In early 2020, the Belarusian leadership embarked on a presidential election campaign. A protracted standoff with Russia had left resources thin on the ground. Even so, back then the authorities were in control of the domestic political situation. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic crisis have played into Russia’s hands.

Lukashenko’s shrinking support base

The first COVID-19 cases were registered in Belarus in late February 2020. In response, the leadership took a series of controversial decisions. The healthcare system had been aware of a possible outbreak of a new disease in January. After the first confirmed cases, the Ministry of Health sought to reduce morbidity and increase in-patient capacity to treat COVID-19 victims. By contrast, Lukashenko used scornful, devil-may-care rhetoric in his public statements. He downplayed the threat, comparing COVID-19 to the ordinary seasonal flu. Worse, he blamed those who died from it, claiming it was their own fault because of their poor health. His rhetoric soon changed, but the first reactions left their mark on Belarusians and on the outside world.

The pinnacle of a coronavirus-denial policy was a military parade in Minsk on Victory Day, May 9. This demonstrated that the main goal of Lukashenko’s special path was to outdo the Kremlin, which had conceded to the lead of the so-called civilised world and introduced a lockdown to limit the spread of COVID-19. Thus, the Belarusian strongman tried to at least symbolically get even with Moscow, which had been exerting tough economic and political pressure on Minsk since late 2018.

However, any foreign policy victory was illusory and brought no dividends. It is too early to draw definitive conclusions about the real results of the Belarusian policy toward the epidemic. But by now, there is no doubt that Belarus is ahead of many countries in Europe and elsewhere in confirmed cases. Reported mortality statistics are unreliable; the number of deaths (282 as of June 10) is underestimated and might be 10 times higher.

Belarusians have faced business-as-usual rhetoric from their authorities, who did not provide them with protection and support in the fight against the epidemic. Moreover, Lukashenko’s contemptuous and irresponsible statements implied absolute indifference to the fate of ordinary citizens. The urban middle class and politically active citizens reacted against such foul play. Support for Lukashenko has reached record lows of 3-7%, according to online surveys conducted by Belarusian independent Internet media outlets.

The authorities have also enraged Lukashenko’s core electorate — pensioners and rural voters. These citizens have turned out to be most vulnerable to COVID-19 due to either their age or limited access to reliable information or quality healthcare services. Initially, both groups made little of the disease, as advised by Lukashenko. Then, some of them contracted the virus – and some, or their relatives, died of it.

The government’s policy caused perplexity among other core voters. Conflicts emerged in the healthcare sector; no extra pay for professionals treating COVID-19 patients was forthcoming. Then there are disgruntled teachers, left exposed by business-as-usual instructions from top officials. Lukashenko’s rhetoric and decisions even confused public officials and the siloviki. Many COVID-19 cases have been recorded among law enforcement and the armed forces. When appointing a new government on June 4, Lukashenko urged ‘staggering’ public officials to ‘get in line’.

New (pro-Russian) opposition

The authorities’ inappropriate response to the COVID-19 epidemic as well as a wider economic decline have generated an appetite for protest. It is not so much a protest against the elite or the system as it is against Lukashenko personally.

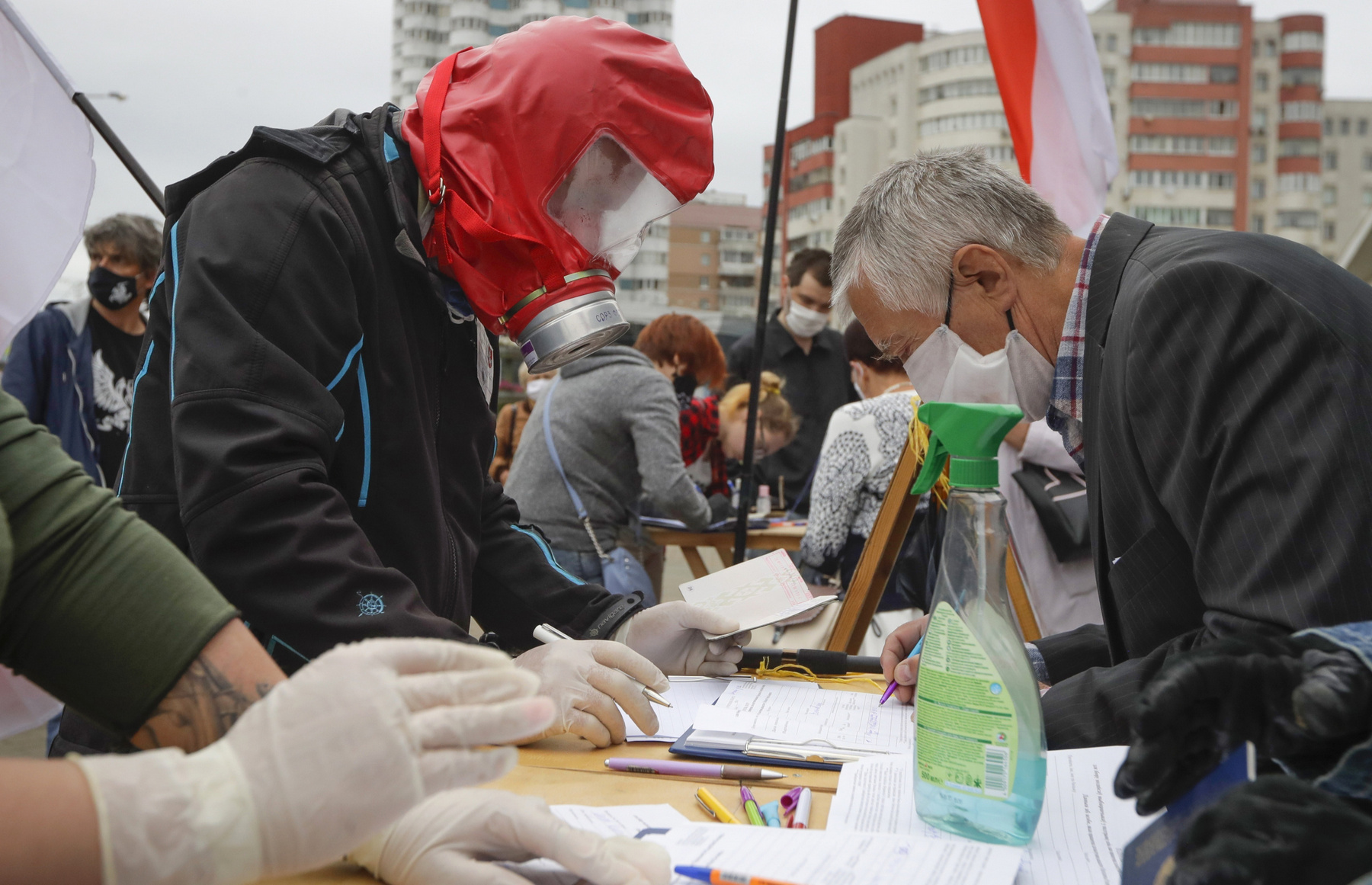

The authorities realise this. The presidential election will now be on August 9 — the height of the vacation season, instead of late summer. But their plan to kill turnout still failed; a record high mobilisation has already occured relating to the nomination of presidential candidates. Fifty-five initiative groups submitted their registration applications. 15 were registered and given the green light to collect signatures.

Three nominees new to Belarusian politics have captured the public’s attention. Ex-chairman of the board of Belgazprombank Viktor Babariko; Sergei Tikhanovski, a blogger and leader of the ‘Country for Life’ protest movement (his wife Svetlana was registered instead of him but he was running her campaign as the head of her initiative group before his detention on May 29); and a former Lukashenko aide, the ex-head of High Technologies Park in Minsk, Valery Tsepkalo.

All three candidates have ties with Russia. Babariko was the head of Gazprombank’s Belarusian affiliate for 20 years. Tikhanovski had quite recently worked in Moscow and made pro-Russian statements early on in his political career. Tsepkalo has ties with Russia as a MGIMO graduate, a serviceman in the Soviet Strategic Missile Forces, an employee of the Soviet Foreign Ministry as well as a former subordinate of Belarusian Foreign Minister Ural Latypov, who is currently residing in Russia.

The new opposition’s obvious ties with Russia have spurred speculation about direct interference by Moscow. The candidates themselves have also provided food for thought. They represent stances compatible with Russian policy (most probably in line with voters’ pro-Russian sentiments). Other than Babariko, they do not flirt with a nationalist-minded electorate. Russian media outlets ranging from Kommersant and Moskovskiy Komsomolets to Telegram are promoting all three candidates.

At the same time, Russian commentators (fervently) insist that the Kremlin has nothing to do with the Belarusian campaign. They note that the Russian leadership allegedly prefers not to interfere. Meanwhile, the Belarusian authorities do not dare tell the electorate that opposition leaders are backed by Moscow even if they know otherwise. Instead, they deploy the ‘Russian oligarchs’ formula. After all, almost two-thirds of Belarusians view Russia positively.

The Kremlin’s stance and strategy

One hit that the Kremlin does not have its own candidate — that is, Russia is not banking on one of the new opposition leaders — is how all three candidates are stepping on each other’s toes. Tsepkalo clearly competes with Babariko for the votes of the middle class, intelligentsia, public officials and business managers. Tikhanovski reflects the protest sentiments of ‘ordinary Belarusians’, migrant workers who have returned from Russia, small entrepreneurs and the shadow sector, thus competing for voters with Lukashenko and Babariko. At the same time, Tikhanovski claims that he will call for a boycott of the election if Lukashenko and head of the Belarusian CEC Lidia Yermoshina do not resign. In other words, there is no single winning strategy.

However, the absence of a Kremlin candidate does not mean there’s no Russian meddling.

To begin with, Moscow is part responsible for the dismal social and economic backdrop of the ongoing campaign. The steady reduction of the oil-and-gas rent and restrictions in mutual trade have had a detrimental effect on the Belarusian economy. The financial standing of many Belarusians has deterioted badly. GDP shrank by 0.3% in the first quarter of 2020 (even before the COVID-19 restrictions.) This was due to a sharp drop in exports to Russia and exports of petroleum products to EU countries after Russia terminated oil supplies to Belarus. During the pandemic, Russia closed its border with Belarus to travellers, damaging the incomes of Belarusians working in Russia.

Secondly, Russia, or rather certain Russian actors, might be involved in the nomination of the three opposition candidates. It is hard to believe any of them could stand for election without at least symbolic support or minimal guarantees of personal safety, which could only be provided by Moscow.

Thirdly, the Belarusian information space is dominated by Russian traditional and social media, as well as tailored outlets established as part of Russia’s enhanced information presence. Russia exerts its influence not to support one or more candidates, but to strengthen protest potential against Lukashenko in Belarus.

Lukashenko’s response

Russia’s approach is only logical given its well-established strategy towards Belarus. The Kremlin seeks to cut Belarus’s strategic autonomy by imposing an integrational paradigm (so-called close integration) or regime shift while ensuring its control over Belarusian territory. Russia finds it necessary to weaken or even destabilise the Belarusian state to become the main safeguard of security on Belarusian soil (this idea is still popular in Russia). Hence, meddling in the Belarusian election even without its own candidate is a suitable strategy for the Kremlin (this is how Moscow destabilised Belarus in 2010).

The Belarusian authorities have realised that they will not live peacefully in the current campaign. As a result, they have launched repressions against Tikhanovski and his supporters. The other two candidates have been criticised by Lukashenko but for now they are still walking free. Sergei Rumas’s government was dismissed and replaced by a siloviki-led cabinet headed by the former Chairman of the State Military Industrial Committee Roman Golovchenko. Lukashenko has made it clear he will not hand the country over to alternative candidates.

Mobilising the state apparatus and siloviki here will hit the Belarusian economy. The Belarusian government is aware of the situation but is acting short-sightedly. Its main goal is to conduct the election, keep its grip until the end of 2020 and think about next steps later on. In a worst-case scenario, some iconic liberals will get to negotiate with foreign creditors. Given the tight political calendar and prospective political turbulence in Russia, this orientation towards short-term goals can pay off. Lukashenko might be able to overcome the worst political crisis in his career.