For more than a week, the Russian President couldn’t work out his feelings — did he trust Sergey Furgal, the arrested governor of Khabarovsk Krai, or didn’t he? On July 9, Furgal was detained; it was only on July 20 when Putin finally decided that the man sitting in pre-trial detention, accused of organising contract killings, probably should not be employed as a regional leader. Furgal had been dismissed “due to a loss of confidence” (the usual wording in such circumstances); Mikhail Degtaryev, a State Duma deputy from the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) appointed as acting regional head in his place.

All this may look fairly routine for Russian politics. The president could not have acted any other way: he cannot overlook the work of his own secret services (the case against Furgal is led by the Investigative Committee and supervised by the FSB). The choice of acting regional head is also quite logical: Furgal is a member of the LDPR, so after his dismissal it was only natural that the post should have gone to a fellow party member. So there were few surprises here; a couple of days after Furgal’s arrest, LDPR party leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky said that the party expected to retain its leading position in the region, and Degtyarev’s name was first mentioned as a successor. While Telegram channels for politics watchers may have retold these events as sensational, that is more a reflection of how Russia’s Telegram channels rather than the developments themselves.

On the surface, Furgal’s dismissal looked normal. One could be forgiven for expecting that the furore in the Far Eastern region would die down, and that its inhabitants of would cast ballots in early local elections to decide whether Degtyarev was a worthy successor. But the events which have shaken the region since Degtyarev’s appointment are of such a scale that they demand a different interpretation.

An unexpected uprising

A group of investigators dispatched from the capital arrived in Khabarovsk to arrest Furgal. They handcuffed the ex-governor and returned with him to Moscow. Events such as these are normally an important component of the authorities’ PR: while idle opposition supporters raise a stink online about corruption and crime, the president rolls up his sleeves and fights it in the real world, regardless of the ranks and titles of the culprits. At least, that’s the Kremlin’s narrative. But there was a hitch.

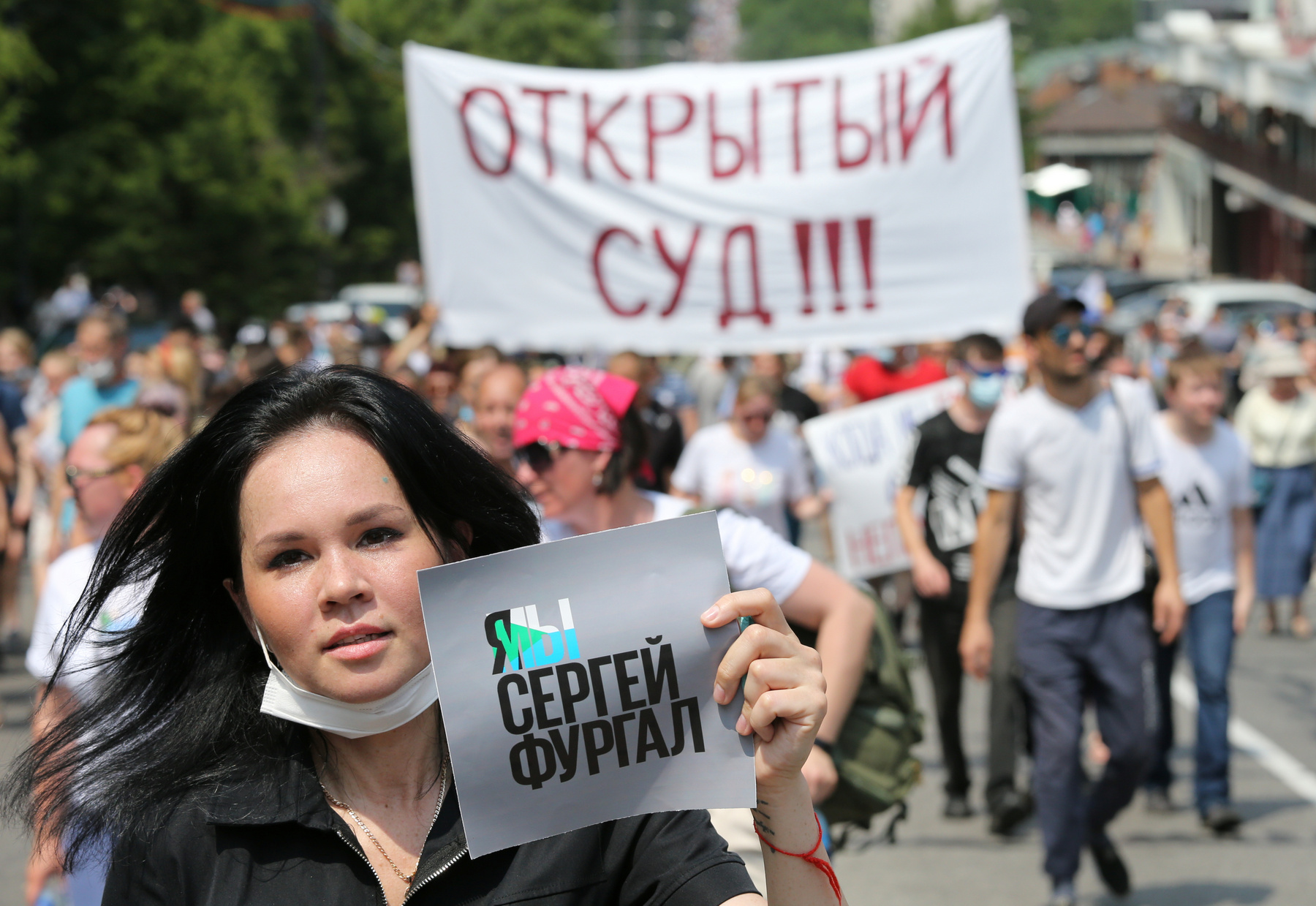

Tens of thousands of Khabarovsk residents took to the streets in spontaneous protest. It turned out that everybody understood the political context to these events: during local elections two years ago, Furgal beat United Russia candidate Vyacheslav Shport. Facing a member of the ruling party, Furgal should not have won under any circumstances. The autumn of 2018 had been an unpleasant time for the Kremlin: after an extremely unpopular pension reform, candidates from United Russia lost in several regional elections. It was an unprecedented defeat for the ruling party. However, the defeat itself was only half the problem. In subsequent years, Furgal became a genuinely popular politician in the region and was held in high esteem by locals — it seemed that he even surpassed Vladimir Putin’s approval ratings. The means by which he achieved this result can be called populist — he allocated funds for hot means for schoolchildren, auctioned a yacht owned by the regional administration, and curbed bureaucrats’ appetites for budgetary funds.

Such popular support is important. It is particularly important given that there are almost no United Russia members left in the Khabarovsk regional parliament. Furthermore, 37 percent of Khabarovsk region residents voted against the proposed constitutional amendments during the referendum — which was undoubtedly Putin’s main political project. Moreover, the region’s turnout at the referendum was extremely low — only Kamchatka was less engaged. For the federal centre, the consequences here were clear: the head of the region had neglected his most important task. He had to pay.

So it turned out that Furgal had been under surveillance for 15 years, and was essentially a mobster. Suitcases of compromising evidence turned up to support the case against him. A principled and dedicated president, went the official line, had defeated a villain who had inveigled himself into power in a distant region. But residents of Khabarovsk saw a different story: one in which the federal authorities annulled their choice of leader and high-handedly interfered in regional affairs. It is not for nothing that anti-Putin slogans were voiced during the protest rallies in Khabarovsk. It is also important to note that — however bizarre it may seem to readers unfamiliar with Russian realities — protesters who spoke to media fully acknowledged that Furgal may well have been involved in criminal activity in the past. That was normal, they admitted. Bad, but normal. Much the same can be said about any Russian politician who reaches these heights of public office. The most important distinction is not whether the politician committed these crimes, but whether the case against them is politically motivated. The people of the Khabarovsk region feel that it is — and they feel it strongly.

A terrorist and a pandemic

Moscow was at a loss. The authorities did not dare unleash the local police against the protesters. Instead, they limited themselves to spreading several theories over social media about the nature of the protest: that the rallies were not spontaneous, that they had been organised by Furgal’s stooges, and that the latter were being helped by Alexey Navalny. They alleged that very few people had come out in support of Furgal, and that everybody who did would probably catch COVID-19 and end up in a morgue. The anti-Putin slogans, they claimed, were invented by opposition troublemakers in Moscow, and were never heard in Khabarovsk. Meanwhile, the state television channels simply ignored it all.

It all looked pitiful. In response, the internet was immediately flooded with videos clearly demonstrating the contrary: that large crowds were on the streets, clearly chanting slogans against Putin. But the Kremlin’s ideologists simply had no other tricks up their sleeves.

All leading politicians, including the “systemic opposition” were at a loss. For all his indignant bluster in the Duma, Zhirinovsky stressed that the LDPR had nothing to do with street protests and urged Russians not to take part in them. Furgal himself said the same through his lawyer — in his difficult circumstances, mass popular support is certainly not a plus (something which he certainly realises better than anybody else.)

But local elites decided to support the protesters. Elena Greshnyakova, a senator from the Khabarovsk region, told the Federation Council that the brazen and offensive form of Furgal’s arrest had greatly angered people in the region. She then described pro-Kremlin journalists who had declared Furgal a criminal as “provocateurs”.

Khabarovsk continued to protest. Security forces from other regions were brought to the city (local police, it was supposed, were not to be trusted), but they still did not disperse the marches in support of Furgal. The result was too unpredictable. Meanwhile, political talk shows on state television focused on everything and anything else — Ukraine (as always), the pandemic, even a sexual harassment scandal which had arisen in Moscow’s opposition journalism circles — but not Khabarovsk. As the demonstrations continued, the city and its surrounding region appeared to have disappeared from television coverage of Russia.

Over the course of a week of protests, political strategists from Moscow came up with two proposals to cool things down. Firstly, news agencies started to report that the Khabarovsk region was the only area of the country where COVID-19 was growing. Secondly, the FSB announced that it had foiled an attempted terrorist attack: allegedly, a radical Islamist had planned to carry out a suicide bombing at one of the protest marches. The first approach was in vain, as official COVID-19 statistics are not widely believed in Russia (not without reason). The second approach also looked a little threadbare; when a video of the detained suspect was released, it was noted that he had turned up with a flag of a banned extremist organisation (which already looked a little improbable). Furthermore, the Arabic writing on the flag included numerous mistakes.

These attempts to frighten the public spectacularly backfired. In fact, they resulted in a huge demonstration on July 18. According to official data, 12,000 people attended. Protesters’ most optimistic estimates put the number at 50,000. For a city with a population of 600,000, these are significant numbers. Protests in support of the Khabarovsk residents were soon held in other cities across the region, and even in other regions in Russia’s Far East. These may not have been large, but their existence is important.

It was then that the Russia-24 state television channel broadcast a report on the protests, portraying it as an attempt by a handful of opposition bloggers who had arrived from outside the region to stir trouble. That is to say, a crowd of 50,000 individual opposition bloggers.

The Kremlin’s attempts to ignore the obvious now rivalled Gogol in their absurdity.

The Kremlin’s strategy

This is the background for Degtyarev’s appointment. Putin appears to be pretending as though nothing important has happened: here’s a new acting governor, then there’ll be elections where you can decide whether he suits you or not. As for Furgal, against whom serious charges have been raised, let the court deal with him. That is, assuming that we have a transparent justice system, that the case against Furgal is not politically motivated, that the elections will also be conducted fairly, and that the LDPR party serves anything but a decorative purpose.

So there are a lot of assumptions at play. But much the same can be said about the protesters in Khabarovsk, who act as though they lived in a country where the preferences of the public is important and whose citizens have rights. Imitation clashes against imitation. A false state meets a doomed civil society.

The Kremlin’s strategy is clear: local elites will now start to negotiate with the new interim governor. They can do nothing else; it makes no sense for them to put everything on the line for the sake of a person whose release from pre-trial detention is impossible and whose acquittal is extremely doubtful. Ordinary people will get tired of marching the streets and return to their normal lives. Everything will settle down of its own accord, and there will be a period of calm before the local elections which may enable them to be held without conflict.

Furgal’s arrest is a signal to political forces in the regions: the Kremlin will no longer tolerate surprises in gubernatorial elections. It can find compromising evidence on anyone, and the consequences for uninvited winners will be serious. From this perspective, Degtyarev is an excellent candidate: a native of the city of Samara on the Volga River, he has scant connections in the Khabarovsk region and little real political experience. He was a member of the odious pro-Kremlin youth movement Walking Together, then joined the LDPR, and became a State Duma deputy. As an official, he became known for his more colourful initiatives (for example, he suggested painting the Kremlin white and decorating Russian passports with portraits of prominent historical figures). On one occasion, he took part in a fierce election campaign: in 2013 he ran for Mayor of Moscow, just as Alexey Navalny was attempting to oust Sergey Sobyanin. In the end, he gained less than three percent of the vote.

In Khabarovsk, the formalities have been met. Its residents voted for a representative of the LDPR as governor, and now the region is again run by a party stalwart. Their future prospects are not to be envied. The people of the Khabarovsk region will have to choose between this irrelevant newcomer who enjoys no local support (though as a member of a nominal opposition party, will personify the opposition vote) and some more or less agreeable representative of United Russia.

A broken television

With regional elections on the horizon, a campaign is already underway to quash any threats to a favourable outcome for the authorities. After the new constitutional amendments were passed, a law was adopted which enables elections of any scale to be held within three days (which will naturally complicate public oversight over the implementation of voting procedure). There are also new initiatives to interfere with the work of election observers. The experience of Furgal’s arrest shows that the Kremlin will consistent rely on outsiders to the regions they govern, and who lack any real local support.

Nevertheless, it is not only the Kremlin which has drawn conclusions from the events in Khabarovsk. It is obvious that Putin’s political system simply freezes or doubles down when faced with mass protest. It is a system which permits no attempts at dialogue and does not know how to seek compromises. In the future, these facets will become serious problems to the system, capable of creating real threats.

So if it is possible to immediately respond to a protest with a wave of repression, what need is there to search for other answers? In Moscow, for example, solitary protests are held every day in connection with various political outrages. The police deal with these citizens as they usually do — with a response which is absolutely illegal. They can do this because there are only a handful of these solitary protesters. But in Khabarovsk, where the protests are large and the extent of the loyalty of local security officials is not at all clear, nobody dares to disperse the crowds.

What can be said with some certainty is that as soon as this protest wave wanes (and it will wane), criminal cases will be brought against the most active protesters. Russia’s political system simply does not know how to act any other way, and it will certainly follow standard operating procedure.

What can also be inferred from the protests in Khabarovsk is that in Russia, television has lost to the internet. Hushing up a topic on television is no longer the perfect cover-up it once was; there are more than enough alternative sources of information. The propaganda machine which has been under construction for two decades has suffered a serious malfunction. That could mean that hard times lie ahead for Russia’s internet — the state could be tempted to launch another “crusade” against it. The Russian authorities understand their weaknesses all too well, and will defend themselves as best they can.