The situation of oil supplies from Russia to China has changed significantly after 2022. Whereas before Russia could threaten to cut off oil supplies to the countries it considered «unfriendly», now China and India can stop buying oil altogether, that is bound to lead to a sharp drop in revenues for the Russian budget. This shift has profound political implications that go far beyond the «resource appendage» debate.

The past and present of an energy superpower

The term «energy superpower» has become one of the most important markers that are commonly used to describe Vladimir Putin’s first two terms in office. It is mainly understood to refer to the politicization of the energy business — and the gas sector in particularly — but it has gradually been extended to oil and oil products, which have become the subject of strategic bargaining.

In September 2006, at a meeting with participants of the Valdai Discussion Club, the president distanced himself from this definition: «If you’ve noticed, I have never referred to Russia as an energy superpower. But we do have greater possibilities than almost any other country in the world. This is an obvious fact. Everyone should understand that these are, above all, our national resources, and should not start looking at them as their own.»

Economic efficiency was replaced by plans for geopolitical supremacy, and «energy fists» became the main foreign policy instrument of the resurgent energy power.

Energy trade has not only an economic component, but also elements of political support or punishment. Such a policy usually takes place under conditions of high demand and availability of large number of potential buyers. If the political administration of a certain state X supports Russia’s foreign policy course, or has established close personal relations with its political leadership, or at least does not criticize the Kremlin — then it is possible to discuss not only a preferential supply regime, but also additional discounts and deferred payments, as well as favorable supply conditions for long-term contracts. Business logic suggests that if there is demand for your goods, you can always claim force major, «close the valve» and find another customer with whom you can discuss acceptable sales terms. Put simply, in an ideal world of fair market competition, customers seek to avoid market monopolization and diversify the pool of importers, while sellers seek to scale up their business to reach the maximum number of consumers.

With the onset of Russia’s full-scale military invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the situation has changed dramatically. Economic sanctions against Russia’s oil and gas sector by the EU and the US have led to a reorganization of export flows: the decision-making space has narrowed dramatically.

Russia no longer chooses, which consumers it will or will not supply energy resources to and on what terms: if any state wants to buy Russian oil without fear of secondary sanctions, Russia is ready to cooperate and do business. The number of loyal buyers is decreasing, the purchase of energy resources is associated with a large number of additional insurance, financial and logistical risks — in such conditions, energy buyers have every right to demand both large discounts and special terms of delivery and payment.

Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak said in an interview that China’s share of exports of oil and oil products from Russia in 2023 will be 50 per cent, while India’s share will be 40 per cent. Russia is willing to sell as much oil as its customers need, but how much oil is China willing to buy?

How much oil does China need?

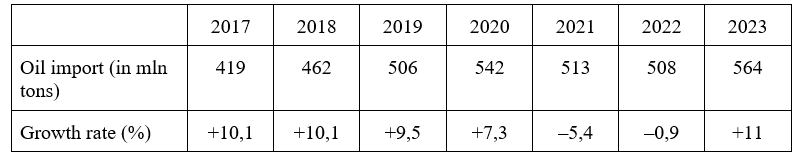

Every year since 2003, China has annually set new records for oil imports: they had been rising steadily and peaked in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2020, China increased its oil imports by 7.3% year-on-year in 2019, to a record 542 million tons. The COVID-19 pandemic largely determined the volume of purchases: China significantly reduced oil imports in early 2020 during the peak of the pandemic, and after oil prices collapsed in March, the country began to increase purchases, building oil stocks and increasing refinery utilization. In December 2020, oil prices started to return to pre-crisis levels and China reduced its oil imports.

Due to the effects of the pandemic, the severe lockdown and a whole range of accumulated domestic economic problems, the Chinese economy began to slow down, which naturally led to a decline in oil imports.

Table 1: Oil import volumes according to the data released by the General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China (GACP)

How much oil did China import in 2023?

In 2023, China imported 564 million tons of crude oil, which is 11% more than in 2022. Once again, China became the world’s top oil-importing country. However, such a volume looks rather anomalous — it corresponds neither to the level of economic recovery after the COVID-19 pandemic, nor to GDP in 2023. Yes, crude oil imports have increased, but Chinese exports in 2023 fell by 4.6% to $ 3.4 trillion for the first time since 2016, while imports fell by 5.5% to $ 2.6 trillion.

The simplest explanation is the oil-buying tactic China has already used in 2020: back then global oil prices had stabilized after a challenging 2022 and, in addition, long-term oil supply contracts had been signed, mainly with Russia and other oil-supplying countries.

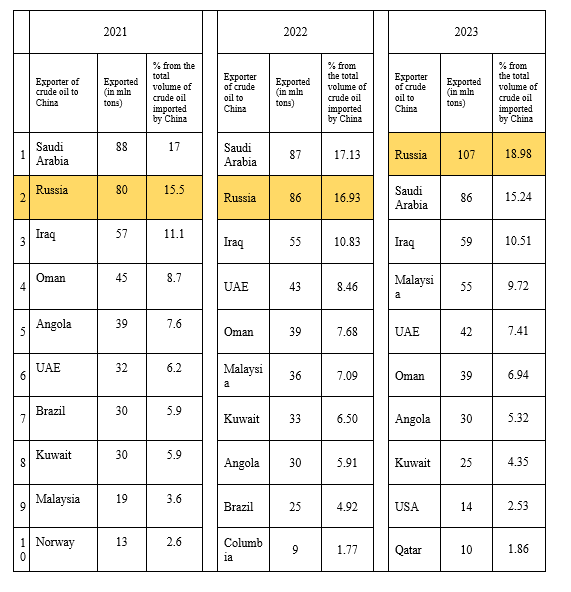

The top five supplying countries for 2023 were Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Malaysia and the UAE. The five countries exported 348.85 million tons of oil to China, accounting for 62% of China’s total imports.

Table 2. Countries exporting crude oil to the PRC in 2021−2023 according to the data released by the General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China.

How much oil will Russia export to China in 2023?

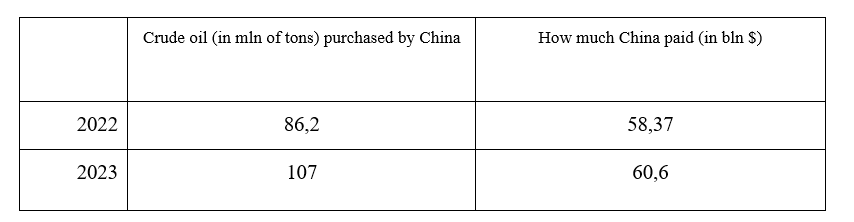

Russia supplied 107 million tonnes of oil to China in 2023, 24% more than in the previous year. The value of the supplies was $ 60.6 billion, up 3.5% year-on-year. At the 20th meeting of the Russian-Chinese Intergovernmental Commission on Energy Cooperation in December 2023, Chinese Vice Premier of the State Council Ding Xuexiang claimed that his country was ready to increase energy trade with Russia, promote cooperation in new areas and deepen the comprehensive partnership in this field. Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak said that energy cooperation between the two countries was at its highest level in history.

At the same time, China bought 86.2 million tonnes of oil from Russia in 2022, for which it paid $ 58.37 billion.

The difference in supply and payment is striking

The political consequences of the oil turn to the East

We are not experts in the oil and gas industry, but we will try to characterise the main political consequences of the growth of Russian oil exports to China.

If previously the Russian political leadership used to threaten to cut off gas or oil supplies to the countries it deemed «unfriendly», the situation after 2022 is radically different. Now India and China can threaten Russia to stop buying oil on terms that they find unfavourable. The situation on supply terms could be even more dramatic if India and China could agree among themselves to get additional preferences as key buyers. However, the complex economic and political contradictions between India and China have so far left Russia room to manoeuvre.

China has seized the opportunity to ramp up oil imports from Russia in 2023, but the next logical question is how much oil can/will China buy in the future? The Chinese economy is not growing at the rate it boasted in the very early 2000s; currently, the Chinese economy does not need any more oil than it already imports.

The next question is competition for the Chinese market. Neither Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates nor other oil exporters are abandoning the Chinese market and are planning to either maintain or increase existing supplies. For Russia to export more oil, other countries will have to export less. Alternatively, Russia should create conditions that allow it to grab an even larger share of the Chinese market. But do other oil exporters agree?

One such competitor, besides Saudi Arabia, is Iran. Attentive readers will have noticed that Iran does not figure in the tables above: apart from a few cargoes in December 2021 and January 2022, the General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China has not recorded any direct imports from Iran since December 2020. Note Malaysia — most of the Iranian oil imported into China is labelled as coming from Malaysia or other Middle Eastern countries. The oil is transported by a «grey fleet» of older tankers that switch off their transponders when loading in Iranian ports to avoid detection. The Iranian ships can be tracked by satellite near ports in Oman, the United Arab Emirates and Malaysia, from where they sail to ports in Shandong province in China. Iran and Russia are playing catch-up: to maintain and possibly increase their market share in China, they need to lower prices.

Besides prices transport infrastructure and a convenient logistics chain are also important: this is an open question, controlled less by China than by the suppliers interested in it. How can large volumes of oil be delivered to China quickly and safely?

A situation in which Russia, for example, could take control of a third of China’s oil imports also seems unlikely today. China has seen how quickly Russia can cut off energy supplies and turn off the oil and gas tap in a matter of hours and China will not take the risk entailed in the monopolization of the energy market. Why import oil exclusively from Russia when you can play on the contradictions of Iran, Russia and other suppliers to get ever more favourable discounts?

China understands the size and attractiveness of its own market. And if Russia used oil and gas supplies as a tool of foreign policy pressure, China is using oil import quotas for Chinese refineries as a similar tool. According to Bloomberg, their volume has increased by 60 per cent this year compared to 2023 — quotas for one year were issued in January. Obviously, the fight for them among oil-exporting countries will only intensify.

To sum up, it is worth recalling Vladimir Putin’s statements. In 2006, in a speech at the Sochi Summit, explaining why Russia was in no hurry to join the Energy Charter, Putin noted: «…we need to understand what we will get in return. This is easy to understand if you remember our childhood. You would go out into the yard, you would have a candy in your hand, and people would say to you: ‘Give me your candy. You would clench it in your sweaty fist: „And what will you give me in return?“ We want to know: what are they giving us in return?»

The volume of energy supplies to China will increase, but not by much: the Chinese will continue to seek diversification of suppliers, and the Chinese economic model no longer requires so much oil. China also gains a powerful lever to influence Russia’s political leadership: can China drastically reduce or increase the volume of supplies? Can China buy oil at a deep discount? Can China control payment instruments and currency used to pay for supplies? All these questions can be answered in the affirmative. What can Russia do in response? It is no longer possible to «close the valve» and switch to another consumer.