The mid-20th century saw a grim proliferation of sites of mass captivity. The Soviet Gulag and the Nazi concentration camps are the best known. Preceding those were major instances elsewhere of mass incarceration, such as the ‘reconcentración‘ camps of the Spanish American War, or the ‘internment’ and ‘transit’ camps of the Boer War.

During the century’s two world wars, a range of camps sprang up for ‘enemy aliens’, for prisoners of war, and for displaced persons.

On other continents, there were other forms of mass incarceration, at times for other reasons. In 1915, and again in 1932, concentration camps were built in the Brazilian region of Ceará. These so called ‘poverty corrals’ were enclosures to prevent the rural poor seeking a better life in the cities. According to Raphael Tsavkko Garcia, «The purpose of the camps and their locations was to prevent people from reaching the capital, but they also were used as justification of ‘modernization’ and ‘beautification’ of the city based on the idea of social Darwinism or the ‘survival of the fittest,’ meaning that certain people were innately better than others, and the deep-rooted prejudice that rural populations would be lazy and less productive, and thus, responsible for their own situation.»

One of the many shocks of the breakup of Yugoslavia was the appearance of concentration camps in Bosnia in early 1992. The world was horrified by pictures of lines of emaciated men with shaved heads — surely not the return of concentration camps in Europe? Over the course of three years, hundreds of sites would be used as camps in Bosnia. Some, such as Omarska, would gain international name recognition and justified notoriety. The sites ranged from military facilities, to hotels, to schoolhouses. The practices of abuse and violence were a constant, irrespective of the building.

The large-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces in February 2022 has brought so called ‘filtration camps’ into public scrutiny. The term has been previously used in Russia’s two wars in Chechenia, but it is of Stalinist vintage.

In 1945, over 5 million Soviet citizens were outside of the USSR’s western border. These Soviets comprised survivors of prisoner of war camps and slave labour programmes, collaborators (both coerced and voluntary), and various émigré civilians. Repatriated with or without their consent, they were treated with deep suspicion, and placed in ‘special NKVD camps’. Considered distinct from the Gulag camps, the filtration camps nonetheless resembled them, and were typically placed near industrial centers for which the internees could provide free labor while their cases were being processed. In contrast to the Gulag, those filtration camps were dismantled in 1946.

There is now a series of these camps in areas of Ukraine that are occupied and illegally annexed by Russia. Bodies such as the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group and the Yale Humanitarian Research Lab have been trying to monitor the activities of these camps as accurately as possible with the information available.

The Yale HRL published a report in August 2022 asserting ‘with high confidence’ the existence of 21 filtration camps in the Donetsk oblast. They further differentiate four distinct, if related, functions; registration, holding, secondary interrogation, and detention.

The Russian rationale for the filtration process is to find and ‘detain all bandits and fascists’. What this means in practice is the arbitrary arrest and detention of huge numbers of Ukrainian civilians.

Men are searched for any tattoos that might show political allegiance, or telltale bruises that might indicate military action. Phone contents are searched, personal data taken, and intimidating questions are fired at detainees in an effort to detect political loyalty. People can be held for up to 30 days — yet despite horrific conditions, the Russians consider these camps to be places of ‘administrative detention’, not punishment.

The Compatriot program

For human right activist Pavel Lisyansky, these camps are worryingly similar to those established by the Chinese government to ‘reeducate’ Uyghurs. The Russian reeducation program is called — seriously — ‘denazification’. In an interview in Current Time, Lisyansky further connects this forced population displacement with the Russian Federation’s ‘Compatriot’ (sootechestvenniki) programme. This is a government effort to extend Russian influence over its minority populations in neighboring countries — the so-called Ruskii Mir, or even to repatriate Russians who live outside its borders.

However, for Lisyansky, sootechestvenniki is a grubby racist effort to repopulate distant rural areas of Russia with Slavonic looking people, as a counter force to ethnic minorities. So, ‘Forced resettlement in the East’ is the order of the day; Europe has seen this before.

Official, unofficial

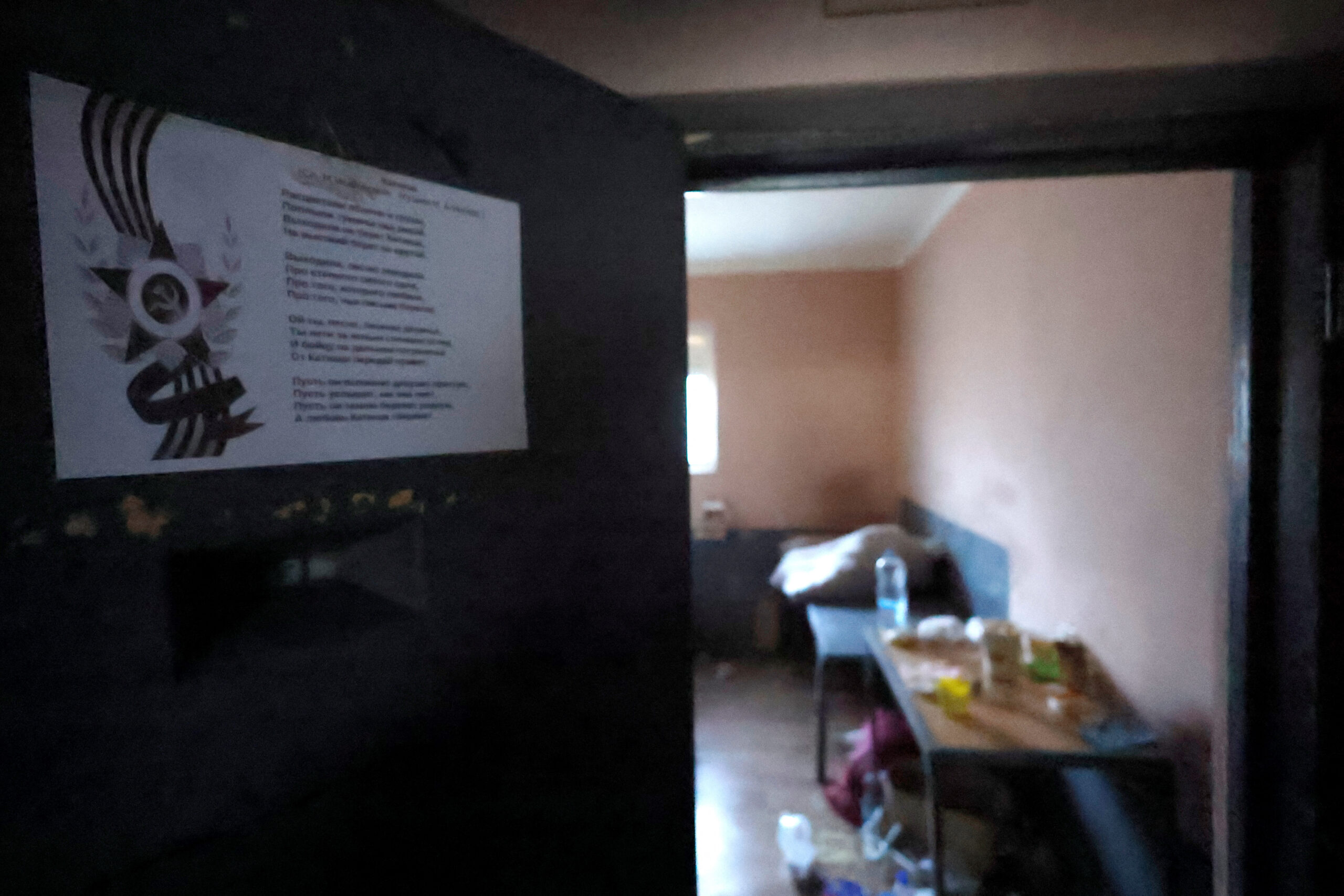

The Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group study found that Russia’s filtration sites can be divided into official and unofficial ones. The official sites include prisons, schools, and administrative buildings, places that are somewhat suited to human presence. That said, it is worth keeping in mind that one such official site was Olenevka prison, which was destroyed in July with the loss of over 50 lives.

As for unofficial sites, they include cellars, garages, sheds, places totally unfit for human habitation, let alone over a longer term. They lack even basics like lights, water, heating, and toilet facilities. Human Rights Watch published a report on this in September 2022.

‘In the villages of Bezimenne and Kozatske in the DNR, almost 200 people were effectively interned after they completed the filtration process and had received «filtration receipts,» indicating that they had successfully completed the process. For over 40 days, DNR personnel refused to return their passports and prevented them from leaving the village, where they sheltered in local schools or a cultural center in unsanitary conditions with meager food rations.’

The same report interviewed people who fled Mariupol; ‘Many described the fear, desperation, and helplessness they felt as they traveled to the filtration points. They did not know what lay ahead, but they knew that returning to the horror of Mariupol was not an option, and they believed the only way they would be allowed to flee the hostilities and danger was to undergo the process.’

An axe with two blades

The filtration process presents not one, but two horrible options. Not to pass filtration means imprisonment, torture, even execution. Passing filtration however, is not a reason for relief. People are issued their «filtration receipt» proving they have passed. However, they are then immediately at risk of deportation to other Russian-controlled regions, or even deep into the Russian interior. According to the Yale HRL report, «Witnesses describe being coerced, told they do not have any other option, or misled about their final destination, while others go voluntarily.»

According to Reuters, as of late September 2022, between 900,000 and 1.6 million Ukrainians had been forcefully deported to Russia. This figure includes a large number of children. Russia has its own numbers, admitting that 400 Ukrainian children have been adopted by Russian families — a ridiculously low figure (see the Guardian of Jan 5, 2023). The campaign is intended to demonstrate the defenselessness and vulnerability of Ukrainians as a group, and even to deny their nationality. The practice is widespread and systematic. The vast majority of people who have found themselves in the occupied territories, or in territories through which Russian troops have passed, have been victims of filtration.

Given that the screening procedure is not legally regulated and does not guarantee rights, it is impossible to predict the fate of people who have been filtered and deported. Some, not many, have been able to escape from Russia. Typically, those who escape have financial means and a personal network of relatives and volunteers to help them. For poorer people, this is not an option, they stay where are placed by Russian authorities.

We believe filtration is a uniquely horrific practice, a form of hybrid genocide. Failing it means detention, possible torture, even ‘disappearance’. Passing it can mean becoming a victim of a huge, vile project of ethnic cleansing.