Every year, on the eve of elections, Russia’s electoral legislation undergoes changes. This is a concerning signal in itself, as international standards demand stability in such laws. Constant adjustments to election rules clearly indicate manipulation of legislation for short-term political gain by forces controlling the legislative body. To prevent such practices, some countries have a rule that changes only take effect after one parliamentary term, ensuring even the next convocation cannot benefit from them. In Russia, it’s different: significant amendments to electoral laws are adopted annually, typically taking effect in May, just days before the start of the unified voting day campaign. This year is no exception.

Cancellation of By-Elections to the State Duma and Redrawing of District Boundaries

In late May to early June 2025, by-elections for the State Duma were scheduled, as seven electoral districts in seven regions lost their representatives in the federal parliament over the past year. Only one case was due to a deputy’s death; the others resulted from voluntary mandate relinquishments for career advancement: two became regional governors, two took deputy minister positions in the federal government, and two became vice-governors in the Republic of Altai. As a result, over 3 million voters were left without representation in parliament.

However, by-elections in 2025 will not take place: in May, the State Duma passed an amendment canceling them for this year. With the main elections scheduled for 2026, no by-elections will occur in 2025. In practice, this means over 3 million voters will remain unrepresented in parliament for over a year. For example, in the Biysk district of Altai Krai, where deputy Alexander Prokopyev relinquished his mandate on July 3, 2024, voters will lack representation for 15 months, or 25% of the current Duma convocation’s term. In this context, the cancellation of by-elections appears questionable from the perspective of voters’ rights.

Simultaneously, another amendment was adopted, worsening the electoral situation. Now, single-mandate district boundaries will be redrawn every five years instead of every ten, opening opportunities for gerrymandering—manipulating district boundaries—before each election. We saw this in 2015, when the current boundaries were set, and again in 2025, when boundaries were redefined for the upcoming 2026 elections. In 2015, «petal-shaped» districting was used: large cities were split into parts, combined with vast rural areas, minimizing the influence of protest-prone urban voters. In 2025, the redistricting was less radical but still telling. Over the years, Russia’s Constitution was amended to include four new regions (occupied Ukrainian territories: DNR, LNR, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson regions), which were to gain representation in the lower house of parliament. These four territories received seven single-mandate districts. Additionally, voter numbers grew significantly in Moscow, the Moscow Region, and Krasnodar Krai, each gaining one additional district.

In the 2021 elections, these regions showed excellent results from the Kremlin’s perspective: in Moscow, seven of 11 districts were won by United Russia, three by «Sobyanin’s list» independents, and one by Just Russia’s Galina Khovanskaya; in the Moscow Region, all 11 districts went to United Russia, and in Krasnodar Krai, all eight. Krasnodar Krai and the Moscow Region are known for widespread falsifications, while Moscow extensively uses opaque electronic and online voting.

To create new districts, ten single-mandate districts were taken from other regions, affecting areas with opposition leanings. In the current parliament, only 22 of 225 districts—less than 10%—went to «opposition» parties (meaning non-United Russia). Five of these (nearly a quarter) are in the regions now losing districts, a disproportionately high share.

The situation in Altai Krai is particularly telling, where one of four districts is being eliminated—the one won by strong Communist candidate Maria Prusakova. Her district is being split among the other three, despite the region already having an unrepresented district (Prokopyev’s) for nearly a year, and despite higher population losses in other districts.

In Smolensk, Tambov, Tomsk regions, and Zabaykalsky Krai, the situation is simpler: instead of two districts, each will have one, making re-election harder for non-United Russia deputies. In Zabaykalsky Krai, Just Russia’s independent deputy Yury Grigoryev will face new voters, while in Tomsk, LDPR’s Alexey Didenko faces similar challenges (compounded by issues with his party’s new leadership).

The case of Tambov’s eliminated district is more complex. One district is held by Rodina’s Alexey Zhuravlev (formally in the LDPR faction but chair of Rodina). In 2020, Rodina won a majority in Tambov’s city duma, with Maxim Kosenkov, a local Rodina leader, becoming mayor. Kosenkov, a former mayor and vice-governor in the 2000s, was expelled from United Russia, making him relatively opposition-oriented in 2021. By 2025, however, he returned to the ruling party.

Smolensk was previously managed by LDPR (with governor Alexey Ostrovsky, a Zhirinovsky appointee). After Zhirinovsky’s death, Ostrovsky resigned, and the LDPR’s district is likely to be lost.

As a result, the 2026 elections are expected to further reduce the number of opposition single-mandate deputies in the Duma.

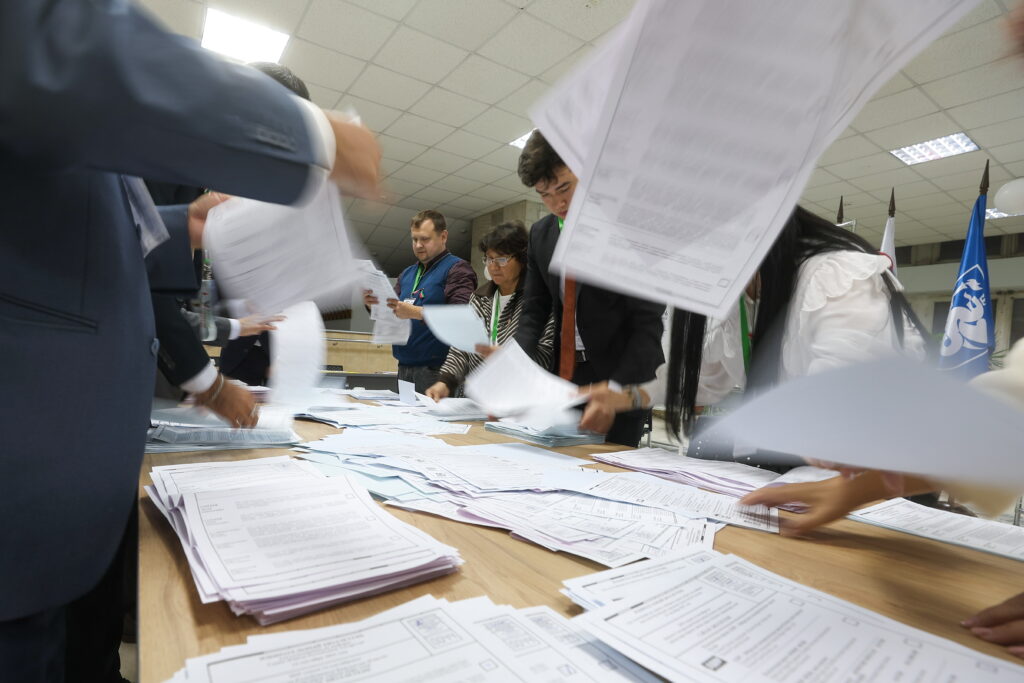

The Fight for Paper Ballots

The most debated spring amendment, proposed by the Central Election Commission, effectively made paper ballots optional if a region opted for electronic voting. This faced strong opposition from both the public and political parties, prompting Duma Speaker Vyacheslav Volodin to delay the bill and send it for revision.

The amendment was revised to guarantee voters a paper ballot even in regions with full electronic voting, as recently seen in Moscow. Previously, the law didn’t address this, as older electronic voting systems included a paper trail to verify votes. New terminals used in Moscow lack this, offering no way to cross-check results. Ideally, election organizers would be required to ensure electronic systems allow manual recounts, but this wasn’t done, making the amendment largely cosmetic.

Moreover, it’s now officially permitted to aggregate electronic voting results into a single database without breaking them down by polling station, preventing analysts from using statistical methods to detect anomalies. Russia’s electoral system has taken another step toward Belarus’s model, where polling station data is entirely absent.

Money, Criminal Records, and Party Oversight

The adopted bill includes several other amendments.

First, donation limits for political parties were significantly increased. Previously, a party could receive up to 4.33 billion rubles annually. Now, the limit applies to «total permissible annual donations to all regional branches,» with each branch allowed 86.6 million rubles, raising the total to over 7.7 billion rubles—nearly double.

Inflation and rising party costs justify this, but with state funding heavily favoring United Russia, the previous 4 billion ruble limit made it impossible for others to compete. However, it’s unclear how this will play out, as fewer people are willing to participate in politics as candidates or donors, potentially widening the funding gap despite the intent of ensuring party equality.

Second, election commissions are no longer required to publish candidates’ criminal records, likely paving the way for «SVO veterans» to appear on ballots, though their influx remains limited.

Finally, election commissions and the Ministry of Justice can now film party events, likely creating hurdles for parliamentary parties by providing grounds to disqualify undesirable candidates or parties.

Overall, electoral legislation continues to deteriorate, seemingly beyond repair. The relentless tightening stems from ongoing fears among domestic policy overseers of an unexpected crisis due to lack of genuine voter support. The 2011−2012 protests remain a lingering trauma for the current domestic policy bloc, despite many opposition experts and activists believing the Kremlin’s position is unshakeable.