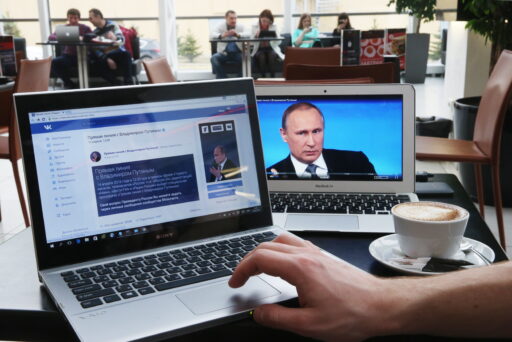

On February 29, Putin delivered his annual address to the Federal Assembly. It is not the first time that this event on the eve of elections has become an announcement of Putin’s political programme as a presidential candidate. Putin promised to raise the minimum wage from 19,000 rubles (190 euro) to 35,000 (350 euro) by 2030. To young families, he promised cheap preferential mortgages; to the elderly — active longevity programmes and good health care. To people in small towns and villages, he promised modern urban development projects; to students — new campuses and universities. To the country as a whole, he promised new roads and railways; to the regions — the cancellation of two-thirds of their debt; and to the defence sector — many military commissions. Putin tried to motivate current and potential war veterans with the federal personnel program «Time of Heroes.» The president and his speechwriters packed all his promises into six so-called «national projects.» Putin also talked about war and geopolitics, but this part was much less «social.»

Surprisingly, this time the Russian leader did without lengthy digressions about history that have accompanied all his major speeches in recent years. Most likely, Putin’s entourage — mainly the political bloc directly responsible for the election results and government officials — had a serious talk with the president and asked him to try to please the public. Before the speech, Putin had been stingy with promises, and his campaign rallies had the air of entertainment designed for one person only: the head of state himself.

It is not worth overestimating the scale of his promises — Putin is offering piecemeal measures that will fail to personally affect or help every Russian. Moreover, Putin’s promises often go either completely unfulfilled or are not fully implemented. Suffices to look at the so-called «May decrees» of 2012 — the 11 decrees with 190 goals shaping the contours of economic policy for the upcoming years some of which were later revoked by Putin himself or failed to materialize. It is likely that the same fate awaits some of this year’s promises. Perhaps some of them will be fulfilled: after all, it is not for nothing that Putin explicitly stated that the tax regime in Russia will be changed. Richer Russians and profitable companies will pay more to the treasury. Put simply, the lives of enterprising citizens and the middle class will definitely get worse, but it is far from certain that the poorer classes will live any better.

However, it is possible to name the specific beneficiaries of Putin’s message, who most likely lobbied for its main points. In this sense, Putin’s speech can be called «a message from the lobbyists.» Sergei Chemezov’s Rostec will get its piece of the cake, while Chemezov’s man — Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov — is likely to retain his control over the financial flows. The construction complex as a whole appears to be another obvious beneficiary, and more specifically, Deputy Prime Minister Marat Khusnullin who is in charge of the budget funds designated for construction and infrastructure. Roads, new university buildings, the urbanisation of villages, the repair of municipal infrastructure, the construction of houses for preferential mortgages — all of this will be overseen by Khusnullin. The personal projects of the first deputy head of the presidential administration, Sergei Kiriyenko, have also received support. The Russian Academy of National Economy and Public Administration has been promised growth and the very pool of projects suprvised by Kiriyenko will be expanded. It is not even so important where Kiriyenko will work: his people will continue to run the personnel training structures (he will retain control of Rosatom under the same scheme).

The war splits Russia in two

The longer Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine drags on, the more Russians begin to argue for an end to it, seeing Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine as misguided. At the same time, the share of those who unconditionally support continued military action is shrinking. According to the Russian Field poll, the proportion of those who advocate for peace talks between Russia and Ukraine (49%) currently exceeds the percentage of citizens who want the war to continue (40%). As soon as the name «Putin» appears in the question, the share of Russians in favour of negotiations rises to 75% – i.e. two-thirds of respondents would support the president’s decision to end the war. A third of citizens (33%) support a complete withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine. At the same time, 38% would have reversed the decision to start the war altogether, and this figure is gradually increasing over time.

The findings suggest that Russian society is currently divided into two roughly equal halves. One half wants the war to end, the other wants it to continue. Moreover, the «anti-war» camp is growing over time, while the «pro-war» audience is far from homogeneous: the majority is ready to support peace talks if the authorities decide to hold them. Citizens’ perceptions of the war clearly do not coincide with those of the authorities, who constantly speak of victories, achievements and patriotic upsurge. 49% of Russians report feeling bad when hearing the news about the war, 11% feel positive emotions, and only 5% feel «patriotic and victorious.» The most popular answer to sociologists’ questions about what goals Russia has achieved in the war is «none» with 23% saying so. Russians’ fatigue with the war is also reflected in the answers to questions about its duration: 71% of citizens say that the «special military operation» has dragged on for too long, 22% of respondents complain that the invasion of Ukraine has had a negative effect on their health (mainly psychological), 20% note the negative impact on prices. Only 3% of the respondents mention anything positive, certain «advantages» in the form of an upsurge of patriotic feelings. People have a very negative attitude towards mobilisation: 60% of respondents oppose its new wave. The wording of the question, in which Putin is the initiator of the new wave, has practically no effect on the perception of the mobilisation, with the word «Putin» is mentioned in the question, 56% of the respondents are still against mobilization.

The data from the FOM poll confirm this public mood. 30% of the respondents name the war as the most important event of the week, and their answers are mostly negative in tone: people feel sorry for the dead and the wounded. Only 3% are happy about and have at all noticed the capture of Avdeyevka by the Russian army (this event is celebrated by Russian propaganda as a great victory). The Russians are putting up a kind of shield, blocking out all news of the war, trying to ward it off.

The changes in the public mood are obvious and so are their trends: support for the war is decreasing (though not very quickly), and the share of those who want peace already outnumbers the militant part of the population. People are concerned, and not just about the war: according to the same poll conducted by the Russian Field, only 38% of Russians are not worried about rising prices. The longer the war goes on, the less people will support it. A new wave of mobilisation or serious social problems brought about by further price rises could turn the situation on its head. It is also clear that Putin has no intention of responding to public opinion, or in any way taking into account the opinion of the half of the population that wants the war to end. This was also evident in his public address to the Federal Assembly, in which Putin in one way or another evoked the war and referred to its participants as «the new elite.»

Either the president really lives in an illusory world of patriotic zeal, or he wants Russians to believe in it by constantly talking about it. In the first case, the gap between Putin and reality will continue to grow. If the second scenario is the case, we can say that the president is getting worse and worse at trying convincing Russians that they need the war.