One of the most shocking decisions of late 2021 was the court order to shut Russia’s oldest civil rights group, Memorial, for failing to comply with the requirements pertaining to a non-profit organisation listed as a foreign agent. According to OVD-Info (itself classified as an unregistered civil association acting as a foreign agent), in late 2021, 220 non-profit organisations, 4 associations, 67 individuals and 36 media outlets were listed as foreign agents.

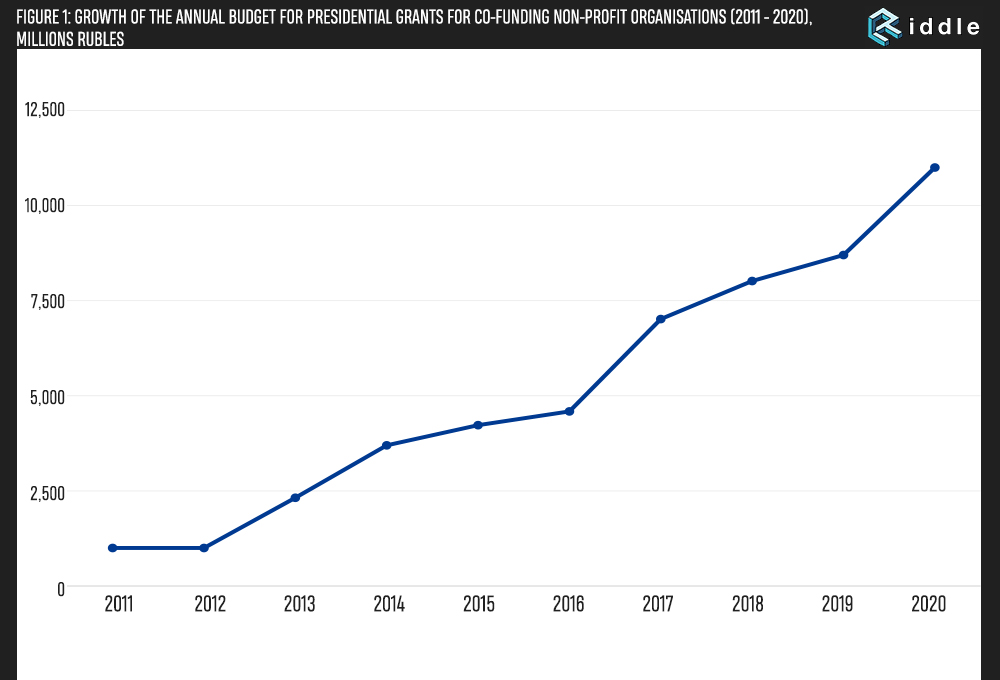

At the same time, the state had been consistently increasing its funding for the third sector: through presidential grants alone, funding rose from 1 billion roubles in 2011 to 11 billion roubles in 2020. Numerous regional and municipal grant competitions for non-profit organisations were held, and subsidies from competent ministries were also allocated more generously. Pro-governmental private foundations that had traditionally supported non-political projects also increased their support. For example, the Timchenko Foundation spent 794 million roubles on programme activities in 2018 and almost 1.7 billion roubles in 2020. The Vladimir Potanin Foundation allocated an additional 1 billion roubles to support the non-profit sector in 2020.

There is a certain logic behind the seemingly contradictory behaviour of the state which hinders the development of civil society organisations by erecting new barriers on the one hand and increases funding on the other. On the one hand, independent civic organisations pose a threat to authoritarian regimes, as they accumulate information from independent sources, monitor the implementation of legislation and critically evaluate the work of public authorities. Organisations operating in sensitive areas — human rights, elections and the quality of governance — pose a particular threat to autocracies. On the other hand, non-profit organisations provide a range of socially relevant services and enable the collection of important information about the state of affairs in individual areas. A crackdown on the former combined with promotion of the latter contributes significantly to the sustainability of autocracies.

Civil society in an authoritarian environment

Classical political science used to treat authoritarian regimes and independent civil society as antagonists: autonomous associations of citizens independent of the market and the state were considered ‘schools of democracy’ (Alexis de Tocqueville), a sphere of free rational discussion of societal issues (Jürgen Habermas) or pockets of resistance to dictatorships (John Keane). This was indeed the case of totalitarian regimes, which sought total control over all aspects of social life. However, softer autocracies prove to be much more tolerant of certain aspects of civic life for many reasons.

First, while the last two decades have seen authoritarian regimes intensify their fight against foreign funding of non-profit organisations, in some cases they have not prevented, and even encouraged, the raising of foreign funds by non-profit organisations in order to replenish the national budget with foreign currency.

Second, through the activities of non-profit organisations, autocrats can carry out unbiased monitoring of the popular sentiment and develop their feedback strategy accordingly. For example, Algeria under Abdelaziz Bouteflika used advisory boards which included representatives of civil society to collect complaints and grievances from citizens.

Third, non-profit organisations are needed by authoritarian regimes to fulfil their social duties while delegating some of these functions to the third sector. Carolyn Hsu notes that in China, following the Tiananmen Square protests, non-profit organisations played a significant role in promoting public reforms in education, environmental protection and poverty alleviation. In Syria, elites were willing to share responsibilities with non-profit organisations when it comes to reforms or providing routine welfare services since changes implemented through non-profit organisations are associated with lower reform-related political risks and the involvement of additional social groups with the authoritarian regime.

Fourth, research in Russia and China shows that local non-profit organisations and advisory boards operating under the auspices of the authorities serve as platforms for activists to implement their projects and voice acceptable criticism while being under control. Jörg Wischermann and colleagues have aptly called this ‘control through limited participation’.

Finally, autocracies use civil associations to fight the opposition. Researchers using Malaysia as an example have noted that if the incumbent is able to garner the support of civil associations, they can serve as a good organisational structure for campaigning and/or attracting votes from citizens susceptible to electoral clientelism. Interestingly, this can also work in the opposite direction: in order to retain power, it is important for the incumbent to prevent the opposition from gaining access to an organisational network and reputation that non-profit organisations can offer. This is why, for example, the regime of Recep Erdogan in Turkey tries to co-opt those civil society organisations that are prone to being politicised and that support the opposition. In Russia, the heads of non-profit organisations are often included on various advisory boards.

Russia’s carrot-and-stick policy

Putin’s Russia perfectly exemplifies not only the textbook counterbalancing of the carrot-and-stick approach but also other options of strategic engagement with non-profit organisations. On the one hand, the state has been steadily increasing its control over the third sector since 2006, which culminated in the so-called foreign agents law. Our 2015−2016 research, which included a series of interviews with representatives of civil society organisations, showed that organisations listed as foreign agents faced significantly more detailed reporting, changes in the attitudes of partners and state authorities, as well as higher security-related costs. Non-profit organisations not affected by the law were forced to change their sources of funding: grants from international and foreign foundations became either simply unavailable or entailed risks of being included in the register. At the same time, an analysis of the lists of foreign agents showed that non-profit organisations dealing with issues perceived by the Russian autocracy as sensitive — elections, human and minority rights, freedom of speech and the environment — have come under particular pressure.

However, along with the increased crackdown on civil society, there has been a gradual increase in state support for the third sector. The most ambitious tool included the presidential grant programme (budget funds allocated to selected non-profit organisations by a presidential decree). Grant competitions for officially registered non-profit organisations were introduced in 2007, and have been held twice a year since 2016. The total grant fund increased from 1 billion roubles in 2011 to 11 billion roubles in 2020 (Figure 1).

The presidential grants for co-funding non-profit organisations are administered under strict political supervision by the Coordinating Committee chaired by the First Deputy Head of the Presidential Administration, Sergey Kiriyenko. The Presidential Grants Fund CEO, Ilya Chukalin, has earned respect among professional non-profit organisations and can boast of experience in both the non-profit sector and public service at the Ministry of Economic Development. All Russian non-profit organisations (except for political parties and certain other organisations such as lawyers’ associations, employers’ establishments and associations) can apply for funding.

Yulia Skokova and Christian Fröhlich studied brief descriptions of applications for presidential grants and found that their content largely corresponds with conservative public discourse. We, for our part, analysed the distribution of 2017−2018 grants under the category of ‘protection of human rights and freedoms’ and concluded that the state allocates large sums to organisations loyal to the incumbent regime. Thematically, the majority of projects in this area dealt with legal education, legal aid and protection of vulnerable individuals. Some of the projects dealt with freedom of speech and civic oversight.

We measured loyalty through the involvement of the heads of non-profit organisations on governmental advisory boards, as well as their engagement with the All-Russia People’s Front (ONF) and United Russia. We found that leaders’ involvement in the ONF increased the amount of funds allocated to the organisation. At the same time, participation in the activities of the ruling party does not show a significant correlation with the size of grants. Interestingly, a positive correlation was found between the amount of grants received by a non-profit organisation and the participation of its representatives in elections in alliance with any of the parliamentary parties. We believe that this is indicative of the regime’s strategy of co-opting independent non-profit organisations through the ONF and loyal opposition parties. The regime is determined to expand its base of loyal civil society organisations without focusing solely on representatives of the ruling party. By financially encouraging the loyal opposition, which is even allowed to speak out publicly, the Russian regime manages not only to maintain a semblance of diversity but also to prevent social activists from defecting to the side of the real opposition.

Despite the blatant crackdown on civil society, the ‘stick’ is by no means the only means of governance. Presidential grants work as a ‘carrot’ in that they cover a wide range of organisations with a relatively low entry threshold. While it is impossible to find LGBT-related projects or initiatives targeting political prisoners among the applications (these are non-existent problems according to the Putin regime), the array of eligible topics is broad enough. For example, Memorial received a grant for legal aid for migrants and refugees in 2015. Our research also showed that experienced organisations receive more funding. In other words, regardless of the degree of loyalty to the authorities, the decision to allocate a grant is at least partly merit-based.

Studies, including our own research, suggest that the strategy of contemporary autocracies towards civil society is largely guided by a rational logic of maximising benefits and minimising risks. Repression is used against those non-governmental organisations which are less beneficial and highly problematic for the regime. Civil society organisations which pose minimal risks to the regime and generate benefits are encouraged to operate. Alongside these opposites, there are organisations that bear neither benefits nor costs to the regime (they are simply ignored), as well as organisations that can potentially be both beneficial and dangerous to the regime. The latter (e.g. human rights or environmental organisations) can be co-opted through various pro-government structures and kept afloat on the regime’s terms. As one of our interviewees put it, there is a certain danger in a large flow of public money to civil society organisations: ‘this is addiction, dependence on state funding; once you become accustomed to certain sources of funding, you stop looking for other options’. Accordingly, the sustainability of Russian authoritarianism rests not so much on repression as on a combination of ‘sticks’, ‘carrots’ and the co-optation of civil society.