Rosneft has been gambling in Venezuela over the last decade, with CEO Igor Sechin leading the drive for closer ties between Moscow and Caracas. Venezuela’s oil rich fields were seen as a key area of expansion for the firm. In August 2017, Sechin declared “we will never leave from there. No one can chase us out. We will work with Venezuela and we will raise the level of cooperation.”

Rosneft certainly has not left; but Venezuela’s oil output has continued to suffer. Rosneft’s joint ventures with Venezuelan state oil firm PDVSA, including the Petromonagas upgrader that performs a key role in blending Venezuela’s heavy crude into a product easier to refine and handle, have also suffered. Even so, Rosneft’s support for the Maduro regime has only escalated. The firm has even stepped in to ship naphtha, a key diluent in the upgrading process, from Russia to Caracas and has become Venezuela’s sole source of imported refined petroleum.

Yet nearly every other Russian-Venezuelan joint venture has collapsed amid the economic crisis and US sanctions action. Russian oil firm Lukoil pulled out of the same naphtha trade. Lukoil was concerned over how tightened US sanctions on the firm could be applied. VTB and Gazprombank have moved to dump their shares in the bank Evrofinance Mosnarbank, 49.9 per cent owned by the Venezuelan regime, onto state property agency, Rosimushchestvo. Gazprombank separately has lost around US$1bln from its failed Petrozamora investment. Even Rostec, the only other major Russian firm still operating in Venezuela, acknowledges the major challenges the country faces. Its CEO Sergei Chemezov told RBC on 16 September that plans to build two long-delayed factories in the country were facing continued challenges from blackouts and the unavailability of supplies.

Rosneft meanwhile has continued its support of PDVSA and the Venezuelan regime. Some dub Sechin as the savior of Caracas, both in Russia and the West. Its support has continued despite regular tightening of US sanctions and despite repeated rumors that Washington would tighten sanctions on the firm over its support for the regime of President Nicolas Maduro. Special Envoy to Venezuela Eliot Abrams, however, said in late August no such plans were in place, reiterating these comments two weeks later.

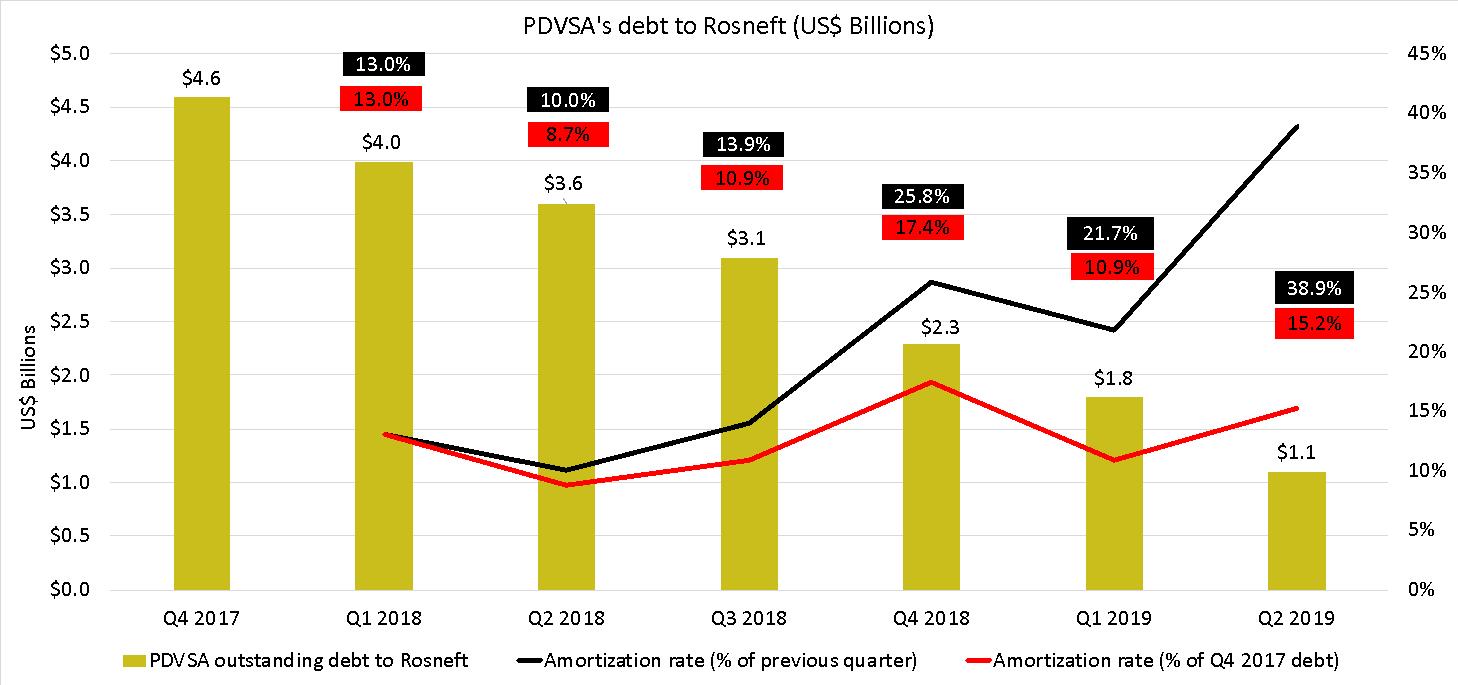

But Abrams did warn that Washington would have to look at Rosneft’s activity, a key warning. After all, the clock is running down on the tactic Rosneft has employed to continue handling Venezuelan oil despite Washington’s sanctions regime: the firm has stated that all of the Venezuelan crude it has received has been to service pre-paid agreements struck before US sanctions hindered such business. A look at Rosneft’s financials provides evidence to back up this claim. According to its quarterly reports, outstanding debt on these contracts has fallen sharply, from US$4.6 billion at the end of 2017, to US$1.1 billion at the end of this June.

There are two important aspects to this. First, it demonstrates that Rosneft’s US$1.5bln loan to PDVSA – issued at the end of 2016 and secured over a 49.9% stake in US oil refiner and marketer CITGO – has begun to amortize. There had been concerns that Rosneft could use this pledge to try to involve itself in the already extremely messy spat over CITGO’s future. Doing so would have evoked Congressional ire, though until the loan is fully repaid, mistrust will linger. Yet the full repayment of the loan would raise a second, even more difficult question for Rosneft: how will it continue to ship Venezuelan oil when it is no longer taking the product as debt repayment?

Washington has been clear on how taking any oil from Venezuela that was not a repayment of previous debts would violate its sanctions policy. However, Rosneft could claim once the remaining US$1.1bln in principal is repaid that future deliveries are related interest payments. Rosneft has never publicly detailed what interest is due on the loan nor whether they are being met, or delayed, even after striking a ‘remediation agreement’ with PDVSA in May 2017. Though it has been argued that Rosneft is already skirting the spirit of sanctions, this strategy would be far more aggressive.

Rosneft may be sitting on a large pile of overdue interest from Caracas. But it remains unclear if the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), the main US sanctions authority, will simply accept an argument that future oil shipments are to pay interest due. Rosneft appears to have a strategy in place to try and pressure OFAC into approving its continued, deepening, involvement in handling Venezuelan oil: turning to yet another international partner.

Rosneft has significantly increased shipments of Venezuelan oil to India’s Nayara Energy in recent months. Formerly known as Essar, the firm controls the Vadinar refinery, India’s second largest, is 49% owned by Rosneft. These deliveries to Nayara are part of PDVSA’s debt amortization. Rosneft would be in violation of US sanctions if it continued them once PDVSA has repaid its debts to Rosneft. However, there is reason to believe that Sechin could test the waters here. He might try to continue such deliveries in the future even once the principal of PDVSA’s debt has been repaid, under the argument they represent interest payments.

Rosneft’s control of Nayara demonstrates how it has used Delhi to test the boundaries of sanctions before. There is little doubt Rosneft effectively controls Nayara, given the minority stake held by Russian firm United Capital Partners (UCP). UCP has long been linked to the Kremlin, with UCP’s director Ilya Sherbovich having sat on Rosneft’s board. VTB’s Andrei Kostin famously told Reuters that the deal was specifically structured to evade sanctions. Rosneft’s ability to avoid tighter US sanctions despite increasingly widespread recognition that its actions are more motivated by politics than its bottom line, comes in large part from the fact its foreign tie-ups insulate it.

Qatar owns 14.2% of Rosneft, while British energy giant BP owns another 19.5%. Any move against the firm would affect their bottom lines as well. And with US President Donald Trump increasingly prioritizing his relationship with India, it is easy to see him calling for a technical sanctions violation to be ignored. There is already precedent emerging for him to do so, as it appears unlikely Turkey will face sanctions for its purchase of Russia’s S-400 missile defense system despite Washington’s previous threats.

Sechin may be eyeing Delhi as his latest foreign insulation against sanctions. Visiting Delhi on 17 September, Sechin said Rosneft would be investing in expanding the Vadinar refinery. He claimed his firm was a more reliable supplier of crude than India’s existing partners, an attempt to take advantage of the Saudi disruption earlier in the week. Trump has already spent political capital getting India to comply with US sanctions on Iranian oil. Sechin appears to be betting Trump will refrain from doing so again with Venezuela.

Rosneft is willing to engage in the high-risk strategy given just how much it has plowed into Venezuela. For Sechin, the matter is personal. He has led Russia’s relationship with Venezuela since well before he assumed the helm at Rosneft. Were Rosneft’s investments to go up in smoke, Sechin, who is one of the Kremlin’s most feared powerbrokers, could be significantly weakened.

Just last year Sechin told Germany’s Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung that he saw no issues with Rosneft’s loans to PDVSA; he denied that foreign policy was a motivating factor in its business operations there. Though the loans are ostensibly being repaid, the statement is clearly laughable. On 11 September, Rosneft issued a statement defending the legality of its investments in Venezuela and decrying the “threat of sanctions.” Yet the statement was also the first time Rosneft has called for talks with Washington about its position.