Russia and Ukraine have been fighting a widening campaign of air raids, using drones and missiles to target military and dual-use infrastructure. The air war has only intensified in the last few months. Both Russia and Ukraine are quantitatively increasing the tempo and breadth of strikes using drones and missiles. The mass adoption of one-way attack drones has been the primary facilitator of the current trend of larger and more frequent strikes. Russia still has an overwhelming advantage in the use of conventionally armed cruise and ballistic missiles, which are increasing in number as the war continues. However, while the number of Russian missile strikes is increasing, the number of missiles per individual salvo does not appear to be increasing over the course of the war, only the frequency of strikes. Publicly available data shows Ukraine is launching an increasingly aggressive campaign to target this same missile launch and production capacity.

Trends in Russian Strikes

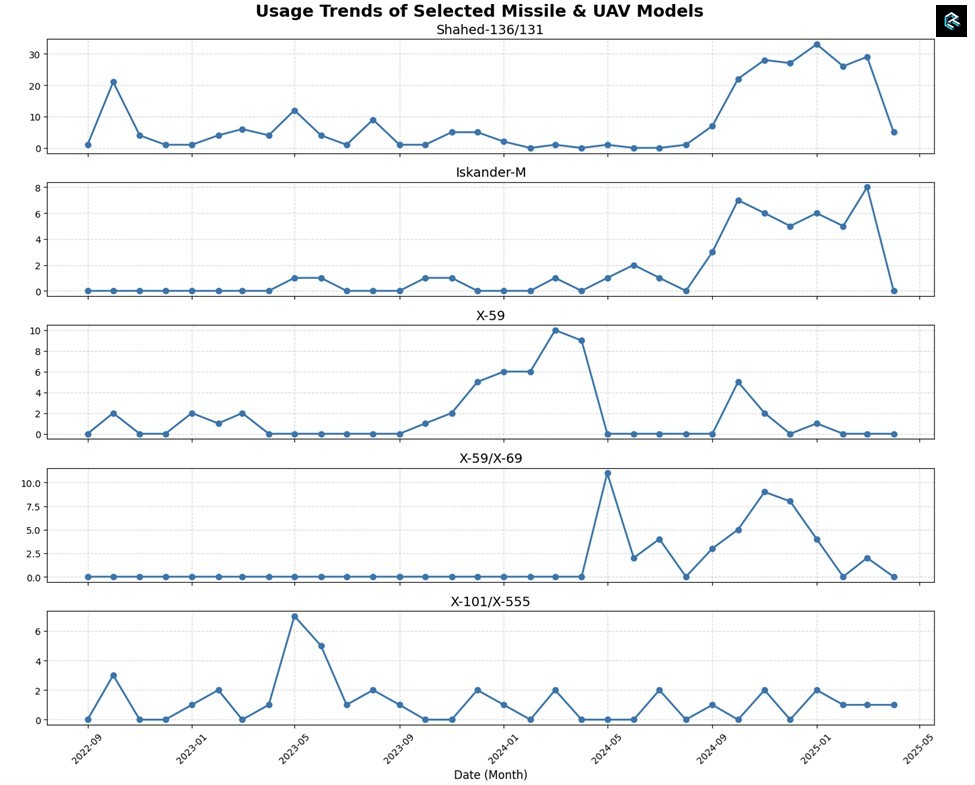

Since Autumn 2024, data compiled by Ukrainian researchers shows a massive uptick in the usage of one-way attack drones based on Iranian models. The trend is for consistent strikes, almost daily, starting in late 2024 and continuing into early 2025. This coincides with a noticeable increase in the number of strikes using Iskander-series ballistic missiles in the same time period. While throughout late 2022, all of 2023, and early 2024, reported strikes rarely rose above monthly, in late 2024, Iskander strikes began occurring 5−8 times a month.

Strikes using cruise missiles, the Kh-59, Kh-69, Kh-101, and Kh-555 series, ebb and flow. Strikes with cruise missiles in the Kh-59 and Kh-69 families began increasing in the winter months of late 2023 and early 2024, peaking at upwards of 10 strikes per month in Spring 2024, falling during the summer, and picking up pace again in Autumn 2024 and Winter 2025. Usage of Kh-101 and Kh-555 family cruise missiles has been constant but peaked in Spring 2023 with at least seven strikes in May of that year.

This data is useful for looking at the number of strikes but does not shed light on the density of strikes or the number of munitions used in a given day’s series of air strikes. The Russian military, like other militaries, will use different munitions and different densities of munitions for different targets. These different targets, with their different munitions packages, are recorded by Ukrainian officials and media only as the sum of all strikes in a given day. Classification and secrecy by the Ukrainian side on what military sites are being hit make granular analysis of strikes against individual targets impossible using open data, but the density of munitions on any given day can be scrutinized and mapped.

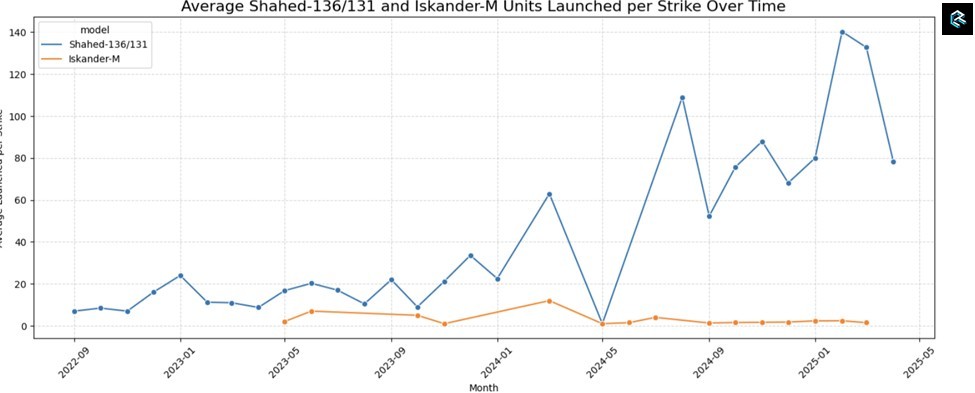

Scrutiny of density per average daily strike is useful in showing which munitions have peaked or become more prominent. The publicly reported data on the density of munitions used per day is less complete than the reported number of daily strikes but is still useful when averaged by month. For example, while the number of daily average Iskander strikes has increased since late 2024, the number of actual ballistic missiles used has stayed relatively constant. Discounting the gaps in this information for 2022 and the opening stages of the war, this shows that while the Russian military may be increasing usage of these ballistic missiles, they cannot or are choosing not to do large daily salvos.

The opposite can be said for the «Shahed» family of drones, which includes Russia’s domestically produced copy — the Geran. Here, in addition to a massive increase in daily strikes, there is a quantitative increase in the raw number of these munitions being used in average daily strikes. Even when accounting for overreporting by Ukrainian air-defense teams or misidentification of «Shaheds,» there is clearly a major quantitative uptick.

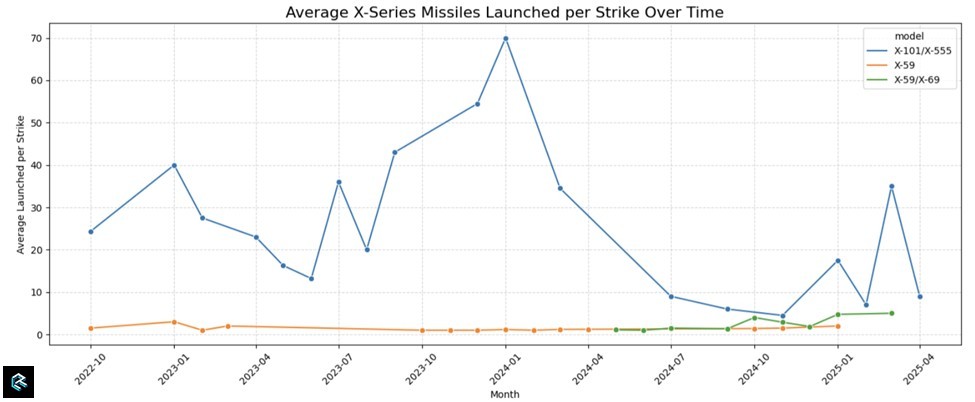

The same cannot be said for Russia’s cruise missiles, which saw a peak in the density of munitions used during the Winter of 2022/2023. This was made up almost exclusively of missiles the Ukrainians record as being in the Kh-101/Kh-555 family. This peaked with an average (reported) density of 50−70 missiles launched per day in December 2022 and January 2023. This rate is completely unsustainable and helps explain the 0−2 strikes per month on average since then.

The Kh-59 and Kh-69, which can be launched from fighter jets rather than large missile carrying bombers, appear to be used more as a precise weapon akin to the Iskander, with salvos never averaging above five per day in late 2024. Before that, salvos averaged less than five used per daily strike. In contrast to the «Shahed» family, which runs on piston engines similar to civilian aircraft rather than turbojet engines, the modernized Kh-59 and Kh-69 fleet runs on. As such, production lines on these particular weapons may be cannibalized by the requirements for other missile systems.

Ukrainian Counterstrikes

One salient factor, which cannot be ignored for understanding Russia’s ability to launch larger salvos, is the pressure Ukraine is putting on Russia’s relatively small fleet of missile-carrying bombers, the factories that service them, and the airfields that host them in European Russia. By doing so, Ukraine is constraining the number of airplanes in the air able to launch missiles at any single time.

The Kh-101 and Kh-555 cruise missiles are non-nuclear, air launched siblings of Russia’s air-launched nuclear cruise missiles. Because of this lineage, they are launched from older, larger Tupolev-produced strategic bombers produced during the Soviet period. Rather than build new airframes, Russia has focused instead on maintaining and modernizing this fleet. Serial production on the Tu-22 for example, ended in the 1980s.

The infrastructure for these aircraft is concentrated at a few key factories specialized in maintaining the engines and airframes. Much of this maintenance on the Tu-22 and Tu-160 missile carriers is done in well-known factories in European Russia. On at least one occasion in the database, Ukrainian special services took credit for a drone attack on the Gorbunov aircraft plant in Kazan, where much of this maintenance work on the Tu-22 and Tu-160 is done.

Engines, which are often the most expensive and complex part of an aircraft, for the Tu-22, Tu-160, plus the larger Tu-95 missile carriers, are worked on at ODK Kuznetsov in Samara. In the collected data, Ukraine has attacked the Samara region seven times with drones — always aimed at oil and energy infrastructure rather than military plants, but key plants like this are increasingly in range of Ukraine’s strike capacity.

These bombers, designed with nuclear war in mind, are located at a handful of relatively unprotected airfields that, knowing they are targeted by nuclear weapons, do not have robust protection against conventional threats. Engels-2 is one of these bases and the most popular identified target of Ukrainian drones. Located one oblast over from the engine maintenance and production facility for the bombers stationed there, Engels has been hit at least 11 times in the recorded data. Engels-2 was struck dramatically in March 2025, when a large ammunition dump for the base was targeted. Ukraine has attacked Engels-2’s sister base in Murmansk at least twice, as the Russian air force tried to move some aircraft there for greater protection. Reliance on relatively unprotected older Soviet bases designed for nuclear, rather than protracted conventional war, has made these drone attacks viable for Ukraine.

Ukraine has also targeted production centers and alleged production centers of «Shahed» series drones. However, given the location of these facilities deeper inside Russia, these are fewer than the attacks on air bases in other parts of Russia. For example, the database has one incident of an attack by Ukraine on the much-publicized facility in Yelabuga with a modified light aircraft. The database also has one attack on the Kupol defense plant in Izhevsk, where Ukraine alleges Russia has started a new production line.

Further Trends in Ukrainian Strikes

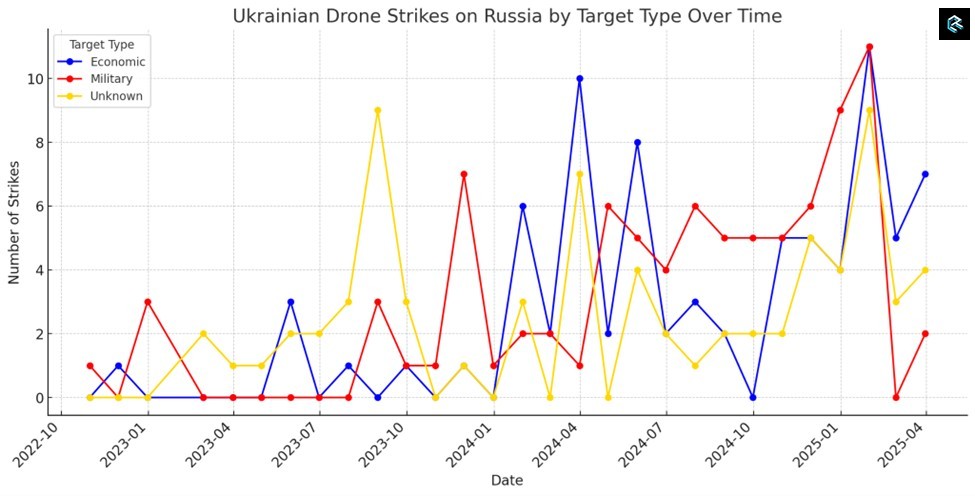

Ukraine has focused on a combination of military and economic targets in Russia. The former are a combination of airfields, military production facilities, training grounds, and dual-use production facilities such as powder production facilities. The economic targets have overwhelmingly been parts of Russia’s energy export infrastructure, such as fuel facilities and pipelines. One gap in the data is that during large attacks, particularly on Moscow, little information is available on what is being targeted, so specific information on successful strikes is biased toward targets outside of Moscow and Moscow oblast.

The database codes 79 targets as economic, 85 as military, and 73 as unknown. When the dates are plotted, the data shows that the highest portion of «unknown» targets were strikes that occurred in late 2023 and 2024. From there, a spike of strikes on economic targets began in Spring 2024. The biggest trendline is that as time has gone on, Ukraine has gotten much better at targeting Russia’s military facilities deep inside Russia. Early 2025 shows strikes on all three categories of target by Ukraine reaching new highs, indicating an increased confidence and capacity.

Gaps in reporting mean that a concrete count of which oblasts were targeted by Ukrainian salvos is not precise. However, a general trend is that the oblasts reported most frequently as targets of Ukrainian air raids are those in Southwestern Russia near the Ukrainian border. Belgorod, Kursk, Bryansk, Oryol, and Voronezh oblasts are some of the most common targets — particularly for strikes on economic targets. Individual strikes in Chechnya and specific training facilities deeper in Russia appear, but not with the same breadth. Ukraine is openly working on various projects to strike deeper into Russia with new experimental weapons systems.

Data and Methodology

This article uses a custom-built dataset of Ukrainian strikes on Russian targets and publicly maintained databases of Russian strikes on Ukraine maintained by Ukrainian volunteers, used here under Creative Commons.

The dataset of Ukrainian strikes against Russia covers recorded strikes from October 2022 to the end of March 2025, covering at least 237 incidents. The Russian strike data covers strikes from September 2022 to April 2025, covering thousands of incidents. The noticeable gap from February 2022 to autumn 2022 is more significant methodologically for the Russian side but is still useful in showing how reported strikes have evolved.