local staff helped organise protests in favour of Communist candidates in Primorsky Krai and Khakassia. In August last year Navalny called for mass protests against the pension reform on September 9, the day of the combined elections. All these actions give food for thought: Is Russia’s main opposition leader ‘turning left’? And is there much of a voter base for leftist policies?

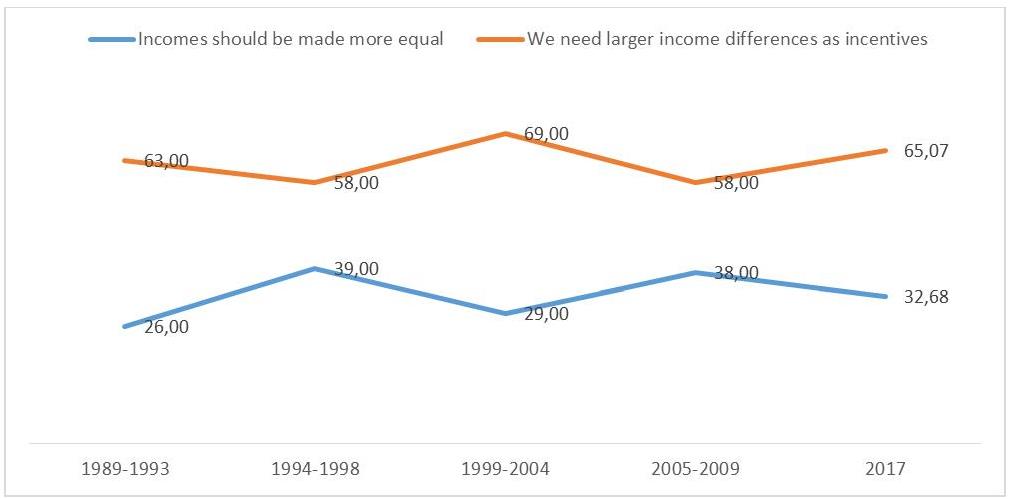

First, let’s define what we understand by leftist ideology. If we look at the generally accepted measures of leftism, the majority of international questionnaires contain questions about attitudes to redistribution, higher tax rates and economic equality in general. According to the World Values Survey, the share of those believing that incomes should be equal has risen in Russia since the early 1990s: It stood at 26% in the early 1990s and was 29% during the 1999 crisis. By 2006, the proportion had reached 38%, though by 2017 it was back to 33%. If we interpret the demand for leftist ideology in a narrow sense, as demand for greater economic equality, not much has changed much since the collapse of the USSR.

Compared to similar studies in Western European countries, Russian respondents are less inclined to support equality. Due to the diversity of structures of the welfare state in Europe, a comparison with average indicators would be unjustified; a comparison with Germany and Sweden as corporatist economies is more meaningful. These countries have well-developed systems of social insurance and leftist movements. Spain, as a more traditional conservative model of a welfare state, can also serve as a benchmark. The share of respondents in favour of greater equality has risen in Germany after the 2009 recession, from 63% to 75% (WVS data). In Spain, the proportion of those who value equality has also increased, from 40% to 59%. In Sweden, the share has remained stable since the 1990s, ranging from 52-55%. These figures are far above those in Russia.

Fig. 1. Attitudes towards economic equality

Source: World Values Survey

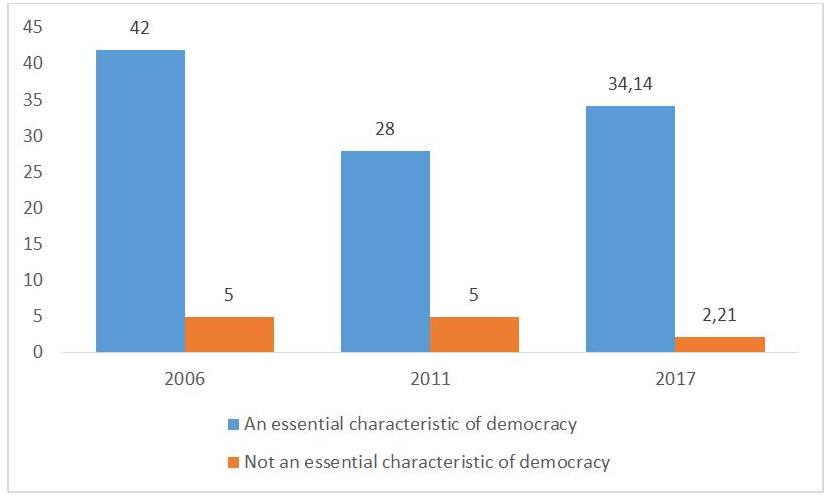

Russia’s transition to democracy failed partly because democracy was associated with prosperity. At the same time, the population had high expectations for non-monetary benefits. The share of those who regarded high taxes and income redistribution as the key feature of democracy dropped from 41% in 2006 (the earliest available data) to 34% in 2017 (see Fig. 2). We do not see long-term trends that would indicate an increase in demand for greater redistribution or state aid.

As research on redistributive policy in Latin America by Alisha Holland shows, if citizens receive little public welfare, they are less likely to prefer greater redistribution. The higher the prosperity of respondents, the less likely they are to be in favour of large-scale redistribution policies. Surveys confirm this tendency in Russia.

In the 1990s, despite social expectations of a welfare state, citizens one way or another learned to survive on their own. Both the state and business are perceived negatively, although business causes more distrust. More than 50% of the respondents in the latest wave of the survey, conducted in autumn 2017, believe that the share of state ownership should increase at the expense of private ownership. This reflects widespread distrust of business, which outstrips distrust of the state. In that vein, 49% of respondents in a 2017 survey believed the state was responsible for citizens’ welfare. As few as 25.6% regarded individuals themselves as responsible for their material well-being. Thus, it turns out that the state is deemed responsible for citizens’ well-being. But there is no enthusiasm when it comes to large-scale redistribution policies involving progressive taxation.

Fig. 2. Attitudes to income redistribution as an essential characteristic of democracy (Democracy: Governments tax the rich and subsidize the poor).

Source: World Values Survey

Of course, political preferences attributed to the left do not boil down to redistribution alone. Solidarity and responsibility towards other members of the community lie at the heart of left wing thought.

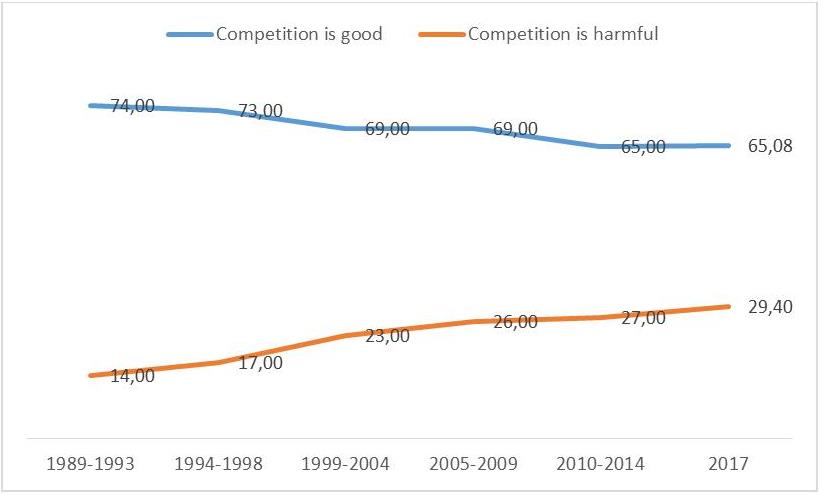

This can be juxtaposed with right-wing ideas that focus on competition and individualism. The philosopher Ayn Rand placed the highest value on individual success and competition. How has Russians’ attitude towards competition as a value changed over the years? According to the World Values Survey, it underwent significant changes: In contrast to the boom of individualism in the 1990s, the Russians were more leery of competition in the 2000s. In 1991, as few as 14% considered competition harmful, while in 2017 this figure was close to 30%. In 2017, the share of those who preferred equality to freedom was about 43%. Almost 50% valued freedom higher than equality. This is quite a lot for a country with a communist past.

So in fact, we’re not observing a massive turn to the left. There is demand for solidarity, maybe. Expectations of a more active role for the state, however, are more about the distrust of the private sector. It may well be as well that such a demand for solidarity has nothing to do with leftist ideology, and might be more reminiscent of European Christian democracy.

Fig. 3. Russians’ attitude to competition

Source: World Values Survey

The turning point and turn to the left could be observed in 2018 as a reaction to the raised retirement age. Such a hike did not go unnoticed, despite the Kremlin’s efforts. Levada Centre analysts studied whether attitudes to pension reform influenced electoral choices in autumn. They concluded that there was probably no such effect, except for a few regions. No universal tendency was identified. On the whole, it was not citizens who grew more leftist, but the state that made a sharp right turn in economic policy.

Navalny’s manifesto now contains items on Vladimir Putin’s May decrees and the role of trade unions. It is the word ‘trade union’ that gives the manifesto its leftist flavour. Yet look in more detail, and many fundamental elements of a social-democratic platform are missing. There is no mention of tax reform, income redistribution or expansion of the state’s social commitments. After all, we are dealing with a classic liberal approach: the fight against monopolies, optimisation of government spending and the fight against corruption (note that Adam Smith also condemned state corruption). Besides, the interests of the working class and trade unions are by no means leftist. Trade unions can share different views including rightist ones (as happens in the US, France and Poland). Finally, the existence of trade unions is typical not only of social-democratic systems but also open liberal economies such as the US and UK.

Speaking of Navalny’s political support base, we must admit to knowing surprisingly little. None of the surveys capture Navalny’s supporters as a separate socio-demographic group. The most recent online survey focusing on identifying Navalny’s proponents actually failed to define a portrait of a typical supporter. All that we know today is that it is a diverse group of people united not so much by a ‘negative consensus’ (anyone but Putin) as by a conscious choice to support the opposition. Yet, let me reiterate that this is one of the key gaps in the study of public opinion: we know very little about today’s opposition.

Are the Russians becoming more leftist? There is no ready-made answer. My hunch is to doubt it. Is Navalny drifting towards leftist ideology? Again, there is no ready-made answer. As a public politician, Navalny has to follow the tides, like a surfer. Since the pension reform raised general discontent among potential voters, it was only logical to support them. Navalny’s intermittent cooperation with the Communists should be seen as a tactical manoeuvre. It is akin to his ‘smart voting’ project, when he called for support of the parties which were most likely to cause inconvenience to the United Russia party. From the point of view of a party which was itself excluded from the elections, this strategy would have been most detrimental to the main opponent. Thus, Navalny supported a candidate from the Liberal Democratic Party in Khabarovsk. So these initiatives should not be assessed ideologically; they are aimed at tactical coalitions. This is so rare in Russian public politics that people are unaccustomed to it.