Neo-camp is an avant-garde and in-demand style across the world today. One leading global fashion bellweather is the MET Gala, an exhibition and party developed by the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum in New York; it captures the spirit and aesthetics of the era, and this year was devoted to camp.

2019 has also been the year of camp in Russia. Glamour and conservative ‘imperial chic’ used to be the official style in Putin’s Russia of the 2000s; millennials opted, in the early part of the 2010s, for a ‘post-Soviet Gopnik’ style that is as far from both official glamour and liberal hipsterism as one can possibly get. It was precisely then that the so-called New East Style — a derivative of recycled poverty aesthetics from late Socialism (the late 1980s) and trash glamour of the early transformation (of the 1990s) — entered the avant-garde and subsequently mass world fashion. Three designers and stylists from the former Soviet Union – Gosha Rubchinskiy, Demna Gvasalia (Vetements and Balenciaga) and Lotta Volkova – were the pioneers of this metamodernist style. The transnational success of the New East/Gopnik style marked the end of the post-socialist imitation of the West; and it is directly linked to the rise of identity politics in Eastern Europe and Russia.

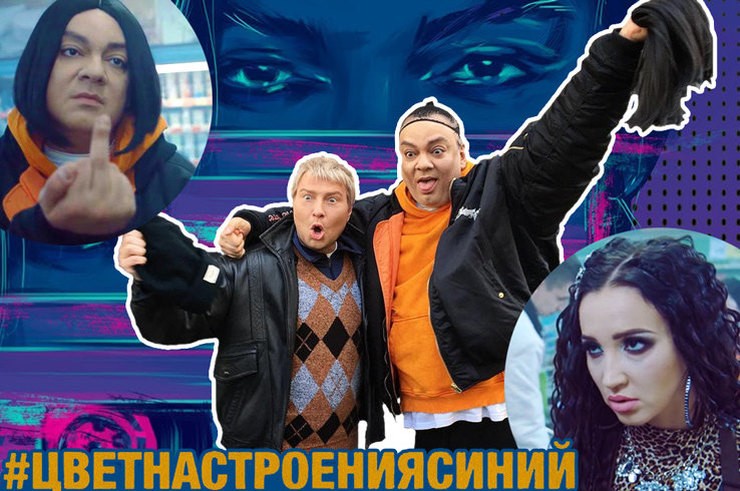

Neo-camp is a radicalised version of a generalised Russian Gopnik style. It is a triumph of excess and exaggerated bad taste that emerged full-blown in the mid-2010s. The most popular and successful representatives of Russian show business and the media exploit this particular genre: Sergey Shnurov and his band Leningrad, Alexander Nevzorov, Olga Buzova, Alexander Gudkov and the band Little Big. A number of pop stars popular in the 1990s contributed to the revival of interest in the aesthetics of those days: the ‘king of Russian trash’, Philipp Kirkorov, became an iconic figure among post-millennials after the release of his song ‘The Colour of the Mood Is Blue’ (2018), with camp and self-deprecating visual imagery.

Philipp Kirkorov, ‘The Colour of the Mood Is Blue’ (2018)

Susan Sontag, the first theoretician of camp, defined it in her essay ‘Notes on “Camp”’ (1964) as a sensibility, mood, or visual taste aimed at stylisation, exaggeration, the unnatural and extravagance. Sontag described camp as ‘the revolt of the masses’ and as a form of dandyism, as a reaction of the intellectual elite to the capture of culture by the masses, as a private code of closed communities deciphering the ambiguity of the statement: ‘camp overcomes aversion to copies’.

Sontag also linked camp to queer and gender transgression, having noted the ‘androgynous preferences’ of this aesthetics, which often go hand in hand with mannerism and hyperbolised sexuality. Camp as hyper-aestheticism and new dandyism negates not only the hierarchy of taste but also the hierarchy of morality, since the goal of camp is to enhance sensibility and tension while maintaining ironic distance.

As the sensibility and aesthetics of a new (digital and real) ‘revolt of the masses’, neo-camp of the early 21st century is associated with two main ideological shifts in recent years, i.e. the right-wing turn to populism and the queer revolution. Although these two phenomena are often described as antagonistic, they are closely interrelated. Neo-camp is the result of two types of coming out: the coming out of queer aesthetics into the gender mainstream and the coming out of the aesthetics of populism into the political mainstream. Similar to populism, the performative aspect and affectivity matter in queer art. Camp deconstructs gender stereotypes, getting rid of them through their ironic exaggeration; populism brings emotional tension, theatrical irrationality and sincere passion to politics. A parody performed by the newly elected president of Ukraine, Vladimir Zelensky, who combined queer and populism in a music video called ‘The Cossacks’ (2014), is an example of new camp politics.

‘Meanwhile in Russia’

Yet another revolution aimed at undermining the global hierarchy and cultural hegemony of the West has taken place in Russia. Russian neo-camp is a manifest criticism of the Russian neo-liberal elite’s view of the people as barbarians. Equally, it is a criticism of Russia’s reputation as the root cause of political chaos, as it has been presented in the Western media since 2014, which reached its pinnacle in 2018 in connection with Russiagate. Therefore, although Russian neo-camp is part of the entertainment industry and global exchange, it can be described as the emancipatory aesthetics of resistance to the First World, to both internal and external colonisation.

The main technique used in political neo-camp is appropriation of a popular online meme genre known as ‘Meanwhile in Russia’. This popular aesthetic and political rhetoric defines Russian identity not via history or territory (as official discourse does). Rather, it does so as an affect, as a certain political and existential emotionality that has acquired a universal dimension: ‘Russia is not a country but a state of mind’.

Thousands of music videos and photographs present Russia as a hilarious amusement park full of shameful entertainments — a zone of demodernization, absurdity, scandal and antisocial behaviour that violate all the norms of the ‘civilised world’. On the other hand, these videos present Russia not just as a rogue state or as a freak, but also as the land of unexpected and bold decisions, sincerity, vitality and freedom from repressive regimes of ‘good taste’ and ‘moral panic’.

The ‘Meanwhile in Russia’ meme. Source

Little Big: neo-camp and global chaos

The St Petersburg-based band Little Big, which became a global phenomenon in 2018 after the release of their hit song ‘Skibidi’ (218 million views on YouTube) is most consistent in its use of the technique of appropriating stereotypes of the Western view of Russia combined with self-parody of the national character.

Little Big is a Russian punk rave band founded in St Petersburg in 2013 by Ilya Prusikin. It is not just a music group, however; it is a large-scale, online multimedia art project with its own production company ClickClack (КликКлак), which allows the band to make their own viral music videos.

Ilya Prusikin, the frontman for Little Big

The band’s music videos criticise the current habit of reducing Russian culture to a set of ‘Meanwhile in Russia’ memes: the Gopnik, bears, vodka, a matryoshka, kokoshniks, earflap hats, Russian folk dance, carpets, prefabs, girls in Soviet school uniforms, beefy guys kissing their biceps, bathing in icy water, a Russian bathhouse, a pseudo-icon of the Virgin Mary in a balaclava (reference to Pussy Riot as a new Russian meme), prison tattoos and transgressive sexual objects. In musical terms, many compositions by Little Big are pastiche and a parody of the Hollywood musical image of the ‘red enemy’ and disco hits the 1970s and 1980s about the Soviet Union and Russia (such as ‘Moskau’ by Dschinghis Khan and ‘Rasputin’ by Boney M).

The song ‘Everyday I’m drinking’ (2013) — created by Prusikin together with film and music-video director Alina Pyazok (21 million YouTube views) — became their first top hit and video meme. This first music video introduces protagonists from the carnival ‘Russian world’ created by Little Big: a Gopnik with tattoos in the shape of bear toes, a creepy policeman-clown, an uber-sexy dwarf girl wearing a kokoshnik and sarafan – all of them dancing and singing in English with a pronounced Slavic accent:

Hey! Kiss my ass, world!

Here motherfucker Russia soul!

Our country in deep shit! Yo!

But I love, but I love her!No future, no rich

This is Russia, bitch!Everyday I’m drinking

Everyday I’m drinking

Everyday I’m drinking

I’m drinking everyday!

An image from the music video ‘Everyday I’m drinking’ (2013)

The song ‘With Russia from Love’ (19.5 million views on YouTube), which lent its name to the band’s first album, sets the interpretation framework for their artistic statement as a subversion of Westerners’ view of Russia:

Winter comes, they won’t get us

Share our secret, we’re kings of the great mess!

An image from the music video ‘With Russia from Love’ (2014)

Hyper-visuality and memeticity are typical of a number of other music videos created by the band, including ‘Give me your money’ (2015), the result of cooperation with one of the main representatives of avant-garde European camp, Russian-speaking Estonian Tommy Cash (44 million views on YouTube). In the video, Russia and Moscow are presented as New Mordor, the centre of all that is evil and a place where there is no boredom, where a non-stop performance of life is staged. However, the video, which is filled with a canonical set of obscene and politically incorrect memes, ends with trash aesthetics instilled in the concept of national security, and the freaks turn out to be elegant Russian intelligence agents.

An image from the music video ‘Give me your money’ (2015)

In an interview with the Афиша (Afisha) daily, Prusikin stressed that he was involved in a global viral Russian project:

“I have this overarching idea about going global. And I’m glad that we’ve managed to show people who claim that it’s impossible to become popular there because we’re Russians and no one needs us. Russians look at that and realise that they aren’t shit”.

Today, neo-camp is becoming the global language of the Generation Z and the defining style of the era of metamodernism, with its absolute uncertainty, non-binary categories and openness to interpretations. Multimedia projects by Little Big and other young avant-garde musicians, designers, artists, music-video directors and video bloggers (Alexander Gudkov, Tommy Cash, Roma Uvarov, Alina Pyazok, Big Russian Boss and others) are not only a reaction to the colonial look and banter concerning Western stereotypes about Russia but, above all, they are a critique of outdated grandiose Russian patriotism and represent a search for a new visual language and new post-Soviet identity.