The contours of the coming economic crisis have only just started showing in Russia’s regions. Outside of cities where the service economy is feeling the heat already, and some industrial centers where a ban on technology imports caused disruptions, sanctions have not been very painful for most of Russia yet. But this is not a sign of a healthy economy; rather, as Central Bank chief Elvira Nabiullina warned in April, this means the worst is yet to come. As industries that rely on foreign ingredients and components run out of pre-invasion reserves, the situation will worsen.

Apart from actual sanctions, «self-sanctioning» companies and buyers play a key role: shipping companies that are shunning Russian ports make the import even of unsanctioned goods slow and tricky. Russian oil is selling at significant discount, if at all. Oil production has already dropped by 9 percent, and the withdrawal of oilfield servicing companies will exacerbate the problems further. The list could go on. These withdrawals are likely here to stay for the foreseeable future: both the EU and the US are looking to lock them in by various means, e.g. prohibiting investments that will prevent Western companies rushing back ahead of time, and likely sanctioning marine insurance, which would make it very difficult for Russia to pivot its oil exports to Asia.

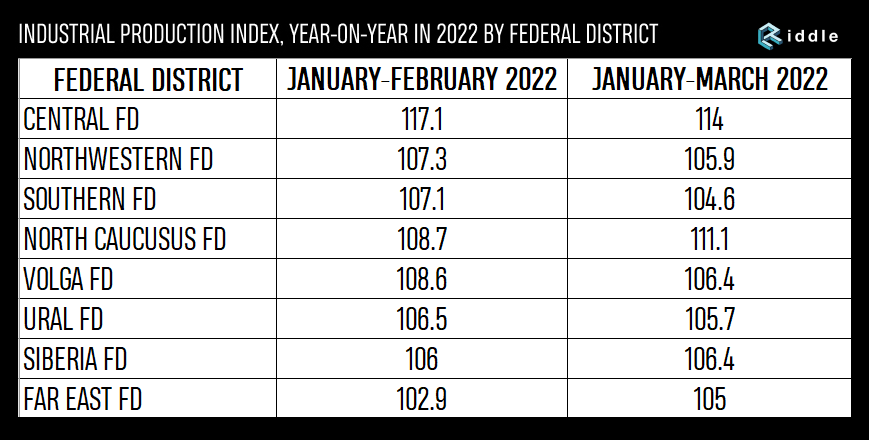

Not all Russian industries and regions suffer to the same extent and at the same time. Rosstat’s figures about industrial activity in the first three months of 2022 allow a glimpse into what sectors and regions are already affected. First off, there are two diverging trajectories. Growth in the Far East, Siberia and the North Caucasus was still accelerating in March. The rest of the country, however, is slowing down. Among the regions, which experienced the most significant drop in industrial production we find regions housing industries such as car manufacturing (the Samara and Kaluga Regions), petrochemical plants (Nizhny Novgorod Region) and machine building (Mari El). Several Western border regions and the regions containing Russia’s biggest cities have also already suffered. Next in line could be oil producing regions, such as the Republic of Komi, Tatarstan or the Tyumen Region, and regions relying on «semi-sanctioned» industries such as metallurgy, which depend on foreign equipment or are facing problems maintaining trade relations.

The early downturns have already prompted local and regional leaders to redraw fiscal plans in industrial cities and regions such as Nizhny Tagil, home to the Uralvagonzavod machine-building factory, or Kaliningrad, which experiences growing isolation and an exodus of Western investors from its automotive industry. Over time, however, most regions will be affected if, as now looks likely, oil production will drop further, as, following two decades of fiscal centralization and an uneven investment growth, Russia’s federal budget essentially redistributes oil and gas rent — around 45 percent of all federal revenues — among regions that need to cover essential social expenses.

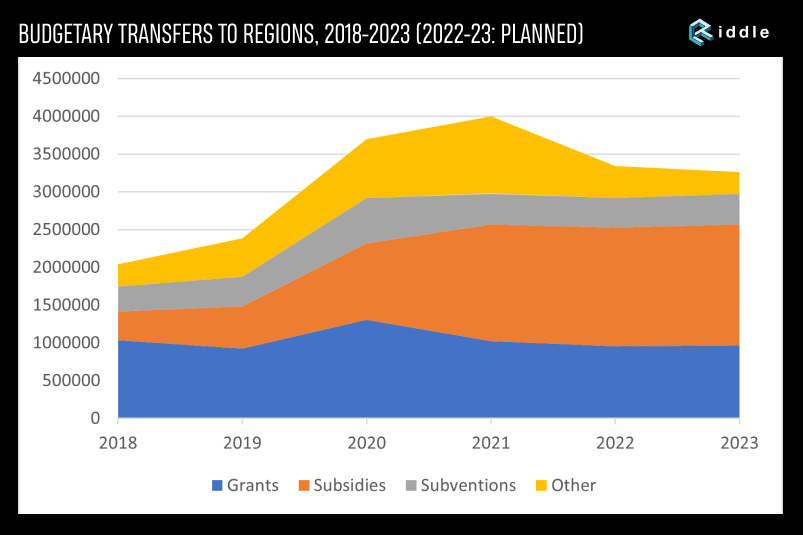

Regional budgets, as a whole, are not in a particularly bad shape, given the circumstances. As of 2022, 23 of 83 Russian regions were classified as «donors» — not receiving federal grants to ensure the viability of their budgets. This is ten more than in 2021, although this is partly the consequence of the relative reduction of grants within budgetary transfers in favor of transfers that come with strings attached (subsidies, subventions and «other transfers»). Budget receipts grew substantially in 2021 (26% on 2020) and in the first quarter of 2022, leaving regions, across the board, with 3.5 trillion rubles of balances as of March. However, given the uncertainties about the coming economic shock, and regions’ reliance on two main sources of income, corporate and personal income taxes, both of which will likely be severely hit at some point, this might not be enough. Most regions did not have enough reserves to support local economies during the pandemic-induced economic contraction of 2020, even after a relatively prosperous 2019. Moscow, a uniquely rich region, could afford to finance a subsidized credit program. It should give a sense of the gravity of the coming crisis, then, that this time even the wealthy capital has so far approached the crisis very cautiously as it rethinks its ambitious urban development agenda and faces a looming crisis in its commercial property market.

To address regions’ responsibilities and their fiscal space in the current crisis, Putin issued two decrees, one in March, outlining their responsibilities, and another one in April, containing a list of policies aimed to help regional budgets. On May 1, he signed a law on additional transfers to regional budgets.

The list of obligations is long and quite exhaustive. As always, the president expects governors to keep their regions quiet and loyal. However, the crisis is expanding the meaning of this. According to Putin’s decree and his accompanying address to the government, regions should first and foremost ensure that prices do not go up too much and that essential goods are available. They should do this without manual price controls: by compelling exporters to sell products domestically at conveniently low prices and by increasing their budgetary reserves. They should do this all while implementing all planned investment project, in order to create domestic demands for industrial goods that Russia can still produce, but has trouble selling abroad, such as metals and other construction materials. They should be able to do this while fighting a COVID crisis, which did not go away, and — in the case of a fair number of regions — mitigating the consequences of natural disasters. A wish list that puts the word «priorities» into perspective.

A significant proportion of the money that will be pumped into the Russian economy will not go through regional budgets: the federal government is going to try to pump more money into companies through VEB’s «project finance factory», a state-backed credit instrument. Large state-owned enterprises — Aeroflot, Russian Railways and DOM. RF, a mortgage lending vehicle, will be recapitalized from the National Welfare Fund, to keep afloat major capital investment projects, such as the North Sea Route or the expansion of main railway lines.

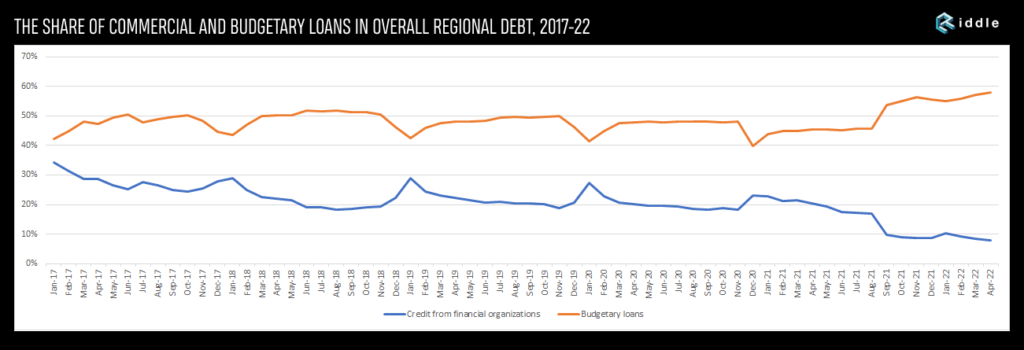

With the focus being elsewhere, the fiscal instruments that the government is putting at the disposition of regions have been fairly modest, unlike their responsibilities. Some amount to a small recalibration of existing policies. Budgetary grants will be indexed, but their overall proportion within transfers will not change considerably. Infrastructure loans, a 500-billion-ruble instrument created by the government last year to stimulate grand investment projects in the regions, can be repurposed, and the government will provide more of them in 2022; but the loans remain subject to the government’s oversight. The government will increase the amount of cheap budgetary loans that regions can access to replace more expensive market loans: they will have access to 390.7 billion rubles to pay back obligations maturing this year, and can take out further loans at 0.1 percent rates maturing in 2029 to increase their fiscal space. This extends a policy that the government has followed since 2016.

Similarly to the COVID crisis, however, policies will remain under the effective control of the federal government, as will financial resources. If anything, regions are likely going to be even more dependent on federal transfers than in 2020−21, given that governors do not even have the room provided by loosening or tightening pandemic-related restrictions to stimulate economic activity. The only novel budgetary instrument, «single subsidies», which would allow regions to tweak policies at will in order to achieve pre-set policy objectives, will only be rolled out in the richest regions as a pilot project, and even there, it is unclear what level of freedom regional governments will actually have to rearrange priorities.

The government’s fiscal policies and the coming crisis, which will likely require the state to assume an even bigger role in Russia’s economy, also align with the direction of last year’s public administration reforms. These strengthened the political authority of the president and the federal government over regional governments, as well as the political and fiscal authority of governors over municipalities. The first gubernatorial appointments of this year — mostly officials from the president’s cadre reserve — underline this. In the circumstances of significant economic disruptions, falling revenues and missing private investment, the role of officials who can ensure that money keeps flowing to key sectors and industries will grow. Governors were already explicitly prompted by the Finance Ministry to assume more control over the finances of municipalities.

The longer scarcity continues and the deeper the economic disruption is, however, the more important will another issue become: which regions will have priority access to the federal arbiters of these funds as they become increasingly scarce. The federal budget has ample reserves now, after a surplus of 1.15 trillion rubles in the first quarter of 2022 and with a still continuing inflow of oil and gas windfall income, which can, since March, be immediately put towards mitigating the cost of sanctions. But as the time horizons of the war shift, it is unclear how long these funds will keep coming. The Finance Ministry recently lowered its estimates of extra oil and gas revenues for May. It is likely that the government has been keeping purse strings tight and policy details vague because of this heightened uncertainty about future fiscal receipts.

Needs and opportunities will not always align. The occupied Crimea and the Far East will likely remain priorities due to fears of separatism. Regions with special access to the president may have an easier time getting transfers, like Chechnya, which has received assurances that the federal subsidies underpinning its economy will not be cut, or the Kemerovo Region, whose governor, Sergey Tsivilyov, is related to Putin by his marriage, and has already lobbied the president to help the region’s struggling coal industry by freeing up railway lines. Needy regions meanwhile may have to wait, irrespective of whether they already face higher-than-average inflation (and in some cases, military casualties). Also stuck at the back of the queue for subsidies will be regions with functional industries, which face the steepest decline as their economies are disrupted.

The horror of the 1998 financial meltdown to many federal officials was how it prompted regions to adopt their own fiscal and financial policies, even if that meant openly defying Moscow. The Russian political and administrative system is very different now. As Russia faces its biggest economic crisis since 1994, this will also be a test of its current political system: a peculiar mixture of technocratic digital authoritarianism and a short-sighted, corrupt personalist autocracy.