As the gasoline crisis intensifies and tax hikes materialize, a new problem with no practical answer has emerged since summer. How can officials keep companies investing, the primary driver of whatever ‘gains’ Russians have enjoyed since the invasion? Rather than puzzle over a Trump-Putin summit in Budapest or the latest drone and missile attack escalations against Ukraine, observers would be well-served to dig deeper into how the fight over investment will play out. Investment since 2022 has been comparatively inefficient at bolstering growth because of how much has been centered in military enterprises or low-productivity sectors in services, things like tourism and hospitality. But without it, the war becomes an economic wrecking ball. The Bank of Russia is apparently satisfied that investment and business activity continue to grow despite market contractions noted in the S&P Purchasing Managers’ Index and various indicators of worsened business conditions.

While interest rates may fall in the coming months, the pace at which they decline will be slow, if at all, and immaterial to the broader challenge facing a growing range of sectors. Oil prices have fallen to near five-year lows, Brent crude is now scraping $ 60 a barrel, and the Urals blend has slipped below the EU price cap at $ 48. Grain exports are down. Coal exports have stabilized, but China’s demand is down this year, likely forcing more haircuts on price. While it’s just one market analysis to consider, the Bank of America is already warning of potential downside risks that oil falls below $ 50 a barrel, a price that would be ruinous for Russia’s finances.

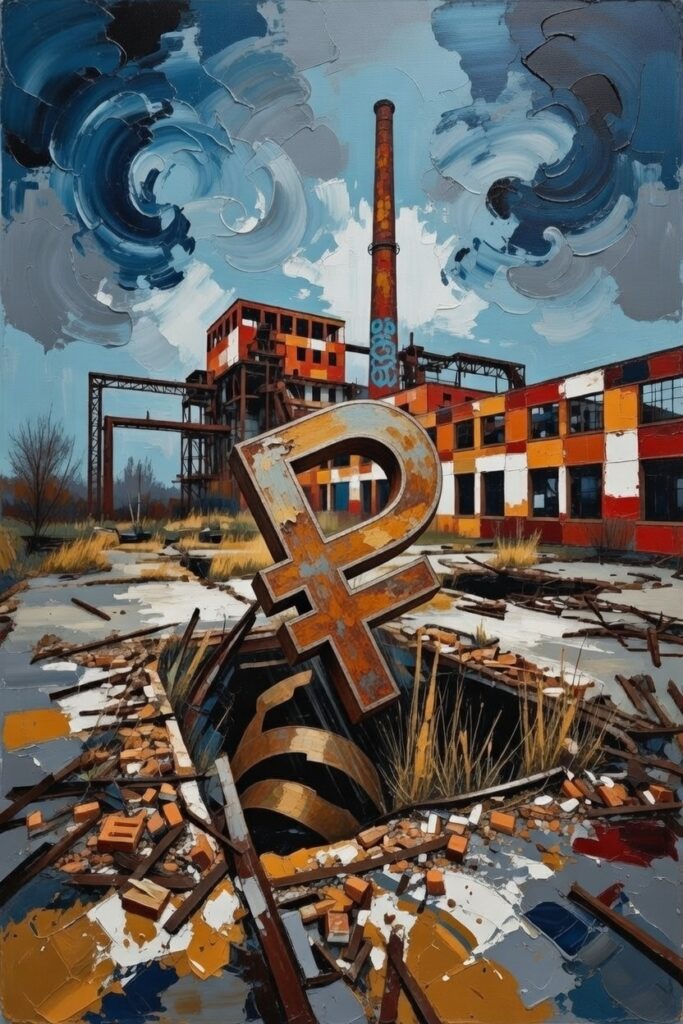

Export earnings aren’t just the lifeline for foreign currency. They underwrite the profits that are redistributed through a wide range of procurements, orders, and local investments across the country. There is no world in which hiking taxes on consumption, small businesses, or incomes can close this widening gap. The only way to drive up revenues on a sustainable, sound basis is to increase investment to prop up GDP growth. To achieve this sustainable growth, you would also need to see real wage increases beyond the overstuffed, padded distortions that Rosstat now publishes, frequently divorced from actual cost of living.

Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin fired a warning shot, if a subtle one, that deserves more scrutiny in the fight to prop up investment. Under the cover of the National Project «Infrastructure for Life,» Mishustin is proposing to compensate industrial enterprises for costs incurred from the construction of housing for their employees. This is, at once, the Platonic ideal of Russia’s austerity logic and a sign of immense systemic stress disguised as a cost-of-living intervention. Marat Khusnullin is assuring people there aren’t risks of developer bankruptcies and touting the 100 million sq. meters of new housing to be built this year — a pace lagging both targets and 2021 — but his confidence papers over the immense burden of mortgage costs for borrowers.

If the cabinet is simultaneously trying to raise tax revenue and planning to compensate large companies for building housing that will ostensibly go towards a policy target, they’re openly admitting market conditions aren’t expected to improve enough to sustain a larger building expansion where demand is strongest. This is a game of hot potato, with different ministries plotting their own forms of policy support or interventions to convince businesses to keep investing amidst extreme uncertainty at cross-purposes to the Bank of Russia’s monetary policy and other policy targets.

The situation becomes even more Byzantine and pointless when Putin openly intervenes to chide utilities providers not to «mechanically» cover their expenditure needs with an increase in costs for consumers. Without adequate earnings relative to costs, the only option for these companies to sustain investment is debt at high rates or subsidized rates that spur more inflation. These pressures come as the underinvestment and shoddy maintenance of existing utilities infrastructure are compounding future repair and construction costs. National oil pipeline monopolist Transneft is already axing investment projects to cover expenses, an increasingly regular occurrence wherever existing infrastructure can be run into the ground.

The orthodox thinking goes that high interest rates are making it more attractive for companies to hold their money in deposits than to invest. Undoubtedly, this is true in many cases. But it avoids the self-evident problem that no one has any clue what their markets will look like in 3−12 months’ time and, in the case of state companies, that dividend payments feed into budget planning. As the deficit grows, those dividends become more important to protect. In the case of the energy sector, MinEnergo now sees no need for legislative effort to force companies to direct more capital to investment over dividend plans despite having signaled support in principle back in July. What seems more likely to happen are situations similar to the coal market. State interventions or bailouts will leave companies on the hook to do as they’re told to an even greater degree than usual.

With these considerations in play, the final arrival of a large oil market surplus coupled with spiraling logistics costs from gasoline shortages and tight diesel markets are a perfect storm. The pace of gasoline price increases is outrunning topline inflation at 11% since the start of the year, but much higher in regions with the most extreme shortfalls. The National Automobile Union is now calling for a price ceiling, a large step beyond the current fuss over the «damping» mechanism as higher domestic prices allow refiners still operating to net healthy profits. Of course, an intervention at that scale would reinforce the emergent rationing regime spreading across many regions. But these prices are going to drive inflation higher, holding interest rates higher for longer and reinforcing the cycle of saving or paying out shareholders over investors.

Desperate times call for creativity. Pension funds will be allowed to invest in startups, a way to offset a weak venture capital market that has become less transparent since 2022. But this is chump change compared to state enterprises or large firms. Consumers can’t provide the demand certainty needed to calm businesses’ fears. They can’t even predict how long they’ll have to queue for fuel or what will survive MinFin’s budgetary chopping block as the pressure to cut intensifies over the fall. For now, the investment question is a hot potato. By January, it may well be a hand grenade.