In June 2019, the Russian academic sphere saw a series of scandals: political scientists Aleksandr Kynev and Elena Sirotkina from the Moscow Higher School of Economics and Valery Solovey from MGIMO were conspicuously fired, and the St. Petersburg State University’s decision to reduce the number of faculty in its History Institute triggered a wave of student protests.

Of course, dismissals in some way or another linked to politics are far from a new phenomenon in Russia. Political pressure on universities has been happening for a considerable amount of time, from attacks on specific professors in regional higher education institutes to suspensions of accreditations and licenses of entire academic institutions – most notably, “Shaninka” and the European University of St. Petersburg, the latter of which recently had its accreditation restored. But this is perhaps the first time that a substantive public discourse has emerged on the prospects for social sciences and humanities research in authoritarian regimes. This is in no small part due to the fact that these scandals revolved around political science institutions specifically, and that the figures involved were people and universities with considerable public resources.

This text is not meant to be a continued investigation into these recent events, but rather an attempt to examine the ability for political science research produced in unfree political systems to exist on the international academic market. I find that in fact, political science can exist just as well in autocracies, but it comes at the price of reduced competitivity. Imagine, if you will, a race where one of the participants has to run in a sack or a spacesuit – an inconvenience, to say the least.

Academic freedom in Russia

Academic freedom is an aspect of civil and political freedoms which, as is known to any student of political science, is not guaranteed in authoritarian regimes.

However, even among stable and relatively economically developed autocracies, the degree of repression in the academic sphere varies. In some cases, repressions are predominantly structural in character, taking the form of bans on foreign funding and other regulations on academia and education (standardization of textbooks and teaching, etc.). In other cases, academic freedom is still formally guaranteed, but targeted persecution of academics is more common. So while in Russia foreign sources of funding are effectively prohibited, in Kazakhstan, on the other hand, the activities of international foundations are in general not restricted.

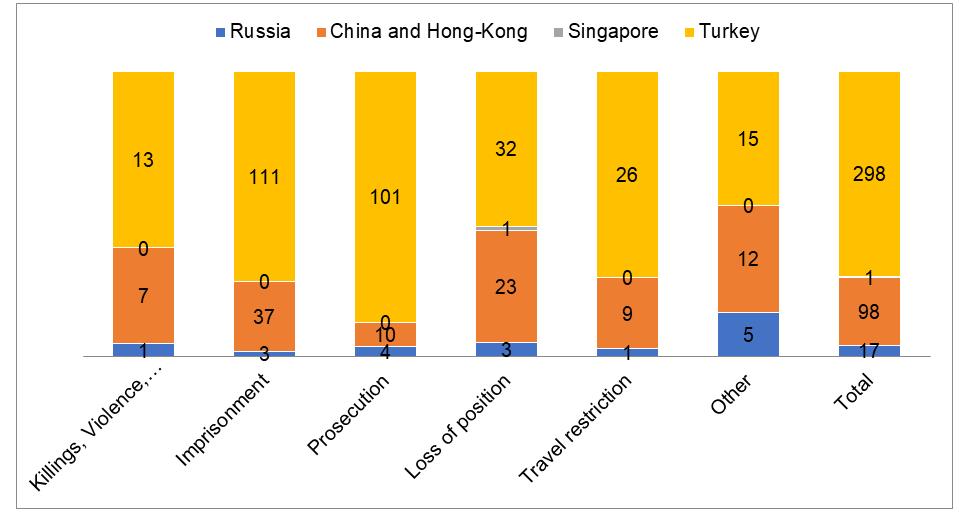

The international project Scholars at Risk (SAR) makes records of targeted attacks on academic freedom, from dismissals and threats to imprisonment and killings. Even when accounting for possible imbalances in the data on the academic population per capita and other data errors, Russia does not come out looking like a ‘winner’ here. Among the regimes studied, one of the most repressive in the academic sphere is apparently Turkey, while Singapore, despite the fact it is not an electoral democracy, practically doesn’t persecute academics (excluding one case where a contract in a journalism faculty was not renewed). Another country that comes off worse than Russia is China – here, we should also keep in mind the closedness of the Chinese regime and that therefore, compared with Turkey, where data is likely accurate, the data on China is seriously underreported. Unfortunately, SAR does not offer data on Kazakhstan, which would likely be the closest reference case for Russia. In sum, autocracies repress in a variety of ways, and Russia, oddly enough, is closer to the case of Singapore than to China.

Graph 1. Proportion of repression in academia, Russia in comparison with China, Turkey, and Singapore

Source: SAR

Is a career in political science worth it if you live in Russia?

To be brief, no – remember the metaphor about running in a sack. But what should you do if you are already working in the field? Is there any point in conducting political research into, for example, regime change, electoral politics or protest movements when such topics are censored in mass media, particularly when funding comes exclusively from the government? At first glance, this seems like a risky undertaking or, at the very least, best left to people who do not plan on being promoted to administrative positions in their universities.

Recently, discussions on social media highlighted a few positions on this issue that might be summed up as follows:

- “Sane” political science cannot exist in non-democratic countries, since it requires civil and political freedoms, and if it does exist, it only serves as a training platform for propagandists;

- Political science can exist, but only in a form limited to “safe” research financed by the government, while anything else is at your own risk;

- Political science can exist, but one has to simply, as Konstanin Sonin puts it, “break through the asphalt”.

The first assertion seems to be the most coherent one theoretically, although in practice the other two are backed by empirical evidence. The examples of the European University of St. Petersburg and Moscow HSE clearly demonstrate that it is possible to be published in prominent foreign journals without needing to edit down to every last word. Despite the authoritarian consolidation seen in the country, political scientists have made important breakthroughs, considerably strengthening their methodological framework and leaving the ghetto of descriptive studies. What is more, the top political science departments in Russia have supplied talented graduate students to leading universities around the world.

Let us try to understand the mechanisms of academic censorship using the tools of political science itself, considering the risks and resources of a political science career. Political scientists need resources in the form of research grants and links with the academic community. At the same time, major financial projects and controversial research topics are associated with risks, as we will see below.

Risks

It might be helpful to start off by bringing up a curious phenomenon discovered by political scientists, which tells us why and when members of district electoral commissions will work more or less diligently to help falsify election results. Ashley Randlett and Milan Svolik’s study on the 2011-2012 Russian elections shows that when an incumbent does not particularly need vote tampering, agents (electoral commissions) will cover their bases and “top up” the votes in the incumbent’s favor regardless. And, on the contrary, when there is real electoral competition, these agents will not commit crimes or deliberately tamper with the procedure or results of the elections out of a desire to avoid unnecessary risks. In other words, when incumbents need help the most, they are likely not to receive it because agents tend to be risk-averse. But when everything is going well for incumbents, they might receive “gifts” amounting to up to 140% of the vote.

How does this phenomenon link to the issue of academic freedom and the persecution of political scientists? Basically, state universities, or their administrations to be more precise, are essentially the same types of agents, trying to avoid risks and even anticipate them. This is primarily dictated by the nature of the institution’s financing and the inability to receive significant funding from alternative sources. Ultimately, as concerns the top universities, their mission is, as a rule, to lead modernization efforts in science and education. Thus, flagship institutions such as Moscow HSE are on the one hand becoming enclaves of government deregulation, and on the other hand, agents entering into contracts with their principal, the state, that tend to put the agent in a vulnerable position. This is because essentially, financing so-called “pockets of efficiency” or growth points in authoritarian regimes is like a sort of quicksand made of personal guarantees. Therefore, the agent in question does not have many opportunities to protect itself if the principal-state becomes dissatisfied, which is why the agent has a strong interest to calculate the consequences of its actions and formalize all records itself. In theory such an incentive emerges in any contractual relationship, but in hierarchical conditions where the rule of law and the effectiveness of institutions are problematic, there is an even higher incentive to protect oneself. This is likely where the love in many modernizing autocracies such as China, Singapore, or Russia for compiled ratings and other benchmarks comes from.

Having academics research “uncomfortable” topics is not problematic on its own. Authoritarian regimes allow themselves to be studied and do not particularly fear science, let alone specific academics and researchers. It is no secret that the wider public rarely reads academic articles, especially if they are published in English. Moreover, within academia getting citations is no trivial task. A researcher only becomes a problem when university bureaucrats begin to see them as an unnecessary risk.

Considering this, how do agents organize their work, and what are their mechanisms of risk insurance? The first mechanism consists in the bureaucratic precautions taken by administrators or internal “enforcers” – “just to be on the safe side”. Bureaucratic risk insurance (which includes, for example, compliance of academic programs with national standards, of employees with professional qualifications, and of publications with numerous ratings and statistics, etc.) encourages a constant overestimation of potential risks on the part of bureaucrats. The gradual increase in the number of such enforcers leads to the formation of an independent force within the organization which begins to dictate on its own terms and influence anything from organizational and personnel decision-making to even the content of academic programs. Strictly speaking, this is not a political mechanism, but it often leads to self-censorship. For example, a thesis topic might be rejected or a grant application name changed “just to be on the safe side”. This is without even considering the need to compile cumbersome application paperwork and other supporting documentation which is usually not useful to anyone. The regime makes it necessary to acquire specific risk reduction skills for the survival of one’s own career that are not useful in any other situation.

The second mechanism, unfair competition, is explained by in-fighting in academic circles to get prestigious administrative positions; in a politicized and high-risk environment, this can take on perverse forms. When receiving external signals about a threat, an agent, as a rule, has a choice in how actively they react to it; whether or not this reaction leads to repressive actions is often determined not so much by external pressure as much as by internal interests and career-related in-fighting. Both mechanisms are ways to insure oneself against risks, but they operate differently. In this case, one mechanism may reinforce the other, for example, in case of dismissal of a non-cooperative employee under a formal pretext.

Research Topics and Funding

An academic’s choice of research priorities is influenced by the accessibility of funding. This is a direct consequence of the type of regime. The ability to choose one’s funding can only exist in environments where academic freedom is guaranteed. In an authoritarian system, research funding is a politized issue, so as a rule, external financing is limited (with the exception of Kazakhstan). If you work in this type of state, you will not have the same opportunities to react to changes in popular research trends on the international academic market. You are then forced to “trade” only in topics that are tolerated by the state. Often falling into this category in the Russian case is research into youth studies, international security, harmonization of interethnic relations, etc. Of course, there is substantive research being done in these areas, but more often than not they become the victims of what Vladimir Gel’man once called “science without research”.

Modernizing autocracies are sometimes actually quite interested in certain forms of knowledge, for example, research methodologies (generally programming and statistical methods), research into state and municipal administration, ‘digital’ governments, and so on. These are flagship research topics for regimes that have embarked on the path of authoritarian modernization and have decided to create their own pockets of efficiency without needing to dismantle or repair the main structure of the system. The state can generously finance topics it considers useful to increase efficiency in keeping with the “high modernism” spoken of by James Scott. However, systematic research on this phenomenon, alas, has not yet been done.

What, then, are the strategies of “survival” for a political scientist in this system? If one is to look at risk probability and financing opportunities, then the picture looks a little like an old TV show from Kanal 1, “Clever Boys and Clever Girls”, a quiz show where teenagers stand on either a red, yellow, or green track depending on how difficult they want the trivia questions to be.

- On the green track, the academic can consistently snag projects in their research priorities but is forced to compete with “science without research”. The amount of funding is small, and so are the risks.

- The yellow track involves playing the game of authoritarian modernization: here, the academic chooses topics that appear useful to the state. The financing is much higher, and as a rule, is bound by personal obligations or agreements between the parties. The stakes are higher, the risks are higher, but this is the optimal option in terms of academic prestige and research opportunities.

- The red track means the academic can freely choose topics and even funding sources, with a bit of resourcefulness. But at the same time this freedom in research is accompanied by great risks. Strictly speaking, the academic can work in peace as long as they do not become a problem in the eyes of the bureaucrats who are called upon to minimize these risks.

Conclusion

Political science can exist in authoritarian regimes, but at much greater costs. Political scientists are required to invest in specific skills in order to “sell” normal research, which includes writing applications in the language of the “state”, filling out tons of meaningless paperwork, and so on.

One other paradox of modernization projects in education that has emerged is the fact that Russian academia has educated and sent hundreds of talented graduates to study abroad. If Russia followed the example of the “Bolashak” program in Kazakhstan, these students would be obligated to return and “repay their debts”. However, the latest scandals at HSE have sent a clear signal to graduates that it is probably not worth returning, and that in an authoritarian system, bureaucratic skills are always preferred to academic ones.